Dr Soody Gholami is a research fellow in the School of Creative Arts, Culture and Communication.

My post-doctorate fellowship, titled ‘Decolonising the Curriculum in post-Brexit Britain’, has focused on the ways that democratised and decolonised understandings of English as a discipline can be integrated into the the teaching and curriculum in Higher Education. Throughout the two-year duration of the fellowship, I introduced a series of research interventions, which were supported by teaching practices, surveys and workshops.

In particular, I organised and ran two skill-based workshops, aiming to explore the question: ‘What does a decolonised curriculum look like?’ Both workshops required the participants to critically engage with the colonial context and global power asymmetries that have shaped knowledge production, curricula and selected ‘high-culture’ literature. The two workshops were organized in collaboration with the Research Analyst, Coralie Consigny, whose principal work focuses on exploring societal risks stemming from Artificial Intelligence (AI), which include privacy concerns, biases, and larger systemic threats. The seminars were funded by the Experimental Humanities Collaborative Network.

The first of these task-based workshops was titled ‘Claiming Space in the Digital World: Decolonising the Humanities’ and explored how our connection to ‘space’ (physical or virtual) becomes part of our identity. The seminar began by questioning the ways in which a sense of attachment to a territory/geographical location might be reinforced through country flags, company logos, etc. For instance, British companies such as Tesco or British Airways use the colours of the Union Jack for their business branding. We then explored how this sense of belonging and nationalism would be strengthened or contested in other spaces (digital, political, higher education, etc).

Drawing on Roopika Risam’s New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy (2019), the session then examined the construction of digitised archives and digital literary and cultural record, questioning power relations that could represent and privilege certain cultures and histories and exclude others. This included an extended conversation on the non-neutral and non-democratic digital space and on existing prejudices and biases in big data, algorithms, AI and technological practices.

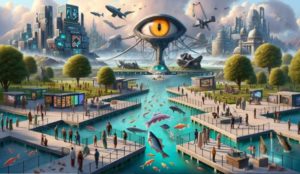

The final task of the workshop engaged participants in thinking about a ‘decolonised Britain’ and a ‘space’ which would be inclusive and accessible to all. We created five categories: ‘Art/Culture’, ‘Infrastructure’, ‘Landscape/Environment’, ‘Universities’ and ‘Living Beings and Interactions’. Coralie and I collected the responses under each category and entered the participants’ textual descriptions into the AI tool Dall.E to visualise a ‘Decolonised Britain’. Once the image was created by Dall.E, participants were asked to critique it and question its biases.

The imaged was generated by Dall.E from the text prompts

Despite the participants’ democratising ideas such as ‘no fences, no doors’; ‘diversity in museums’; ‘no tuition fees’; ‘collaborative learning’; ‘fish as kin’; or ‘accessibility’; it was interesting to see that the AI software centralised and visually centred one of the participants’ suggested terms ‘Sauron-eye watching’. The watching eye determined the rest of space and was positioned in a way to visually and conceptually ‘look down’ on everything else.

The task, which required participants’ critiquing of the AI created image, showcased how participants in higher education can intervene in recognising discriminatory digital practices and in playing an active role in digital knowledge production.

The second workshop, titled ‘Accessible Humanities: Representation as Enablement’, explored different perceptions of disability (medical, cultural, political and legislative) and examined how unequal power relations shaped cultures of disability and disability studies. In particular, certain historical contexts such as colonialism and eugenics were evoked to investigate how imperialist ideologies combined with nationalistic movements and the industrial revolution established a connection between the nation and ‘abled bodies’ for capitalistic purposes. In the seminar, we looked at different political, cultural and material conditions that would negatively and disproportionately impact people in the global south and suggested that disability studies take into account these cultural and historical differences and avoid universalising impairment and disability.

In the context of higher education, the workshop then explored the integration of disability and disability studies into teaching practices and cultural and physical landscape of academic institutions. Through the set tasks, we firstly explored barriers (social, institutional, physical, legal, cultural and technological) that could diminish a disabled person’s full participation in society, particularly in higher education. The seminar then addressed representation of disability, its unrecognised prevalence in literature and culture, as well as prejudices, biases and stigmas around disability.

To engage the participants in different perspectives on disability, Coralie and I set three tasks throughout the workshop. The first activity asked everyone to think of ‘the image of a normal day’. We asked them: what do you need or use to get through your day? Their responses varied from ‘coffee’, ‘glasses’, ‘medication’, ‘cold baths’ to ‘my mobile phone’. The objective of this task was to determine how all of us understood our own bodies and tried to assess and accommodate our needs.

To adopt more inclusive and positive views of disability, the second task encouraged the participants to think about literary and cultural representation of disability. They were first asked to name a film or a book that featured disability. The responses were Rain Man, King Lear, The Untouchables, etc. The participants were then encouraged to discuss how literary representation could question notions of normalcy and be a form of enablement for people with disabilities.

Following this, we looked at two separate cases to examine disability and representation in relation to national identity and belonging: 1. Oscar Pistorius (known as ‘Blade Runner’) 2. The opening ceremony of 2012 London Paralympics. These two specific cases sparked conversations over disability as identity category and its intersection with race, gender and class. Participants explored narratives of nationality and belonging in relation to disability and other forms of identification.

The Tempest’s Miranda is sent by Prospero on a voyage of discovery.

Both workshops encouraged participants to critically engage in the decolonising agenda debates, questioning biases and prejudices that accompany a sense of nationality and belonging in different cultural, digital or political spaces. While the first seminar explored how the connection between territory and narratives of belonging could be contested or strengthened in the digital space, the second workshop examined the relationship between disability and cultural, physical and academic landscape. Thinking in relation to the decolonising agenda, both workshops’ focus on ‘inclusive space’ generated fruitful conversations on democratising teaching practices and curricula.

Dr Gholami is currently writing her book, Unhomely England, due to be published by Routeledge in Dec 2024. She is also writing a chapter entitled ‘Beyond Decolonisation’ for the upcoming book, The Routledge companion to Dangerous Books, due to be published in autumn 2026.

More information: