This post was contributed by Jessica Borge a former PhD student in Birkbeck’s Department of Film, Media and Cultural Studies.

Old adverts for contraceptives fascinate, illuminate, offend, perturb and delight. My own  Doctoral research project, “The London Rubber Company, the Condom and the Pill in 1960s Britain”, unravels obscured marketing practices for commercially traded birth control in the 1960s. As such, I have spent a lot of time looking at contraceptive ads from this period. But using advertising as source materials is a complex business.

Doctoral research project, “The London Rubber Company, the Condom and the Pill in 1960s Britain”, unravels obscured marketing practices for commercially traded birth control in the 1960s. As such, I have spent a lot of time looking at contraceptive ads from this period. But using advertising as source materials is a complex business.

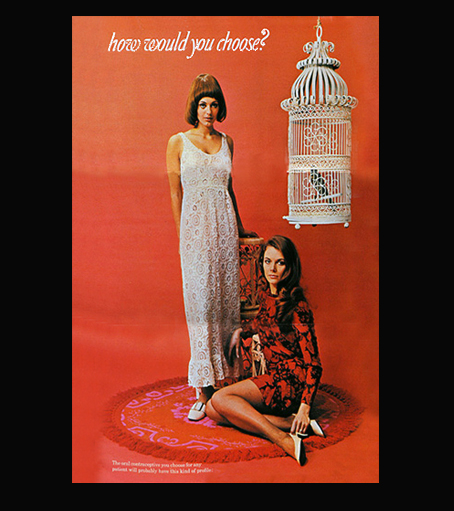

c.1968. Physician’s circular / Searle, ‘Ovulen’. By kind permission of Pfizer. Courtesy of Julia Larden, and the Wellcome Library, London. Photography by J Borge 2014 CC BY 4.0

Unlike non-commercial material from the archives, dusted-off remnants of ad campaigns are possessed of a particular mystique, which might justifiably be described as a sort of ‘faded power’.

At one time, any given advert almost certainly sought to cajole, inform or to inspire action. But, removed from the conditions that engendered their creation and dissemination, impotent old ads no longer sell as powerfully as they might have done in their original setting.

For the researcher, immunity to ‘the sell’ can be an empowering invitation to step in. With the added benefits of historical distance and 21st-century savvy, defunct ads are particularly emasculated by the passing of time, leaving the stage open for involved analysis.

In the case of 1960s contraceptive ads, bonus layers of intrigue expand the potential for fun decoding games beyond the semiotician’s wildest dreams. For one thing, contraceptive products obviously involve sex somewhere along the line. And sex is always interesting. For another, contraceptive manufacturers have long been regarded as, well, ‘a bit dodgy’, which was always part of the challenge of contraceptive communication. An annoying cultural association with wartime prostitution and general grubbiness, for example, marred the image of the condom in post-war Britain. Regulatory barriers also impeded the public use of contraceptive trade names in some advertising (top tip: don’t give your condoms and rubber gloves the same handle – it only makes things worse). For ‘the Pill’, a prescription pharmaceutical contraceptive, print ads were ostensibly intended for the eyes of medics rather than laypeople. Sex – believe it or not – was frequently left out of these ads all together.

But how would you choose? More to the point, how would you be persuaded?

c.1970. Physician’s tri-fold circular / Parke Davis, ‘Orlest’ and ‘Norlestrin’. By kind permission of Pfizer. Courtesy of Julia Larden, and the Wellcome Library, London. Photography by J Borge 2014 CC BY 4.0

Recovery of the advert’s mechanism of persuasion is, for some researchers, the ultimate goal. When this is the reason ads are used as sources, a salvage of probable intentions and effects is – more often than not – conducted by sweeping an imaginary net over the surface, scooping up symbols of interest, and subjecting these to the mill of theory. What or whom is represented here? With whom do these representations resonate? How do such signs govern, or attempt to govern, the roles of those subjects represented, in real life? What does this mean in terms of power and authority? These are all important questions, for sure, and reminiscent of motivational cues known to be employed in creating advertising campaigns in the first place.

But the problem with ads, past and present, is that they are the most available expression of long, labour-intensive processes that are themselves difficult to recover. In portfolios and in archives, as in magazines and on screens, the ad is showcased in isolation. An ad’s workings (i.e., brand history, strategy, rationale, brand objectives, targeting) are concealed, discarded or forgotten. Of course, that is part of the enigma of advertising; it is always very difficult to identify which elements (or combinations of elements) ultimately make an ad effective. Furthermore, many ads that exist in archives are the sole surviving components of bigger, multi-faceted marketing campaigns, minor elements that did not lead campaigns, but rather rode on the coat tails of numerous (unrecorded) promotional activities.

If, as researchers, we primarily regard the surface of a campaign, and consider the visual ad the most choice cut of the marketing mix (primarily because it is more readily available), we risk further obscuring the already illusive apparatus of production and communication. This is regrettable, because production circumstances and processes yield potentially important information. Marketing strategies are conceived not within vacuums, but within complex environments, in which influences and meanings ebb and flow, accrue and evaporate. Like a jigsaw puzzle, it is useful to start with the edges, rather than the middle; in the end, it is surprising how things come together.

With thanks to Alison Payne, Julia Larden, Bryony Merritt, Janet McCabe, Suzannah Biernoff, the Wellcome Library, London, and Pfizer.

Related websites:

About Jessica:

Jessica completed her PhD at Birkbeck in 2017 under the supervision of Janet McCabe and Suzannah Biernoff, with a thesis entitled, “‘Wanting it Both Ways”: The London Rubber Company, the Condom and the Pill, 1915 -1970”. Following this, Jessica undertook a two-year postdoc on the BodyCapital project at the Département d’Histoire des sciences de la Vie et de la Santé, Université de Strasbourg. She holds a visiting fellowship in digital humanities at the School of Advanced Study, and is currently Digital Collections (Scholarship) Manager at King’s College London Archives and Research Collections.

Her monograph, “Protective Practices: A History of the London Rubber Company and the Condom Business” is published by McGill-Queens University Press. More information can be found at the London Rubber Company’s website.

My word to you write well. Scholarly and yet clear. How wonderful!

Oh, also, what an interesting article, thank you!