In May, Birkbeck’s School of Science held ‘Science Saturdays’, a programme of free online talks every Saturday, open to a global audience. In this blog, Maria Pitharouli, Birkbeck and UCL PhD student, gives her account of the talk she attended by Dr Emma Meaburn, Reader in Human Genetics, about DNA and its role in shaping each person’s development, behaviours, and health.

‘What makes us who we are?’, is a question that has occupied Dr Emma Meaburn since she was a teenager and it is what led her towards becoming a Behavioural Geneticist, as she explained in her recent talk.

Behavioural genetics is focused on the influence of nature (our genes) and nurture (the environment we are exposed to during our lives) on the differences we can observe or measure amongst people. But to understand the effect of nature and nurture we need to understand first what DNA is and how big a role it plays in our day-to-day lives.

The human genome is contained in the nucleus of every cell in our bodies, and it is the complete set of genetic instructions: a sequence of approximately 3 billion of the DNA bases adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). Each cell has two copies of these genetic instructions, one inherited from the mother and one from the father. Most of the genetic code is identical amongst humans and follows a specific order. Dr Meaburn talked about why this similarity in the genetic code between people is so important; the sequence of A’s, C’s, G’s and T’s acts as a guide for our cells so they can function properly and create all the components needed to sustain life.

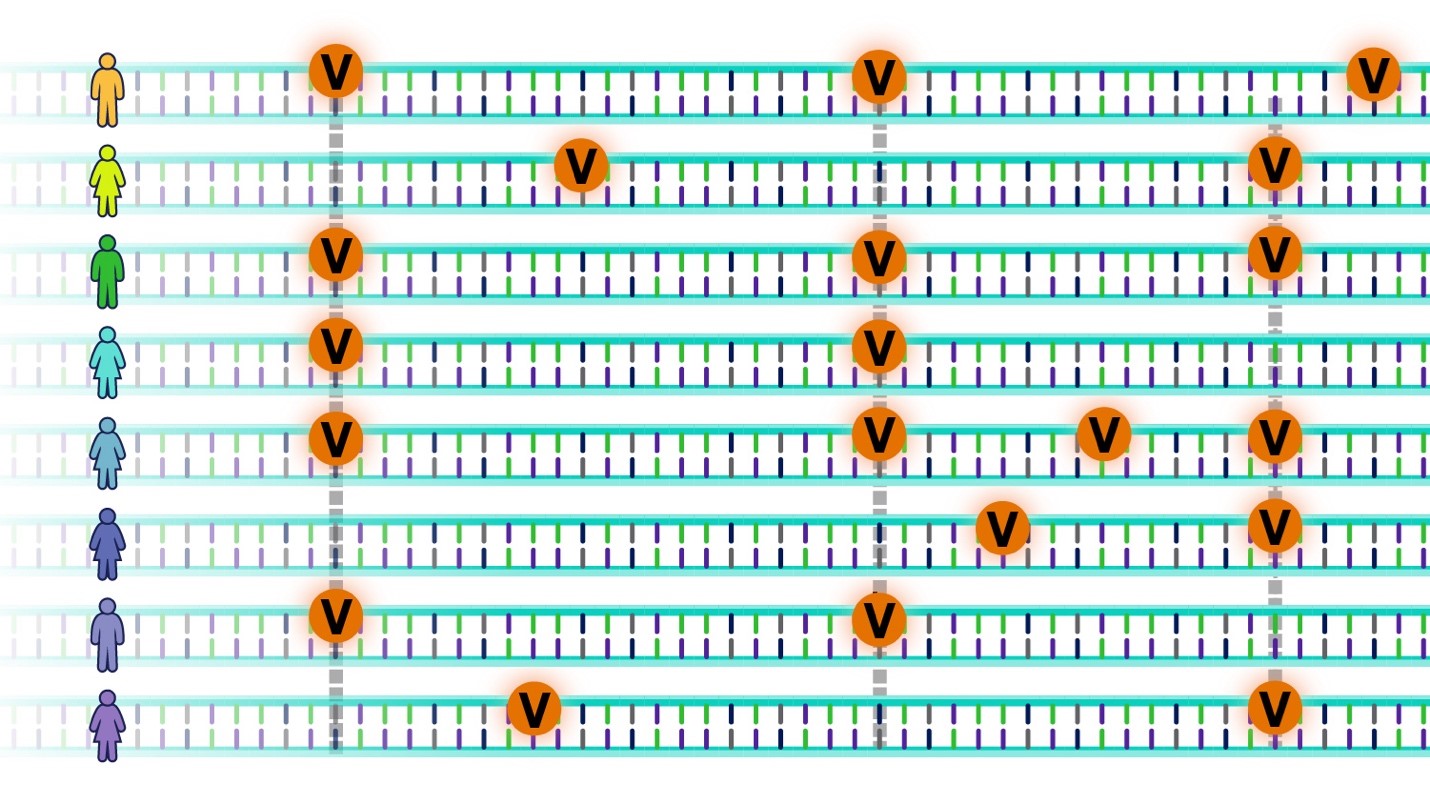

Image 1. The letter “V” indicates the genetic variants scattered throughout the human genome. Source: Polygenic Risk Scores (genome.gov)

However, despite this similarity there are parts of the DNA code that differ between people, called genetic variants (image 1), and they are scattered throughout the human genome. These DNA differences are what really interests Dr Meaburn as they might explain some of the variation in how we think, feel, and act, or why some of us develop health conditions. In the talk, Dr Meaburn described how behavioural genetic research has shown that there isn’t a single gene (or DNA difference) that can explain differences in human intelligence, personality, or susceptibly to mental health conditions such as depression. These complex (or multifactorial) traits and disorders are the result of lots (and lots!) of common genetic variants in combination with our different life experiences.

The talk then described a method called genome-wide association studies (or ‘GWAS’) that have been hugely successful in identifying the specific DNA differences that relate to complex human behaviours and traits. The GWAS approach requires very large numbers of research participants – typically tens of thousands of people – who donate both DNA and information about their health and behaviours. Interestingly, while GWAS have identified many of the genetic variants that contribute to differences in human health and behaviour, Dr Meaburn emphasised that each of the variants found explains just a tiny amount of the differences we see amongst people. As a result, we now know that complex mental health conditions such as depression are polygenic; any single genetic variant does not cause the disorder, rather many of them together can increase or decrease one’s predisposition to depression.

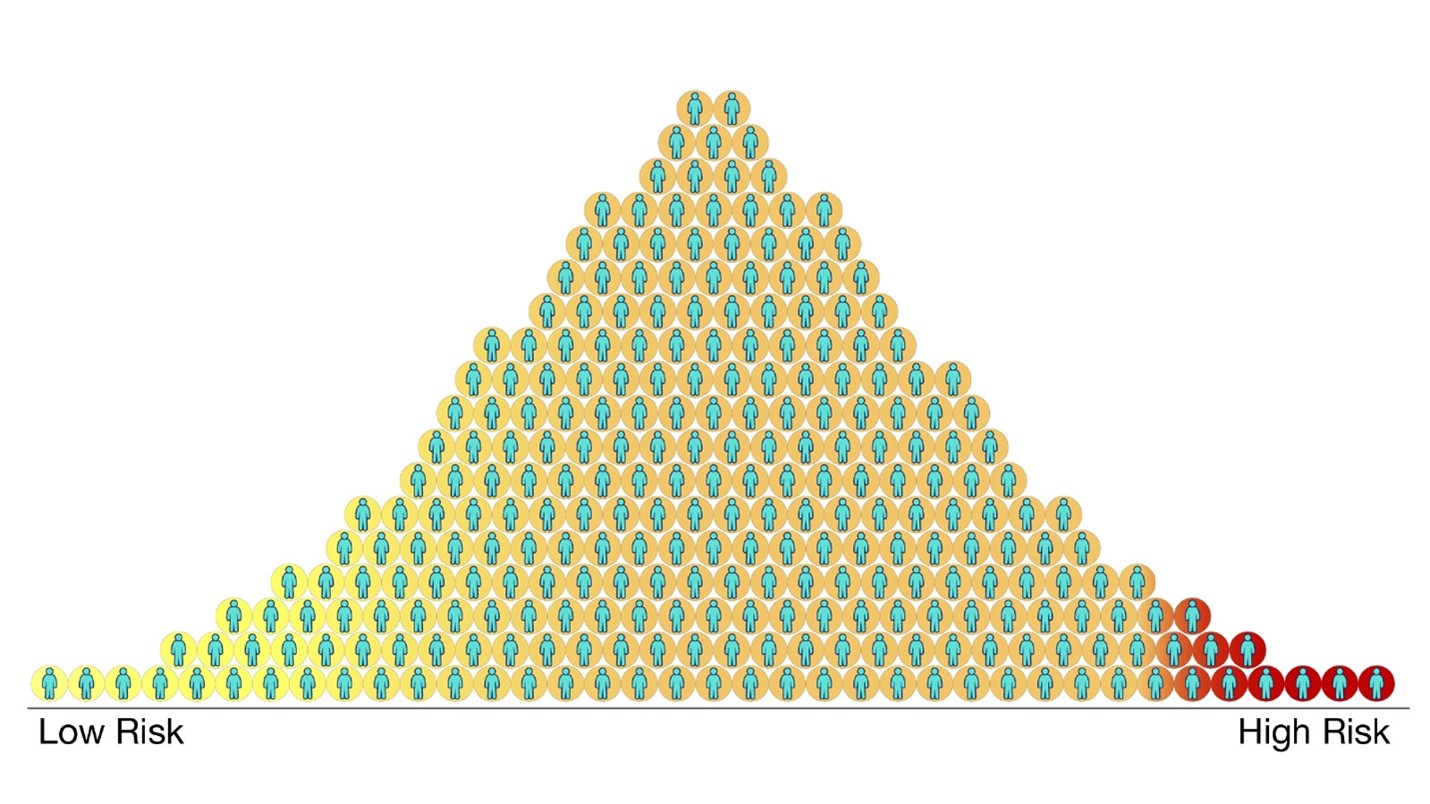

Dr Meaburn went on to describe how polygenic scores – the sum of the effect of all genetic variants that can either increase or decrease risk to develop a disorder – could potentially be useful for identifying individuals more (or less) susceptible to a wide range of human behaviours or health outcomes (image 2). However, it is important to keep in mind that polygenic scores will never be a ‘crystal ball’, as while DNA differences are important, we know that our environment and life experiences matter too.

Image 2. Polygenic scores can help us identify someone’s genetic likelihood to develop a specific disorder or trait. Source: Polygenic Risk Scores (genome.gov)

The take home message from the talk is that the DNA sequence you have inherited from your parents is an important piece of the puzzle in explaining what makes you, you. Your own unique DNA code plays a role in shaping your development and nudging your health in certain directions. In the last ten years GWAS research has shown us which DNA variants are important, and the real challenge for the next ten years is understanding how they lead to differences between us in how our brains work, and how we interact with others and the wider world around us.

Further Information