Eva Menger, freelance copywriter and MA Contemporary Literature & Culture student, reports on Birkbeck’s recent Documenting Refugees event, which combined Kate Stanworth’s photography exhibition Where We Are Now with a screening of Orban Wallace’s documentary Another News Story.

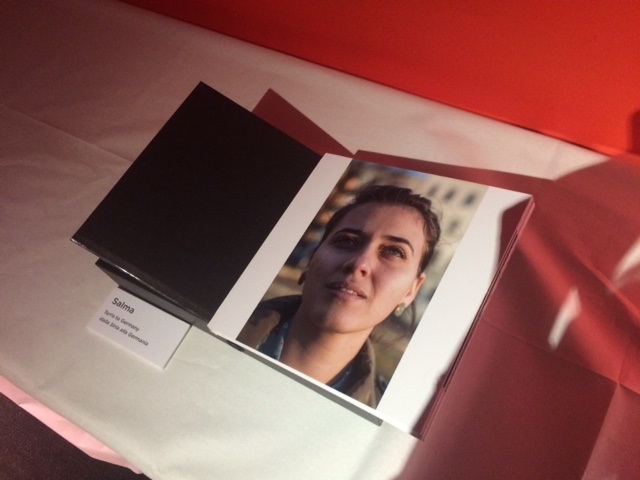

Kate Stanworth’s photo of Salma, who travelled from Syria to Germany.

Wednesday 20 June marked World Refugee Day, an event through which the UN seeks to show governments the importance of collaboration as a means to accommodate forced migrants all over the world. With the global number of refugees being at an all-time high, this year stood for commemorating their strength, courage and perseverance. In light of this message, Birkbeck lecturer Agnes Woolley hosted ‘Documenting Refugees’, a thoughtful evening discussing the way in which refugees are represented both in the arts and media.

The event combined Kate Stanworth’s photography exhibition Where We Are Now with a screening of Orban Wallace’s documentary Another News Story, both of which reveal an intimate portrayal of refugees and their stories. For Stanworth, the focus lies on personal narratives and the psychological survival techniques used by refugees during the most difficult times. In addition, her portraits reveal how reaching the final destination (typically Germany or the UK) is still very much the beginning of the long journey forced immigrants have got ahead of them.

A similar idea is conveyed in Another News Story, where Wallace and his team follow both the refugees and journalists portraying them on their challenging journey across Europe. While the documentary offers an excellent balance of mixed narratives, the character that stands out most is Syrian mother Mahasen Nassif. Not only is her excellent English, positivity and strength while travelling alone completely overwhelming; her story also shows how getting to Germany is not where the refugee experience ends. When, in the panel discussion afterwards, director Wallace is asked about her he admits that she is finding it challenging to be living a slow-moving life in a remote town in Germany, endlessly waiting for documentation. A side of the story we hear a lot less often.

What is also special about the documentary is that it was shot without any kind of plan, with the main characters being simply those they kept running into. Finding a repertoire of narratives was therefore an entirely natural process, Wallace explains. And ultimately this has led to a uniquely nuanced documentation of a phenomenon that is predominantly being told through the biased and sensation seeking media. The documentary title already hints at this, but insights given by Bruno, a Belgian journalist and recurring character in the film, make it all the more evident: the news is wherever the media is – be that refugee camps at the Hungarian border or the Venice film festival.

‘Another News Story’ teaser

Both during the screening and discussion afterwards, the main issue with documenting refugees seems to be the fact that it is ongoing. As Ahmad al-Rahsid, a forced migration researcher at SOAS who fled from Aleppo in late 2012 comments, the Syrian conflict is considered by critics to be one of the most documented conflicts of humanitarian history, yet it took the picture of one little boy to finally cause a shift in political and public responses. People don’t typically respond to just another news story, and with crises without a beginning or end that is a very big problem. The refugee crisis didn’t start nor end in 2015; it is a long-term humanitarian issue that needs as much attention now as it did three years ago. Events like this are needed to help us realise that.