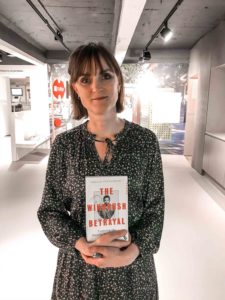

Zeljka Oparnica, PhD student in the Department of History, reports on journalist Amelia Gentleman’s talk about the Windrush Scandal that took place as part of the Department of History, Classics and Archaeology’s Discover the Past lecture series that welcomes Birkbeck students, alumni and guests.

Amelia Gentleman’s reportages in the past two years covered a series of immigration issues that became known as The Windrush scandal. In this talk, she covered the background of both her reporting and the results it had provoked.

Professor Jan Rueger, Head of the Department of History, Classics and Archaeology Department greeted the audience and introduced the speaker and her book, stressing an important historians’ credo: “People’s voices matter, individual lives matter, and persistent research and adept covering of injustice can make a difference.” Amelia Gentleman began by reflecting on her background in history. That was a great introduction to the talk that followed the storylines of individuals leading to the discovery of a systematic fallacy, showcasing the background of “big history.”

What led to the series of reportages was a single case which came to Gentlemen through an NGO in November 2017. It was a story about a woman who came to the United Kingdom in her early childhood and was detained and about to be deported to Jamaica at the age of 61. For about two years prior to her detention, she had been receiving letters from the Home Office warning her about her illegal status. What at first glance seemed to be an oversight by the Home Office, turned out to be just the first among many isolated cases. The day when the article was printed in the Guardian, Gentleman received a call from the son of a man in a similar situation facing deportation. The individual cases started to line up and it became evident there was more to the series of what seemed like lone, disturbing cases. Her emphatical but sober writing, followed by amazing photo portraits, incited readers’ reactions and brought the well-needed attention.

Beyond talking to a number of affected individuals, Gentleman also referred to immigration lawyers, law centres, and PMs from areas with high immigration rates. As the stories received ever more publicity and caused a public uproar, the Home Office reacted to individual cases, and ministers offered half-hearted apologies. There was a rush to resolve the most prominent cases, and it was difficult for all the people invested in helping to connect the dots.

After months of research, Amelia Gentleman came to a true historical revelation. Behind the dozens of comprehensive individual reportages were around 500,000 cases of undocumented people who were born in the Commonwealth countries and came legally, as imperial citizens, to the United Kingdom in the period between two Immigration Acts, namely 1948 and 1973. The lack of personal documents, such as passports, went hand in hand with what Gentleman called “the general British papers distrust.” Namely, even today 17% of British citizens do not possess passports, and in the previous decades, the number was much higher. It became apparent that the trigger was the so-called Hostile Environment, the Tory anti-immigration policies that came to power in the early 2010s. It became apparent how the citizenship of thousands of people depended on the unjust context of the present.

The stories reached their peak in 2018, overlapping with the seventieth anniversary of the arrival of the ship Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks in Essex. Since those affected by the new Hostile Environment policies were the descendants of the people who arrived in the same period, and it seemed like an appropriate name for the scandal Gentleman’s reportages.

However, Gentleman still feels bitter-sweet about the outcomes of her work. As a direct result of the stories’ publication, Home Secretary Amber Rudd resigned in April 2018 and a public promise was given to all affected that they could claim compensation from 200 to 572 million pounds. Up until today, over eight thousand people affected by the scandal have been granted citizenship or papers that confirm their full legal status. The number of detainees in deportation camps has also decreased. However, only 32 people have received some compensation, and many of those who have a right to compensation have either died or are very old. The Hostile Environment policies have not been repealed nor debated. With this sobering overview, Amelia Gentleman ended her talk by underlining that the list of tasks is long. For both journalists and historians.

In the well-established Birkbeck tradition, the talk sparked a comprehensive discussion that lasted for another hour.