Lynsey Ford, an alumna of Birkbeck, discusses an Arts Week event looking at architecture and pedestrians with photographer Chris Dorley Brown.

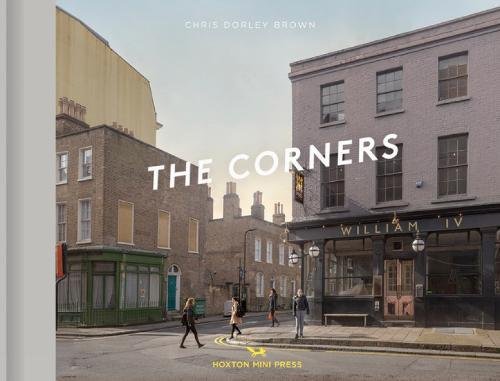

Documentary photographer and filmmaker Chris Dorley-Brown visited Birkbeck Arts Week at The School of Arts on Friday 18 May to discuss his 30-year career as a freelancer. The talk coincided with the release of his new publication entitled The Corners by Hoxton Mini Press, which examines his photography between 2009-2017 across East London street corners, industrial buildings, landscapes and architecture.

Initially trained as a silkscreen printer and print finisher, Chris branched out as a freelancer in 1984. Living and working in the East End for over 20 years, Chris began his media career working as a camera assistant for Red Saunders studio. His comprehensive slide show of his street photography at Birkbeck discussed his initial work building a photographic archive with the London Borough of Hackney.

Chris quickly started to develop his own digital techniques to create narratives; working with multiple exposures taken over an hour, Chris’s images have used around 100 shots taken at different times. These shots have been constructed to resemble one definitive image creating a surreal, dreamlike narrative of the urban landscape. The stillness, composition and colour of all his images adopt the look and feel of an oil painting. Notable shots include a police evacuation where the police sealed off the streets after the discovery of a bomb from World War 2. A boy is seen in disbelief holding an apple near the sealed off area, whilst a faceless young lady, oblivious to potential danger, cannot help but investigate, walking towards the tape. Other images perfectly capture the cynicism of city life, from the street voyeur, a homeless man, who emerges from the hidden corner of a local high street, facing off at an unseen Chris behind the lens. Old pedestrians ‘collide’ with the younger generation of cyclists across the traffic junction emphasising at the inevitable ‘changing face’ of the landscape. Chris also revisited his photography capturing ‘Drivers in the 1980s’. The slideshow perfectly expressed the conflicting emotions of Londoners, from a spaced-out businessman alone in his thoughts inside a red double-decker bus, to the visibly frustrated faces of motorists, caught between shots and the intermittent traffic lights during rush hour.

The talk provided a nostalgic look at London life and Dorley-Brown’s work is a great testimony to a skilled media professional who perfectly captures the history and architecture of the East End.

Further material from Chris’s career can be obtained through the public collections of The Museum of London and The George Eastman Museums.