Fleur Kaminska, MA Museum Cultures student at Birkbeck shares insights from the Arts Week event that explored rethinking history through collage.

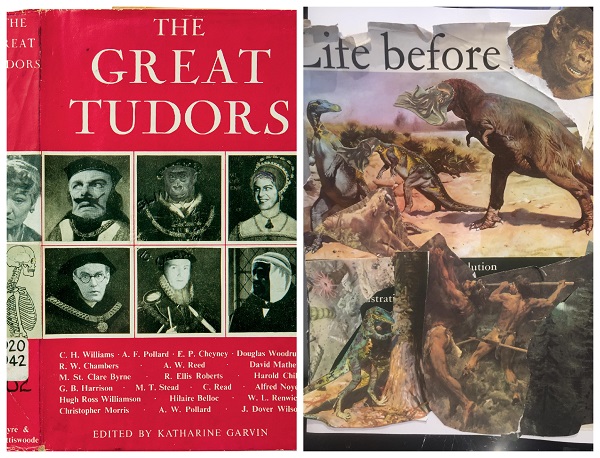

The left-hand side is a doctored cover by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, and the right-hand side is Fleur’s attempt at a doctored cover, produced on the evening.

Adam Smyth (author and professor of English Literature at Oxford University) and Gill Partington (academic and writer, and the current the Munby Fellow at Cambridge University) took the attendees of last Tuesday evening’s Arts Week event on a cheerful journey through the creative reimagining of the pages of a book, dismantling the idea that ‘cutting up’ is a destructive act and reframing pages as material for endless possibilities of creative expression. Both conveying an interest in the intersection between the physical book and literary writing, Adam and Gill introduced collage as a creative, rather than destructive act –an act potentially of protest that is open for experimentation to anyone (including, at the end of the session, us!).

Collage as self-portrait

Starting with an early form of collage, Adam spoke about a commonplace book made by John Gibson in the 17th Century. Gibson was a royalist who used his time in prison to produce a vast book, weaving together poetry, literary references, images, anagrams and political details to construct almost a distanced self-portrait of a royalist sensibility. The pages produced are incredibly varied and interesting on many levels. Often also open to manipulation through pictures stuck in as flaps layering over one another, or through the scattered presentation of the material, the pages invite the readers eye to encounter images and pieces of text in different orders, creating different associations. Later on, Adam also read to us from his book 13th of March 1911, in which he collected information about events from the date of his grandfather’s birth to create a meandering portrait of the day.

Collage as criticism

Moving forward in time, Gill Partington talked us through the work of wonderful and, at the time, controversial, Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, who spent the early 1960s visiting libraries, taking books out, doctoring them in their shared bedsit, and then returning them to the libraries for unsuspecting readers to encounter. The pair, who reworked the covers, and sometimes the blurb and whole sections of the books, blurred genres into one another to create ludicrous and joyful mismatches.

The way this was done, mixing high and low culture, fiction and non-fiction, poked fun at the books and their readers, but also more seriously at the status of the library as an institution. The library, especially at this time, served as a gatekeeper of knowledge, and a place in which good citizens enacted their duties of not only self-improvement but also a demonstration of their commitment to the accepted histories and categories of experience presented on the shelves. In this way, the library was at odds with Orton and Halliwell’s lives together as a gay couple. In the end both were caught and sentenced to six months in prison, a much harsher sentence than you’d expect, but most likely reflecting the higher taboo of their lives, rather than the damage to public property. By destabilising norms and expectations in their personal lives as well as in their library collaging, Orton and Halliwell were perceived as a threat to society at the time, but are now celebrated as creative activists.

Collage for beginners

For the final section of the evening the scissors and glue were passed to us, and we had a go at doctoring text, dust jackets and creating whatever the hell we wanted from a selection of books and print materials. With the whole room getting stuck in and experimenting (or, in my case at least, regressing to childhood and throwing all notions of sense out of the window) some fantastic work was created. Ultimately, we all learned to get over our nervousness about cutting into books, creating incongruous scenes, and blurring the boundaries between printed page and meaning.