This post was contributed by Dr Ben Winyard, digital publications officer at Birkbeck, University of London

Why do we blush and what does blushing signify? Is blushing simply an automatic, physiological response with roots in our animal nature and evolutionary development, or can we interpret blushes to gain an insight into what is happening below the surface in a person’s mind? And which emotions does a blush betray – shame, modesty, anger, desire?

Why do we blush and what does blushing signify? Is blushing simply an automatic, physiological response with roots in our animal nature and evolutionary development, or can we interpret blushes to gain an insight into what is happening below the surface in a person’s mind? And which emotions does a blush betray – shame, modesty, anger, desire?

These were the key questions explored by Dr Paul White of the University of Cambridge in his fascinating paper ‘Modelling the Blush’ at the ‘Arts and Feeling in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture’ conference held at Birkbeck from 16–18th July 2015.

The conference brought together over one hundred scholars to consider how feeling was stimulated, modified and expressed via art and literature in the nineteenth century and how the Victorians themselves understand their feelings. Dr White is a leading figure in digital humanities and the history of emotion and is Editor and Research Associate on the Darwin Correspondence Project, which has made over 7,500 of Darwin’s letters freely available online.

Bell and Darwin: A physiological view of the blush

White began by sketching how emotion became an object of study in the nineteenth century, particularly within the burgeoning field of physio-psychology, the forerunner of many modern scientific disciplines such as neuropsychology.

In the nineteenth century, the new experimental physiology of scientists such as Charles Bell sought to understand the blush in terms of the central nervous system and the dilation of blood vessels. In his Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting (1806), Bell observes that the face contains ‘a peculiar provision of nerves, which are entwined around the vessels, and give them a susceptibility corresponding with the passions of the mind […]. Hence the sudden blush, and rapid change of colour upon slight emotions.’

Charles Darwin was similarly fascinated by human emotions, particularly their evolutionary and adaptive functions, and in 1872 he published The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, which is lesser known than his more famous works but equally engaged with the descent of humans from animals.

Charles Darwin was similarly fascinated by human emotions, particularly their evolutionary and adaptive functions, and in 1872 he published The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, which is lesser known than his more famous works but equally engaged with the descent of humans from animals.

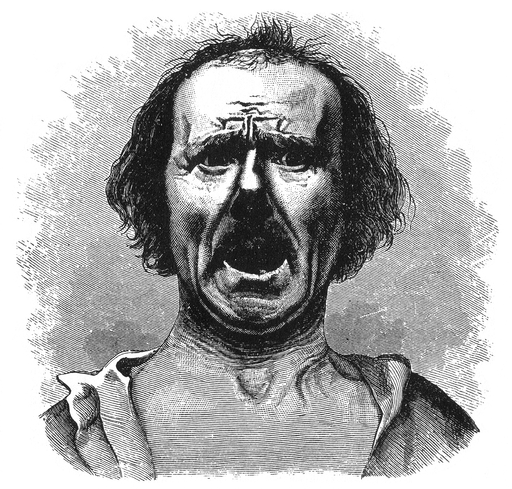

Darwin observed and noted the physiological expression of emotions in his own children and began collecting and commissioning pictures and photographs of infants, children, animals and people interred in asylums in an attempt to analyse the universal facial expressions and bodily gestures of particular emotions.

For Darwin, the blush is the ‘purest’ physiological response, an involuntary, reflex action of the nervous and circulatory systems whereby increased blood flow brings a red tinge to the cheek and elsewhere. Darwin was interested in the animal origins of facial gestures and he describes blushing as a uniquely human, but relatively late evolutionary development, firmly aligned with sexual desire and sexual selection – hence its prevalence in the (amorous) young.

The blush as a vehicle of narrative

Conversely, though, the blush has a narratological function and it operates as a literary device and as a vehicle of narrative, which raises it above a purely physiological understanding.

For centuries, the blush has been understood as an authentic external expression or register of inner feeling, including innocence and purity of heart. For all this, it remains ambiguous. Throughout the eighteenth century, it was the novel that provided the main vehicle for exploring the blush’s multiple meanings. White focused on a fascinating moment in chapter 15 of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813) when Elizabeth Bennet observes an unexpected meeting between Mr Wickham and Mr Darcy:

Elizabeth, happening to see the countenance of both as they looked at each other, was all astonishment at the effect of the meeting. Both changed colour; one looked white, the other red. Mr. Wickham, after a few moments, touched his hat – a salutation which Mr. Darcy just deigned to return. What could be the meaning of it? – It was impossible to imagine; it was impossible not to long to know.

Here in miniature, then, is the mystery of the blush and the ways in which it spurs us to narratological analysis and speculation. For Austen, the blush is a mark of sensibility, of finer feeling and the ability to respond sympathetically to complex emotional and aesthetics influences, and reading it accurately enables and registers an empathetic identification that is key to social intercourse and human bonds.

Sensibility was a hugely influential idea in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century and White went on to consider how skin is a register of sensibility in portraiture of the time.

Narration vs physiology

The Victorian novelist George Eliot was immersed in the latest scientific research of her day, including the evolutionary theories of Darwin, but in her lesser-known historical novel Romola (1862–63) she explores the blush in narratological terms. Set in Renaissance Florence, the novel follows the titular hero as she navigates the intellectual, cultural, religious and political tumults of fifteenth-century Italy.

Eliot focuses on the unhappy marriage between Romola and Tito, a duplicitous, bigamous political manoeuver who betrays Romola’s godfather to his death and fathers two children with a secret wife. In chapter nine, Tito discovers that his adoptive father has been enslaved, but, after comparing his filial duties to his youthful ambitions, he decides against a rescue attempt. However, as he tries to inwardly assert ‘that his father was dead, or that at least search was hopeless’, Tito is unable to repress his ‘inward shame’, which shows in ‘blushes’.

Eliot thus converts the instinctive blush mechanism into narrative; although Tito is unobserved by any character in the novel, the narrator and the reader ‘see’ his moral failings betrayed by his physiological response. For Darwin, though, whatever feelings or narratological meanings are attached to the blush by humans are immaterial and he prioritises the physiological response.

Dr White finished with the fascinating observation that, although the mechanisms of the blush are understood by contemporary scientists, there is still debate on the question of why we blush: you can Google ‘Why do we blush?’ to get a taste of the lively discussions that are still ongoing.

Find out more