By Russell Banfield

Where does the character end and the actor begin? That’s the question behind Doozy, an essay film by Richard Squires that weaves academic commentary, animated dramatizations, and childhood recollections to explore the life and career of Paul Lynde, a closeted gay actor who voiced some of Hanna-Barbera’s best-loved villains, but who struggled with alcoholism, typecasting, and the constant tension between his public life as a popular comedian and his private life as a closeted homosexual. Each of the characters he voiced regularly dressed up in drag, were always humiliated at the end, and all had a snarky, camp voice, sniggering laughter, and fey mannerisms. Was it simply coincidence that Hanna-Barbera cast Lynde as these villains?

The term “doozy” means something extraordinary or unusual but often placed in a negative context. It could describe Paul Lynde himself: he found fame as a recurring character in the TV series Bewitched and as the center square in the US game show Hollywood Squares, where he appeared in over 700 episodes, which Squires faithfully recreates the set design to place his contributors. Lynde also voiced Sylvester Sneekly aka The Hooded Claw in The Perils of Penelope Pitstop, Mildew Wolf in Cattanooga Cats, Claude Pertwee in Where’s Huddles? and Templeton the rat in the studio’s feature length animated movie Charlotte’s Web. Perhaps because of his closeted sexuality, fame didn’t come easy to Lynde who soon become an alcoholic, and a nasty one at that, venting his anger and frustration on anyone at hand, too often in public.

Doozy is no biopic of Lynde though, more a mediation on cartoon villainy and queer cinematic representation. Squires uses the testimony of an old high school friend of Lynde to flesh out Lynde’s backstory growing up in Mount Vernon, Ohio but the woman’s recollections are more interesting for what she omits rather than painting a fuller picture of Lynde. We are told that he was overweight, was the class clown, liked to act and dress up, and seemed enamored by a high-school sweetheart. What is completely absent is his homosexuality. It is as if the Mount Vernon sequences in Doozy act as the living rooms of Middle America in the 1960s and 1970s that embraced Lynde but simply refused to acknowledge or were blind to his sexuality.

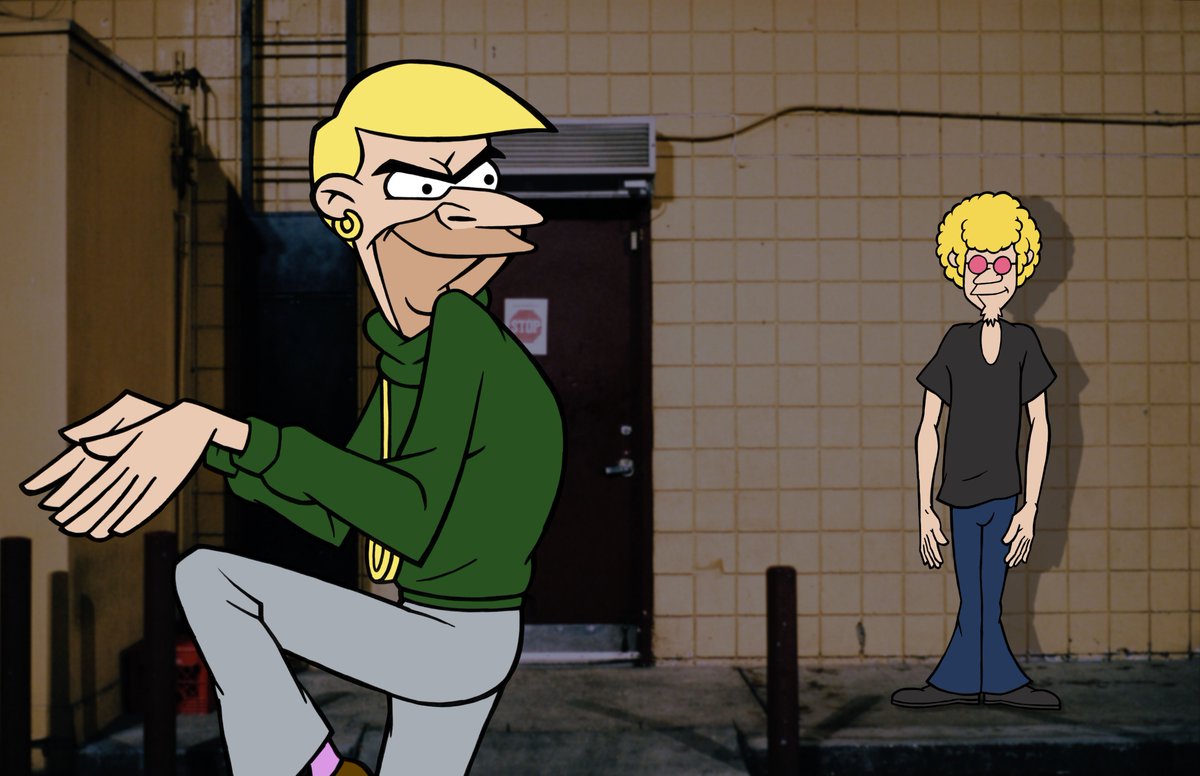

In contrast, the “Clovis, the cartoon villain” animated sequences, set in Los Angeles, depicts a decadent, sleazy, and anonymous world where a closeted gay actor could hide in plain sight, if only at night. Squires uses Clovis as a stand-in for Lynde to re-enact several alleged incidents from Lynde’s life in Hollywood to give some sense of the complexity of the life he led, the duality, the masking, and the criminality of being a closeted gay man in the 1960s and 1970s, and the humour he used to navigate through it. The Clovis sequences also stand in for the Hanna-Barbera cartoons themselves; copyright issues meant that Squires was unable to show any footage of the cartoons that Lynde voiced so Doozy offers the strange experience of watching other people watch these cartoons with only the soundtrack playing. For a film that emphasizes voice as signaling otherness, that is hardly a deal breaker, but the Clovis scenes help to flesh out the film’s central argument over representations of cartoon villainy and hysterical masculinity.

So, was Lynde’s sexuality key to his casting in these roles? Doozy certainly thinks so, arguing that Lynde’s camp, hysterical delivery, his acerbic, snide retorts, and is own coded sexuality all pointed to his otherness. Yet Lynde also brought his own sense of humiliation, anger, and fragility to his roles that make his characters, The Hooded Claw and Mildew Wolf in particular, seem more sympathetic than they might otherwise have been. Claude Pertwee is more problematic, “an unhappy, embittered old queen” as contributor John Airlie puts it; sneering, nasty, supercilious, and mean-spirited, the audience is primed to laugh at rather than with Claude’s humiliations. More problematic is that the Pertwee character seems closest to Paul Lynde’s real life persona. Thus, if the characterization of Claude Pertwee is regressive then what are we to make of Lynde himself? Squires remains sympathetic but can only achieve this by refusing to re-enact Lynde’s more outrageous behaviour, keenly aware to avoid such negative queer representation.

The final irony is that a drunken Lynde acted more the cartoon villain than any of his characters ever did. Perhaps this explains why Lynde has become a footnote in American popular culture instead of being embraced as a gay icon of sorts, a trailblazer who found fame and success in a period marked by discrimination. Even more damning is that Mount Vernon has seemingly fallen out of love with Lynde, replacing the welcome sign that proudly acclaimed “the hometown of Paul Lynde” with one that celebrates Daniel Decatur Emmett, author of “Dixie”, the song that became a Confederate anthem during the Civil War. Doozy attempts to reverse this trend and rescue Lynde from obscurity, and whilst it struggles to get a grip on an interesting, difficult, and problematic man, the film does succeed as a celebration of his incredible voice and as another important chapter in the hidden queer history of Hollywood.