Delighted to present the second in our series of blogposts by staff and students of the department exploring the urgency and complexity of museums’ and monuments’ involvement in the legacy of slavery and colonialism. The first post, featuring Annie Coombes, can be read again here.

The latest one, which you can read here in Birkbeck Comments, is by Dr Sarah Thomas, Lecturer in the department, and Director of the Centre for Museum Cultures. Sarah reflects on an exhibition that changed her mind in 1990s Sydney, and talks about how her research on the important of wealth derived from slavery in the early development of the public art museum in the UK. (Art) history matters, she argues, allowing us to get to grips with unfinished colonial business, then and now. Do have a read.

Colonial Afterlives exhibition catalogue cover. Image by Christian Thompson, Trinity III, from the Polari series, 2014. Christian Thompson is represented by Sarah Scout Presents (Melbourne) and Michael Reid Gallery (Sydney and Berlin).

Professor Steve Edwards, historian of photograhy in the department, contributes this fascinating field note on a recent discovery and how it inadvertently opens up another angle on current debates. Over to Steve:

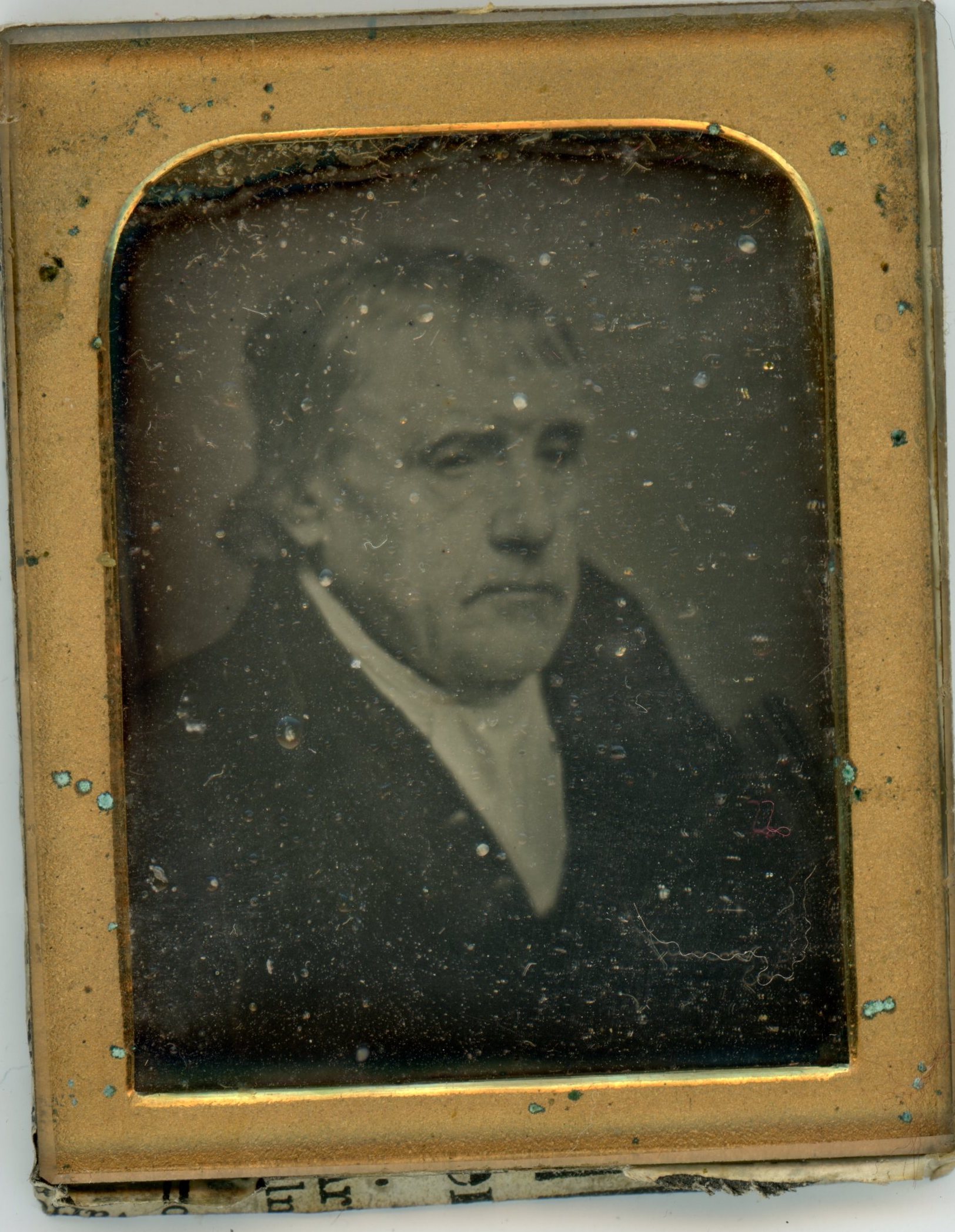

For some time, I’ve been working on a history of the daguerreotype trade in Britain between 1839 and 1855. Recently, I decided to clean an interesting batch of these objects, which included a pair of betrothal portraits and a portrait of a young officer from regiment of the East India Company. To clean a daguerreotype, you have to remove the plate, mat and glass from the case and scrap away the paper seals that bind these elements. This enables a restorer to remove dust and moisture from the plate and clean the aged Victorian glass. You then rebind the cleaned components with archive-grade tape and insert the package back into its case. Among the batch there was also a small and unremarkable portrait of a man.

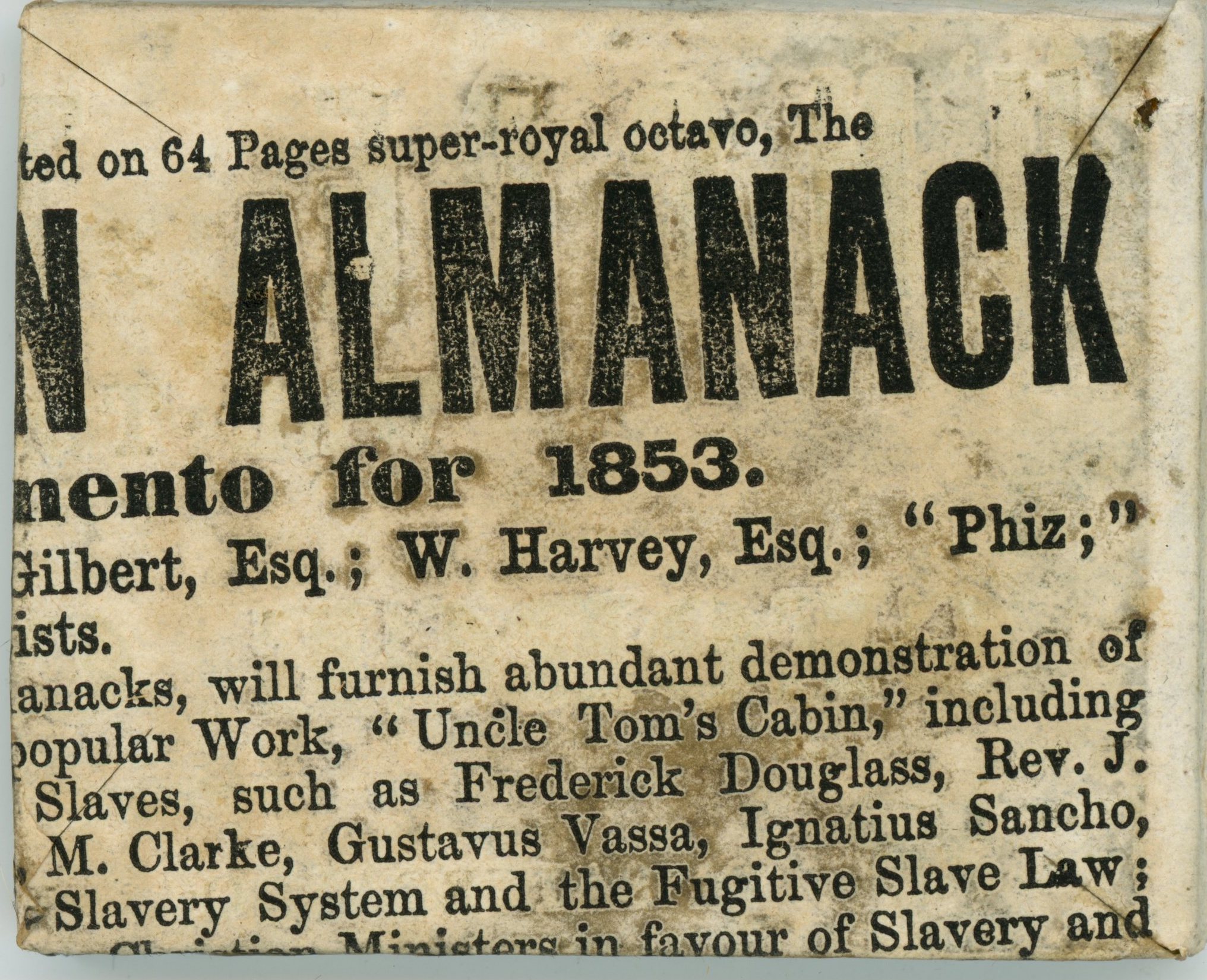

It struck me as an insignificant image, but it was getting late and I realised I wouldn’t be able to do anything else, so I decided to clean this one too. When I removed the plate from the case, I found that it was bound with an anti-slavery flyer. You never know what you might find when dealing with the archive!

Over the last couple of weeks we have heard quite a few people in the media saying it is wrong to judge people from the past by our standards. This argument is mobilised against #BlackLivesMatter, because, we are told, everyone at the time accepted chattel slavery. It simply isn’t true. Religious dissenters, particularly Quakers, often opposed slavery, boycotting coffee and sugar because of the association of these commodities with the plantation economy. Some historians have argued this boycott gave rise to the British habit of tea drinking. Audiences packed lecture halls to hear freed slaves speak about their experiences. Political radicals also opposed slavery and Lancashire factory workers frequently referred to themselves as ‘wage slaves’ making the connection between their own conditions and human bondage in the United States. To call oneself a wage slave was also a way of exposing the hypocrisy of those factory masters who condemned slavery in the Americas, but employed adult workers and children in appalling conditions. The photographers who made this ordinary daguerreotype portrait must have had the leaflet to hand in the studio. It is another little sign that opposition to slavery was circulating in Britain before the Civil War. There have always been voices raised against human bondage, so no, slavery wasn’t universally accepted whatever some media pundits might claim.

**

Continuing on the theme of my colleagues’ timely and pertinent research… Professor Kate Retford has recorded a wonderful podcast for the rich series British Art Talks, hosted by the Paul Mellon Centre. In it, she discusses the persistent tendency in the 20th century and up to today for country houses to be marketed with an emphasis on their status as private homes – a tendency that’s both effective and politically freighted.

Another podcast, by Professor Mark Crinson, made for this year’s online Arts Weeks, is called ‘The Smoke’. Mark offers a close reading of an engraving (which you can look at on the same link as you listen) showing an aerial view of a section of nineteenth-century Manchester, the industrial city par excellence, complete with dense air pollution, which in those days was a lot more visible than it is now, if not much more deadly.

Finally, a reminder to join us for the end of term party next Friday 10 July at 7pm – quiz time! Link to come.