One last post on the History of Art department blog before the summer break (or in the midst of the summer break for some). Really delighted to be able to pass the microphone, as it were, to two students.

Gaynor Tutani is a student on the PG Diploma in Museum Cultures. She’s written an thought-provoking and deeply felt piece for us relating the impact the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement has had on her, and addressing the changes she wants to see in the staffing and policies of museums. In her piece, which you can read in full on Birkbeck Comments here, she writes:

‘As a keen student of history and a cultural facilitator, I believe that museums and other cultural institutions can make lasting contributions and be an example of the change we need, via a true engagement with our society. One that does more than tick the boxes of inclusion and diversity, but actually acknowledges our society’s unique cultural fabric and how it came about. We have to honestly discuss controversial topics such as racism and its intricate connection to our lives. I believe that art can inspire and change people’s perspectives and understanding of their world. Consequently, museums and curators should do more to address difficult issues within their curation and programming.’

Gaynor’s post is the final in a series published on Birkbeck Comments and on this blog over the last few weeks by academics and students from the department on the intersections between racism, slavery’s legacies, decolonisation, protest, memorialisation, statues and visual arts institutions. Here they all are in one place:

Annie Coombes, Making Monuments Matter

Sarah Thomas, (Art) History Matters

Gabriel Burne, To Lie About History: Statues and the British Slave Trade

Gaynor Tutani, The Unfortunate Persistence of Being

Annie Coombes, Decolonizing the Curriculum: “Benin in the World”

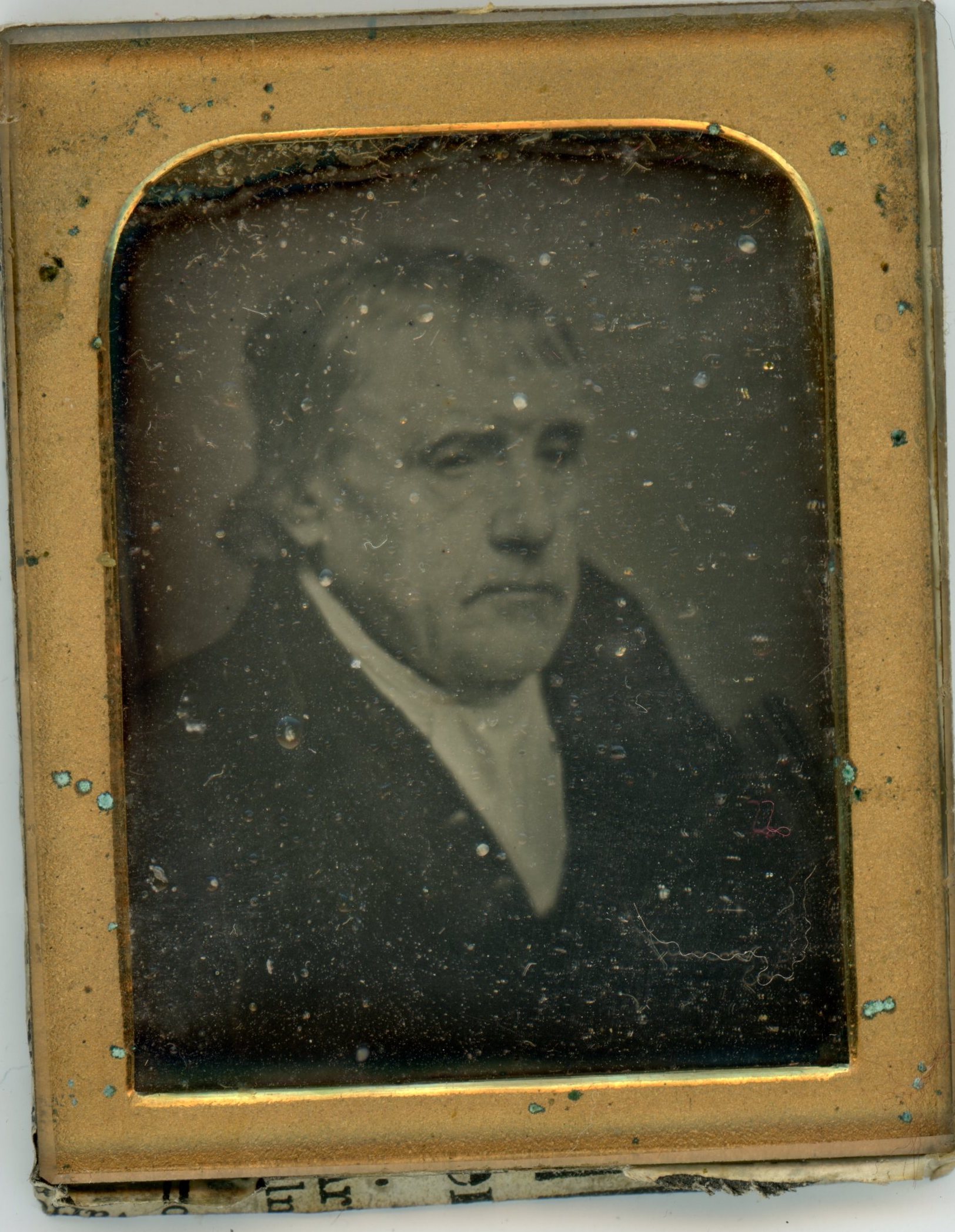

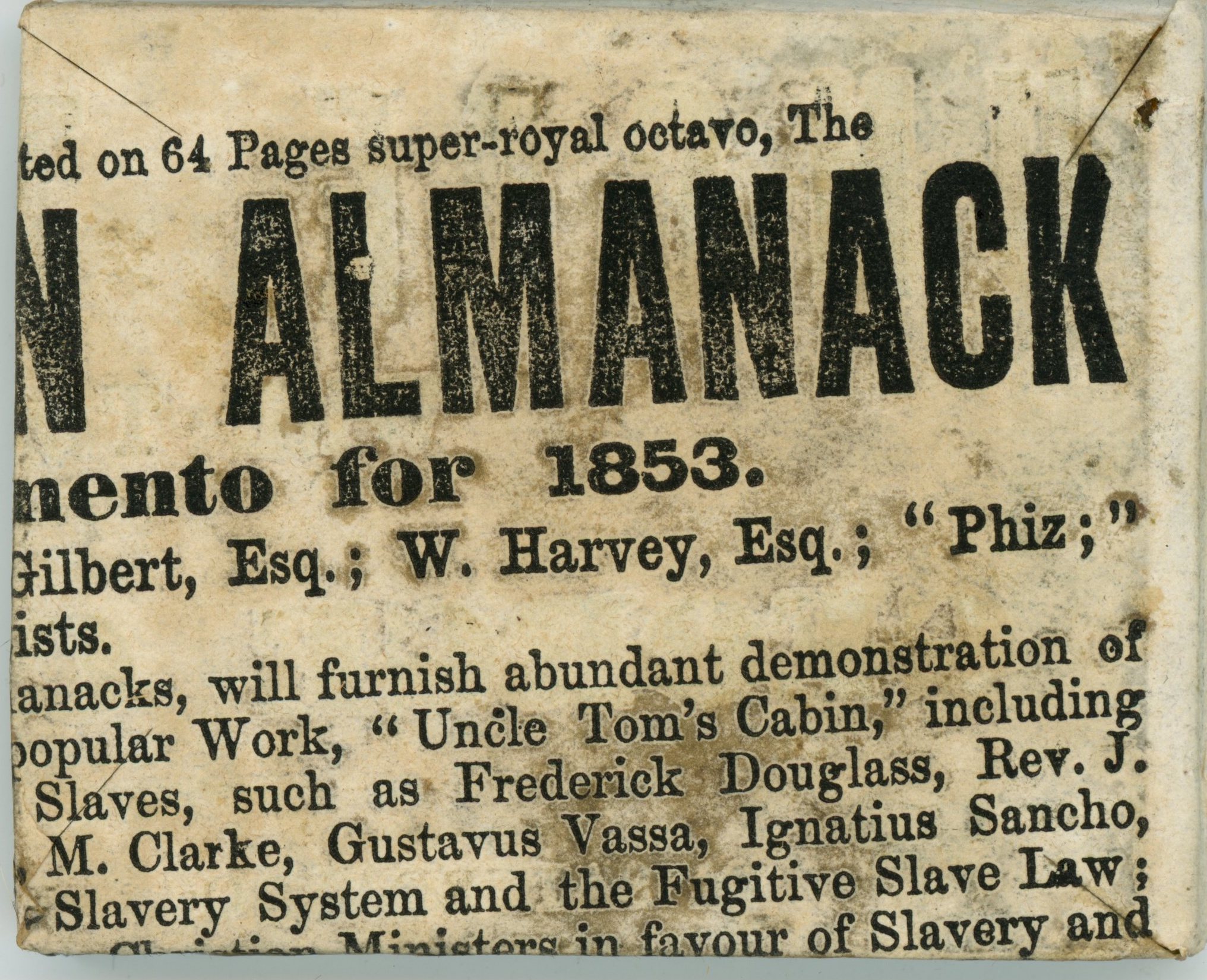

Steve Edwards, Field Note on a Discovery

Our second student voice is that of Julia Eberhardt, a student on the MA History of Art. Julia was telling me about being able to continue the research for her project on German art and men’s fashion in the eighteenth century when she went back to her hometown of Jena in Germany during the lockdown. I was green with envy, as many of you may be too, hearing about being able physically to access books and even archival material. But I thought that actually it was a hopeful story, and asked her to send me a few words about what it was like, using libraries post-lockdown. Over to Julia:

At the beginning of 2020 it was unthinkable how academically challenging this year would be for students and scholars all over the world. I had just started my MA History of Art in October 2019 and in the middle of my first Option Module, the situation in Europe grew more precarious by the day forcing us to have the last lectures of the term online. I was put on furlough by my employer at the beginning of April until further notice and decided to go back to my family in Germany for the time being. As for every fellow student I know, a phase of growing uncertainty began – how would we be able to ensure that our research would be sufficiently ensured and the quality of its outcome appropriate? How would we be able to access material, support and lectures throughout the remaining year?

As soon as I arrived in Germany it became clearer that the overall situation at the universities there was already considerably improved compared to the UK, due to the successfully established health and safety guidelines that the German government introduced at an early stage of the crisis. Libraries and other lecture rooms already started to open again at the end of May – a development, which gave me hope in the possibility of improvement of learning conditions in the UK. I was able to successfully continue my research at the University library in Jena, while staying in Germany until the beginning of July. The students there were encouraged to research the library catalogs thoroughly before visiting the facilities and indicate a range of books that they would like to consult or borrow, so the librarian could already prepare them prior to their visit. With allocated work places and the wearing of a mask while talking to staff members, the library users (including me) were able to continue their coursework and research successfully. I was also able to get into contact with professors of the University Jena and meet them in person, respecting the guidelines of social distancing. Also museum archives were open for research again as well as galleries and museum collections. Overall, as a researcher you were able to attend to business almost as usual, it was just necessary to plan and organise your work more upfront and become familiar with the odd sensation of wearing a face mask on a daily basis. Experiencing this, I am very optimistic that similar improvements in the UK will soon start to support our teaching and learning experiences and will hopefully allow for a fruitful and engaging autumn term at Birkbeck.

A p.s. from Leslie: The Birkbeck Library has announced that from this Monday 27 July it will be operating a Click and Collect service, allowing you to order and borrow actual books! They’ll also post books to those who can’t travel. Some details here, and more to come.

***

On that positive note, I end this post, and indeed my time as author/convenor/compiler of the Department of History of Art blog. My three-year term as Head of Department comes to an end on 31 July, at which point I pass the baton into Prof. Patrizia Di Bello’s extremely capable and creative hands, and head off into the sunny uplands of a year’s research leave. As mentioned in a previous post, this blog has become somewhat technologically creaky, so keep your eyes open for a new mode of communication from Patrizia.

Thanks for your attention, have a good summer, good luck with the coming term and year, and goodbye!

Leslie

. . Category: Uncategorized