In this guest blog Birkbeck research student Jemma Stewart discusses the language of flowers in Victorian literature and material culture. Jemma was a finalist for this year’s Anthony Davis Book Collecting Prize, organised by UCL Special Collections, and we are happy to be able to feature her collection and to have her share her thoughts with the readers of Bookish.

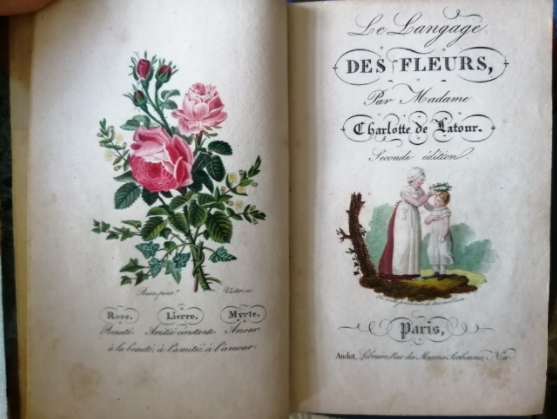

The language of flowers was a nineteenth-century cultural craze and popular fad allied to the gift book, or gift annual. An import from France, with romanticised Eastern origins and the notion of a codified set of meanings attributed to flowers, the books were translated, Anglicised and exploded in popularity in England and America. While floral symbolism, or floriography, did not originate in the nineteenth century, the formalised ‘lists’ perpetuated by the popular language of flowers anthologies ensured a continual dissemination and reimagination of this language of flora. My thesis considers floriography or floral symbolism in nineteenth-century Gothic fictions, so, I am primarily working with the night-side of nature. However, the material culture of the language of flowers anthologies provides an access point for my analysis as I seek to discover whether traditional floral meanings are subverted, adhered to or extended in Gothic texts.

Frequently derided as works of sentimental botany, accused of commodifying feeling and having little to do with the real lives of plants, the language of flowers books get a bad reputation in current times. However, as former Birkbeck scholar Nicola Bown notes, ‘sentimental art and literature invites us sympathetically to share the emotional world of those distant from us in time and circumstance […] to know more about what it means to be human ourselves’. The language of flowers books are evidence of one prolific way that the Victorians thought about human entanglements with nature. They are not completely devoid of botanical information in many cases, and, they gesture towards a female community of readership and inheritance rather than solely love intrigues or social climbing. There is plenty of potential for re-enchantment in revisiting this cultural craze.

Over the past year and a half, especially during the lockdowns, I became a low-level bibliophile and added to my collection of language of flower anthologies. When the Anthony Davis book collecting prize was advertised, this seemed like a great opportunity to share my admittedly hands-on mini reference library of sentimental flower books. Once the competition and its associated talks with UCL Rare Books Club had concluded, it was clear that I was a collector on two fronts — of the antique anthologies, but also of literary allusions. Does it mean anything when Lord Arthur Savile sends Sybil Merton a basket of narcissi and hands her a bunch of yellow roses (Oscar Wilde, Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime, 1887)? In The Lady of the Shroud (Bram Stoker, 1909) does Rupert’s commentary on the flowers worn by Teuta reveal a genuine awareness of floral symbolism:

“The veil was fastened with a bunch of tiny sprays of orange blossom mingled with cypress and laurel — a strange combination. Its sweet intoxicating odour floated up to my nostrils. It and the sentiment which its very presence evoked made me quiver.” (Bram Stoker, p. 188).

I would suggest that these floral inclusions hold significance and can prove a gateway to some rewarding analysis when looked at closely.

When assembling her study of the language of flowers in nineteenth-century culture, Beverly Seaton connected a perceived absence of the language of flowers in popular fiction to a lack of its real application in everyday lives (The Language of Flowers: A History, pp. 108–09). However, nineteenth-century cultural artifacts, including samplers, art, jewellery, music and valentines reveal a use of the language of flowers that extends beyond the gift books. The language of flowers books were often compiled in the format of poetry anthologies, and so the books and flower meanings themselves are framed around the literary iterations of flowers. Additionally, academics are continually uncovering floriography or explicit mention of the language of flowers in nineteenth-century realist fiction, particularly within the works of female authors who also composed stories in the Gothic mode. Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Rhoda Broughton, George Eliot, Charlotte Brontë, Letitia E. Landon, Elizabeth Gaskell, Edith Wharton, Louisa May Alcott, and Mary Wilkins Freeman all fall into this category.

It strikes me that there are three methods of working with floriography in fiction — searches within works for explicit mention of ‘the language of flowers’; decoding meaningful nosegays or bouquets exchanged between characters, and, interpreting the symbolic meaning of flowers as they bloom to become connected with character and plot. My collecting will continue as I progress through the PhD, gathering literary references and the language of flowers in material culture as I go.

With thanks to my supervisor, Dr Ana Parejo Vadillo, who introduced me to floriography and the language of flowers.

Many of the titles in Jemma’s collection can be viewed online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.