BIROn (Birkbeck Institutional Research Online) is Birkbeck’s open access repository. Its goal is to increase the visibility and reach of the College’s research by making it available across the web, in as close to its final form as possible.

But open access does not always mean accessible to all. According to gov.uk, “at least 1 in 5 people in the UK have a long term illness, impairment or disability. Many more have a temporary disability.”

This statistic indicates that ~20% of the potential audience for Birkbeck’s research may not be able to read it as easily as many of us take for granted. Open access and accessibility don’t always intersect.

The theme of this year’s Open Access Week, the week beginning 25 October, is: “It matters how we open knowledge”. This has never been truer than in the context of accessibility. If it’s significantly more difficult for some to read open access research than others, can it really be called open?

In September 2020, Birkbeck and our partners at CoSector (who host and manage the repository) collaborated on an accessibility statement for BIROn. The statement outlines the progress made to ensure BIROn now meets many of the requirements of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1), an internationally recognised set of recommendations for improving web accessibility.

However, there is still work to do.

The EPrints software we use for BIROn is a “core” build from CoSector which is then adapted for different institutions depending on their needs. It is this core build (not the modified version specific to Birkbeck) which was tested using the WAVE accessibility tool. Planned upgrades to the core build aim to address the areas where the site is still unable to meet requirements. You can see what needs work in the roadmap.

The second element

Although the BIROn web site is now much closer to offering an optimised experience for users with accessibility needs, the full-text files it hosts are a more complex matter.

BIROn was established in 2007, and contains some materials which are even older, including PDFs which do not meet accessibility and archiving standards. Files originate from a huge variety of sources and come in many formats; they may contain abbreviations, formulae, tables, and images which screen readers and other assistive technologies struggle to interpret. Bringing every file up to standard will be a massive, resource-intensive task.

What are others doing?

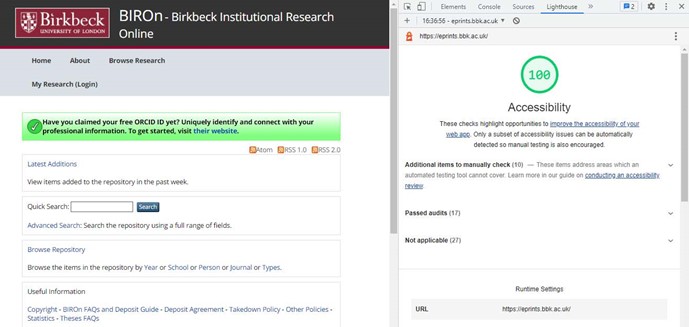

The repository team at the University of Kent have blogged about their experiences with checking accessibility on their repository, KAR. The blogs include helpful insights into tools such as Lighthouse (which is built into Chrome). When we ran a check on BIROn’s accessibility in Lighthouse, it scored 100% for both desktop and mobile iterations (see figure below).

As Kent’s blog outlines, this was just the beginning of the process. The KAR repository contains almost three times the number of records in BIROn, so the challenges for full-text file accessibility are even more acute.

The Kent team therefore created a button for users to request an accessible version of a repository file. Depending on the document, this might mean significant work is required, with a thesis taking up to three weeks and requiring the input and expertise of the original author. However, some files can be converted in less than ten minutes. The KAR team also discovered that the vast majority of the initial requests for accessible versions were because the requester was unclear about what was being offered; ultimately, just two of the first 64 requests needed to be actioned.

You can read about the challenges the KAR team faced on these insightful blogs. Here at Birkbeck, we are also beginning to face up to these challenges, mindful of our legal duty to anticipate the changes that need to be made and not just react to them.

Padlock image by Kerstin Riemer from Pixabay