Lotte Eisner: Writer, Archivist, Curator : an interview with Julia Eisner by Fernando Chaves Espinach

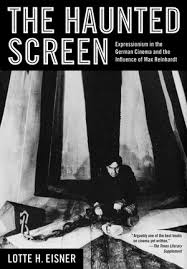

That Lotte Eisner (1896-1983) has a place in film history is no surprise, but over the years it has become increasingly difficult to define exactly that what might mean. Mostly remembered as a mentor and champion of the New German Cinema, and known to film scholars for her influential study of German cinema of the 1920s, The Haunted Screen (1952/1969) and further books on F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang, the longtime archivist of the Cinémathèque française lived through the rise and fall of her nation’s cinema, the most traumatic war of the century, her exile in Paris, the burgeoning cinephile culture of the 50s and the mad, wild innovations of the 60s. But what was her role in shaping this story?

That Lotte Eisner (1896-1983) has a place in film history is no surprise, but over the years it has become increasingly difficult to define exactly that what might mean. Mostly remembered as a mentor and champion of the New German Cinema, and known to film scholars for her influential study of German cinema of the 1920s, The Haunted Screen (1952/1969) and further books on F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang, the longtime archivist of the Cinémathèque française lived through the rise and fall of her nation’s cinema, the most traumatic war of the century, her exile in Paris, the burgeoning cinephile culture of the 50s and the mad, wild innovations of the 60s. But what was her role in shaping this story?

Lotte Eisner: Writer, Archivist, Curator was a symposium held on October 26 and 27 at Birkbeck, University of London, and King’s College, supported by the Birkbeck Institute for the Moving Image, the Goethe-Institut London, DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service), King’s College London, and the German Screen Studies Network.

The encounter included a screening of Sohrab Shahid Saless’ The Long Vacation of Lotte H. Eisner/ Die langen Ferien der Lotte H. Eisner (1979), one of F.W. Murnau’s City Girl (1930), trailer and presentations from Naomi DeCelles (UC Santa Barbara), who looked at Eisner’s writings on arts and film from the 20’s and 30’s; Professor Michael Wedel (Cinepoetics Berlin/Film University Potsdam), who analysed Murnau’s Faust and Sunrise from Eisner and Eric Rohmer’s perspectives; Professor Janet Bergstrom (UCLA), who detailed the evolution of Eisner’s writings on Murnau; and Julia Eisner (King’s College London), who is doing her PhD research on the life and work of her great aunt. Eisner shared her thoughts with me after the symposium.

Fernando Chaves Espinach (FCE) : What drove you to dive into Lotte Eisner’s life? In which ways did you feel our perception of her work was incomplete?

Julia Eisner (JE): Lotte Eisner was my great aunt and when I was growing up, I knew her both as a member of my family and as an important figure in the history of film. Our family were all very proud of her as author of The Haunted Screen and, although we knew she also worked at the Cinémathèque française, I think it’s fair to say that we were not clear as to what she did there.

However over decades, although still revered and referenced, Lotte Eisner’s reputation and, in particular her career, seemed to me to have become confused and somewhat overlooked. A rather superficial but nevertheless representative example of this was her previous Wikipedia page (which I have since rewritten) stated that Lotte Eisner was a poet amongst other things. Equally I found that an online search brought up many references to Lotte, but always as defined by other people, such as Werner Herzog, Henri Langlois or Fritz Lang. It was very difficult to find any material that engaged with her and her work, other than a straightforward biography, very often wrong, that did not immediately refer to her in relation to someone else, or to an institution. That was my motivation to investigate further and begin my PhD project in 2016.

However over decades, although still revered and referenced, Lotte Eisner’s reputation and, in particular her career, seemed to me to have become confused and somewhat overlooked. A rather superficial but nevertheless representative example of this was her previous Wikipedia page (which I have since rewritten) stated that Lotte Eisner was a poet amongst other things. Equally I found that an online search brought up many references to Lotte, but always as defined by other people, such as Werner Herzog, Henri Langlois or Fritz Lang. It was very difficult to find any material that engaged with her and her work, other than a straightforward biography, very often wrong, that did not immediately refer to her in relation to someone else, or to an institution. That was my motivation to investigate further and begin my PhD project in 2016.

FCE: How can we account for the lack of information regarding the extent and variety of her work?

JE: I haven’t got a definitive answer to this question, but I speculate that her status as an educated, intellectual, career-driven, unmarried woman who began her working life in 1924 did not fit into a socially acceptable gender role. But there were other reasons, I suspect. She was working with a man, Henri Langlois, who was larger than life, charismatic and who presented himself as the public face of the Cinémathèque.

Equally as I have discovered, within the film world, she was a polymath, able to work in different fields – journalism, film and theatre criticism, author of 3 books, lecturer, film jurist, film history researcher, archivist and exhibition curator (to name but a few).

So, unlike Iris Barry for example who was both married and essentially focussed on one job as curator of the Film Library at MoMA, Lotte Eisner was hard to pin down and understand. In fact her working methods and attitude towards work are, I believe, quite contemporary and can be compared to the way in which (particularly in the arts) boundaries between disciplines are now blurred and knowledge is applied broadly. Lotte Eisner, with her PhD in art history and archaeology applied her knowledge, education and cultured background to film in all its manifestations – as a critic, a journalist, an author and as an archivist and curator.

But to try and answer your question I suppose I would say that gender played a large part in the way in which, as a working woman, she is now mis-remembered and that to an extent she was overshadowed by Langlois, but I also think that being a refugee and living in exile also played its part. She had lived through some very difficult times, her mother was killed by the Nazis and her family dispersed, so her dedication to, and her love of her work at, the Cinémathèque after the war became far more important and in a way overwhelmed any other impetus to have either a private life or to shift away from the status quo at the Cinémathèque.

But to try and answer your question I suppose I would say that gender played a large part in the way in which, as a working woman, she is now mis-remembered and that to an extent she was overshadowed by Langlois, but I also think that being a refugee and living in exile also played its part. She had lived through some very difficult times, her mother was killed by the Nazis and her family dispersed, so her dedication to, and her love of her work at, the Cinémathèque after the war became far more important and in a way overwhelmed any other impetus to have either a private life or to shift away from the status quo at the Cinémathèque.

FCE: In some ways, as you mentioned in the symposium, Eisner was in many ways ‘a node for reconstituting a broken community,’ that of German exiles after WWII. How can her letters shed light on this process? What do her collecting practices tell us about the cultural memory of German film artists?

JE: Lotte Eisner was naturally an extremely personable and likeable character and she was a prolific writer and letter writer. Unfortunately, her letters at the Cinémathèque have not been collected so thousands of them are spread across their archive. I also have several hundred in her private archive. Examining her letters has illuminated her work (and confirmed her delightful personality), but also has given me a useful snapshot of activity at the Cinémathèque during its heyday in the first two decades after the Second World War.

By 1945 on her return to work, she knew that all efforts had to be made to track down the filmmakers, cinematographers, designers and the materials of their work, from the so-called ‘Golden’ age of German silent cinema – the first two decades of the twentieth century. Lotte Eisner either knew many of these people from pre-war Berlin or knew of them so relying on her own knowledge and using the Cinémathèque’s growing collection of German silent film she wrote to as many as she could find.

Like her, many were living in exile or were displaced in some way, and in many cases assumed they had been forgotten; but what sets her drive to connect and contact these people apart was the emphasis she put on finding the art and set designers of these films. Many of the letters from set designers to Eisner iterate this point, stating that their work was about to be burnt or that it had just been dumped somewhere. Eisner then travelled to Germany twice during the 50s to borrow or purchase items for the Cinémathèque.

Like her, many were living in exile or were displaced in some way, and in many cases assumed they had been forgotten; but what sets her drive to connect and contact these people apart was the emphasis she put on finding the art and set designers of these films. Many of the letters from set designers to Eisner iterate this point, stating that their work was about to be burnt or that it had just been dumped somewhere. Eisner then travelled to Germany twice during the 50s to borrow or purchase items for the Cinémathèque.

So in collecting the art work, set designs, maquettes and films of German silent cinema, she also built up or rebuilt connections between and among the dispersed and broken international film community. This also turned the Cinémathèque, and Eisner in particular, into a kind of hub of knowledge and information helping people to reconnect.

FCE: From your point of view, what picture of Lotte Eisner emerged through the symposium?

JE: It’s difficult for me to answer that question in a simple way. I was incredibly impressed by the amount I learned from Naomi DeCelles about Lotte Eisner’s journalism at the Film Kurier in Berlin from 1927-1933, which reinforced my understanding of her range of ability to write about more or less anything.

But equally the other two presentations engaged with, and underlined the importance of, her work on F.W.Murnau, which has so far gone somewhat unrecognised. She believed Murnau was the greatest German film director and wrote the first biography. I hope a broader, more comprehensive understanding of Lotte Eisner and her work came out of the event.

FCE : Is there any plan for further academic encounters or publications related to the symposium?

JE: I hope so…