Going Beyond the Beach: Programming a Caribbean Film Festival in Miami

Jonathan Ali is currently studying for an MA Film Programming and Curating.

At the start of this year, my decade-long association with the Trinidad and Tobago Film Festival—a Caribbean-themed film festival in my native country—came to an end. Over the ten years spent with that festival I had built up quite a store of knowledge about, not to say enthusiasm for, Caribbean cinema. It was thus a great pleasure several few months later to be invited to programme—along with two other programmers—another festival focused on Caribbean content, this time in the city of Miami: the inaugural Third Horizon Caribbean Film Festival.

Miami is home to a significant Caribbean diaspora community, which has largely been under-served when it comes to seeing cinematic content from the region. Third Horizon therefore gave us the opportunity to programme for this audience—as well as Miami cinephiles in general—not only the latest films by Caribbean filmmakers, from the Caribbean diaspora and non-Caribbeans at work in the region, but also older, even classic films that had never been screened in Miami.

Unlike my previous festival, which was a fairly large, multi-venue event taking place over two weeks, Third Horizon ran for just three days and one night (September 29 to October 2) at one location, the O Cinema, a one-screen, 120-seat independent picture house in Miami’s arts-centric Wynwood district. There were nine programming slots in all, which led us to decide upon a lineup of eight features plus a package of shorts.

Given the large pool of films from which to choose and the relatively small number of programming slots, curating the festival’s lineup was a challenging task. We set ourselves certain criteria. One criterion was that all of the region’s major groupings in terms of colonial heritage—English, Spanish, French and Dutch—had to be represented. We also determined to have, as much as possible, equality when it came to the genders of the directors of the films selected (we didn’t achieve parity here, unfortunately, with three female directors and five male directors when it came to the feature films). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we had a political aim: we wanted the films we programmed, even if they were genre films, to have a certain ethical integrity about them, and to go beyond clichés of the Caribbean as an exotic, sun-drenched tourists’ paradise, a place made up largely of bikinis and beaches.

Being quite familiar with the feature-film work made by filmmakers in the Caribbean and the diaspora we decided not to have a call for entries for features, and put one out only for short films. (Disappointingly, nothing we saw in that call made the grade, and so every film we ended up programming was a film previously known to one, two or all three programmers.)

After several months of pre-screening, deliberation and negotiation with filmmakers, we settled on our programme. In addition to the film lineup we curated an exhibition by a Caribbean contemporary artist working in multiple media. On the lighter side of things, for every night of the festival, we also “curated” a party featuring Caribbean music for festival guests and audience members. Also on the lighter side, we managed to secure the sponsorship of a Jamaican beer company that generously offered free product to all audience members at every screening. Well, anything to get bums on seats!

Film festival opening nights are usually a place for unchallenging, crowd-pleasing fare. Bravely bucking this trend, we programmed as our opening selection a slow-paced Haitian fable with a fractured narrative, Ayiti Mon Amour (Guetty Felin, 2016). Set in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake that ravaged Haiti and partly inspired by Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959), Ayiti Mon Amour as our opening film would, we felt, signal the seriousness of our enterprise. We also expected Miami’s sizeable Haitian community to come out for the film, which they did.

Film festival opening nights are usually a place for unchallenging, crowd-pleasing fare. Bravely bucking this trend, we programmed as our opening selection a slow-paced Haitian fable with a fractured narrative, Ayiti Mon Amour (Guetty Felin, 2016). Set in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake that ravaged Haiti and partly inspired by Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959), Ayiti Mon Amour as our opening film would, we felt, signal the seriousness of our enterprise. We also expected Miami’s sizeable Haitian community to come out for the film, which they did.

The next day there were two screenings. The first was of a work in progress, screened for an invited audience, of a Trinidad-set neo-gothic drama, Moko Jumbie, a first feature directed by a Trinidadian-American filmmaker, Vashti Anderson. The director benefitted from constructive feedback from the audience of mostly film industry professionals, and is now finishing her film with hopes of a festival premiere in early 2017.

The second screening was of a documentary, The House on Coco Road (Damani Baker, 2016). The film focused on the filmmaker’s mother, formerly an assistant to the famed social activist, Angela Davis, who in the early 1980s moved her family from the United States to the island of Grenada to take part in the socialist revolution there, only to flee after the prime minister and several members of his cabinet were killed by the military and US president Ronald Regan sent American troops to intervene. Here again was a film with a serious, overtly political subject, and again we were gratified that a large, enthusiastic audience turned out for the screening and question-and-answer session.

The following day began with the package of shorts, five in all, from different countries and varying widely in content and tone. Next up was a British film, Generation Revolution (Cassie Quarless and Usayd Younis, 2016), a documentary about black and brown social activists—many of them of Caribbean descent—fighting for justice on the London streets. The subjects in the film had been inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States and the filmmakers, who attended the festival, took the opportunity provided by the question-and-answer session after their screening to invite activists from Miami’s Black Lives Matter chapter to take part in the discussion.

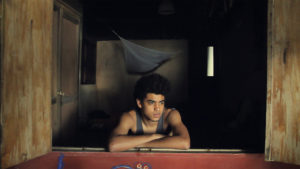

The day was rounded out by the screening of God Loves the Fighter (Damian Marcano, 2013), a neo-realist crime drama set on the streets of Trinidad and Tobago’s capital, Port-of-Spain, and which previously had been a selection of the International Film Festival Rotterdam and London’s East End Film Festival, among others. Yet again, here was a film tackling a serious subject, but doing so through the familiar, engaging tropes of the genre film.

Our repertory selection, the British film, Pressure (Horace Ové, 1976), opened the festival’s final day (sadly, as the O Cinema is a digital-only venue, there was no question of screening a 35mm print). The story of a young Afro-Caribbean man living in London and trying to negotiate between various identities, the film paired nicely with the one that followed it, the documentary The Stuart Hall Project (John Akomfrah, 2013), a portrait of the Jamaica-born, British intellectual of the left and pioneer of modern multiculturalist thought.

Our repertory selection, the British film, Pressure (Horace Ové, 1976), opened the festival’s final day (sadly, as the O Cinema is a digital-only venue, there was no question of screening a 35mm print). The story of a young Afro-Caribbean man living in London and trying to negotiate between various identities, the film paired nicely with the one that followed it, the documentary The Stuart Hall Project (John Akomfrah, 2013), a portrait of the Jamaica-born, British intellectual of the left and pioneer of modern multiculturalist thought.

Memories of a Penitent Heart (Cecilia Aldarondo, 2016) ended the festival on a poignant note. A personal documentary, the film bears witness to the filmmaker’s attempts to excavate the previously hidden narrative of her deceased uncle from Puerto Rico, a gay man who died of AIDS in New York in the 1980s and came from a deeply conservative Roman Catholic family. Not only was the documentary an exemplary piece of filmmaking embraced by the audience, it also fulfilled another wish of ours, which was to include at least one LGBT-themed film in the lineup.

Having successfully navigated the first edition of the festival, the Third Horizon team is looking forward to next year’s event, and in identifying aspects of our programming that—given our parameters—could be done differently. More overtly crowd-pleasing fare, for example, might be in order. Whatever we decide, however, we are committed to our mission of subverting stereotypes, and to presenting the Caribbean region as so much more than just sun, sea and sand.