Peter Fifield on Oxford, by Martin Parr

Peter Fifield on Oxford, by Martin Parr

This exhibition occupies Blackwell Hall, the large foyer of the Bodleian’s Weston Library, which reopened in 2015 after a long and expensive refurbishment. I went here in a lunch break from my research in one of the other, older parts of the Bodleian, where I spend much of my time. It is a beautiful open space that channels the desire of the university to be a public institution. It resembles the foyer of the British Library in having an open plan café, a gift shop, space for various displays, and an extensive plate glass mezzanine allowing one to see some of the books stored there. This is, then, the public aspect of the university, which the tourists more often glimpse only through a small college door.

The decision by the Bodleian and the University Press to invite Martin Parr to continue his study of the British establishment is suggestive. His style is highly colourful, brightly-exposed documentary photography, offering new and sometimes harsh perspectives on familiar themes. He is most well-known for his photographs of the working classes on holiday in New Brighton, recorded in The Last Resort (1986). The photographs are sufficiently stark that they call to mind the amateur’s own holiday snapshots, which show things slightly rougher than memory may suggest. Sometimes the photographs seem mocking, sometimes fond. Parr’s style was once considered outrageous, but has since been absorbed into the canons of good taste, the qualities of his images now widely recognised. It is not too mean to suggest that he was the next big thing a few things ago. His suitability to photograph the ‘establishment’ is not the fruit of a change in style, rather his consistency is itself now a safe bet for the commissioner to appear mildly adventurous but not iconoclastic.

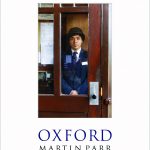

The Press has produced a large hardback book of the Oxford photographs, which could serve equally as a souvenir or an art book. On its cover is one of the Christ Church porters—a security guard of sorts—employed to look over those entering and leaving the college to check for interlopers. They are themselves a favourite tourist spectacle; wearing bowler hats and dressed smartly they will appear in many of the private photographs taken by the city’s tourists. But they have also become notorious for their dubious judgement, turning away black students assuming that they were contractors engaged on building work. The porter shown is himself non-white, in line with much of the university’s own press material but not the ethnic profile of the institution. He looks directly at the camera through the glass of his lodge box, by which he is framed. The glass of the box reflects the photographer’s own image and, to press the point home further still, the image is set within the large white margin of the book’s glossy dust-jacket, in which one can see one’s own face.

It is difficult to read clearly the sense of this dizzying self-consciousness. The university has described the exhibition as offering a behind-the-scenes look at the institution, and we see private feasts, student clubs, laboratory researchers, and quirky traditions that are otherwise invisible. They are, consistently with Parr’s style, more real and less glamorous than anything seen in Porterhouse Blue, Decline and Fall, or Brideshead Revisited. Gowns slip awkwardly off shoulders, conversation between dons is frozen into an awkward and mute tableau in which everyone looks less than pre-eminently intelligent. Photographs of student nights out are as unflattering as any image hastily caught on a phone: pushing towards a pizza stand at a ball, sitting about in a sparsely-populated marquee. Other images are more conventionally formal: the university’s bedels stood in formation with their ceremonial maces and gowns, in front of the golden stone of the Sheldonian Theatre. It would sell well on a postcard.

A number of the photographs capture the ritual of ‘trashing’, when students finishing their exams in white tie and gown are ambushed by their friends, sprayed with shaving foam, flour, confetti, glitter, champagne and worse, before they rinse off by jumping into the river Cherwell. This practice is forbidden by the university, aware that the spectacle of waste is morally problematic. This is the popular version of the Bullingdon Club’s excesses, with its history of destroying restaurants and burning cash in front of the homeless. However, the ban is not enforced but sidestepped: the students are guided out of the back entrance of the examination school where an area is carefully cordoned off for their wild celebrations. Similarly, the photographs of Summer Eights, the high point of the college boat clubs’ year, show barbecues, drinking societies and high jinks in blazers, all contained in the effective quarantine zone of boat house island. A caption notes that the winners will burn a boat after a celebratory dinner, another version of the trashing dilemma.

All of this suggests that in seeing behind the scenes we are still looking at a carefully prepared image. The double framing of the book’s cover reminds us that even a fresh look is one that is self-aware, that has looked itself up and down first. To put it kindly, no naïve or fresh view of the university is possible. To be more suspicious, the university exploits its ambiguous status. Either way, it strikes me that trashing and boat-burning represent an important subject for a documentary photographer. The university disapproves in that it doesn’t wish to show itself insensitive to issues of poverty, nor exclusive to students only from wealthy backgrounds. But these ceremonial acts of destruction are, I suggest, closely connected to the ceremonial maces, gold-trimmed gowns and matriculation ceremonies. The wealth of the place, its grandeur, and the sheer wastefulness that accompanies such abundance—too much history, money, land, and too much intelligence—is bound up with its beauty, its traditions, and its functions within the country. These include both a whipping boy for moral and political outrage, and an embodiment of cultural continuity and scholarly rigour. This made me think of the French theorist Georges Bataille’s idea of a general economy, which has the spectacular destruction of excess—the ‘accursed share’—rather than growth and productive labour at its centre. In Parr’s exhibition as in the university it depicts, such plenitude is both a compelling and an unsettling sight. I didn’t entirely like it, and I went back the next day to see it again.

by Peter Fifield, October 2017