Joseph Brooker on The Tempest at the Barbican

Joseph Brooker on The Tempest at the Barbican

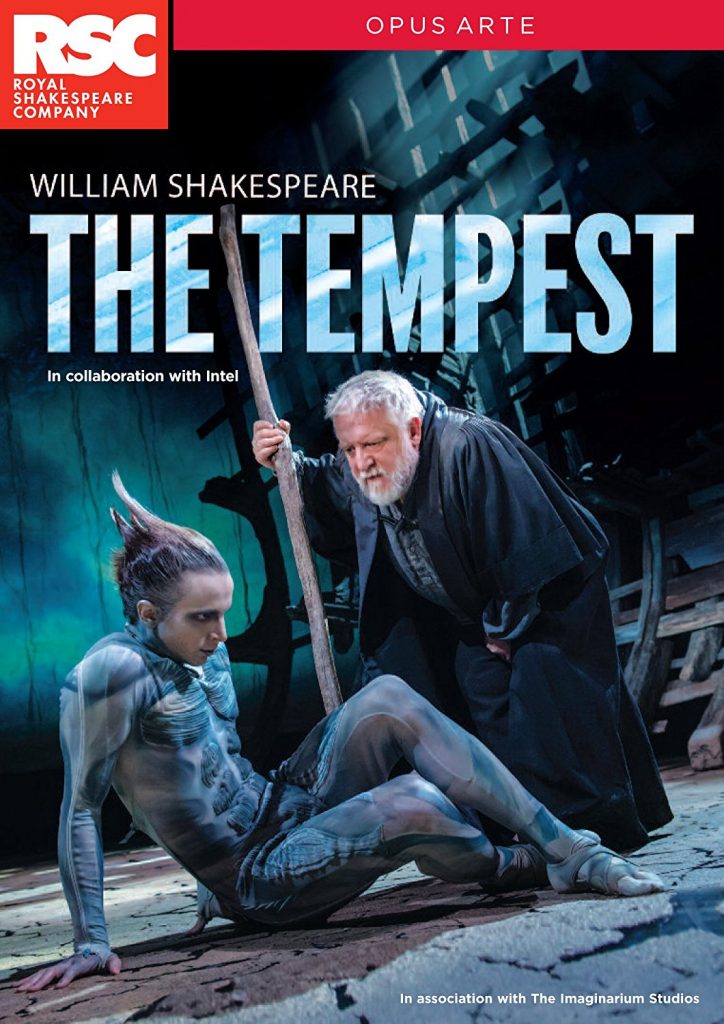

Like many people I think of myself as revering William Shakespeare, and also imagine that I know the outline of his late play The Tempest (c.1611). But a few minutes into the current RSC production at the Barbican, directed by Gregory Doran with Simon Russell Beale as the wizard Prospero, I started to realise that I hadn’t seen Shakespeare on stage for some time, and haven’t looked closely at the text of The Tempest for still longer. Watching Prospero provide lengthy back-story to his daughter Miranda, I had no doubt that Shakespeare’s magniloquence was reliably in place in every line on the page, but was less sure that rattling through it in a lengthy monologue, voice straining on a bare cavernous stage, was a good mode of narrative exposition. Maybe, I thought, I’d watched more superhero movies than was good for my ability to concentrate on this stuff. For that matter, before the play I’d spent four hours with Martin Keown and Kevin Kilbane on Radio 5live: perhaps this hadn’t left my English at Shakespearean levels.

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

A gain from my long separation from The Tempest, though, was frequent surprise at what actually happened. When Prospero’s slave Caliban lay under a sheet and was discovered by a clown with painted face and horn, I felt bewilderment and intrigue: was this clown indeed, as Caliban himself says, a spirit of Prospero’s island? Only gradually did I realize that the clown was Trinculo, yet another of the dispersed survivors from the opening shipwreck (and actually named as a Jester in the dramatis personae). Did you remember that Ferdinand and Miranda have a wedding ceremony blessed by a set of goddesses who appear out of nowhere and sing opera? (In the text a stage direction stipulates: Juno’s car appears in the sky, which seems at least as ambitious as Exit pursued by a bear.) Or that Caliban, Trinculo and their fellow chancer Stephano are deterred from an attack on Prospero by the spirit Ariel conjuring a blitz of raucous barking dogs? (Enter divers spirits, in shape of dogs and hounds, hunting them about.) Quite possibly, but you still might never have seen these moments realized in such spectacular form as in Doran’s production. Screens, projections, graphics, lights: Ariel’s magnified image floating in a great cylinder, looking like the Silver Surfer and giving me hope that this play wasn’t so incompatible with superhero movies after all. The plainness of Prospero’s first scene was transcended by all these, but also, for me, by the simple interest of character and action. How would Caliban’s motives emerge? What would transpire amid the party of royal shipwreck survivors? Would Miranda’s high opinion of Ferdinand dip if she ever saw another man? By the late scene when Prospero abjured his magic and broke his staff, the dynamics of character and emotion had become compelling, and I had even caught up with the language, ascending from Keown to appreciate the tremendous chunky vividness of this:

I have bedimmed

The noontide sun, called forth the mutinous winds,

And ‘twixt the green sea and the azured vault

Set roaring war: to the dread rattling thunder

Have I given fire, and rifted Jove’s stout oak

With his own bolt: the strong-based promontory

Have I made shake, and by the spurs plucked up

The pine and cedar.

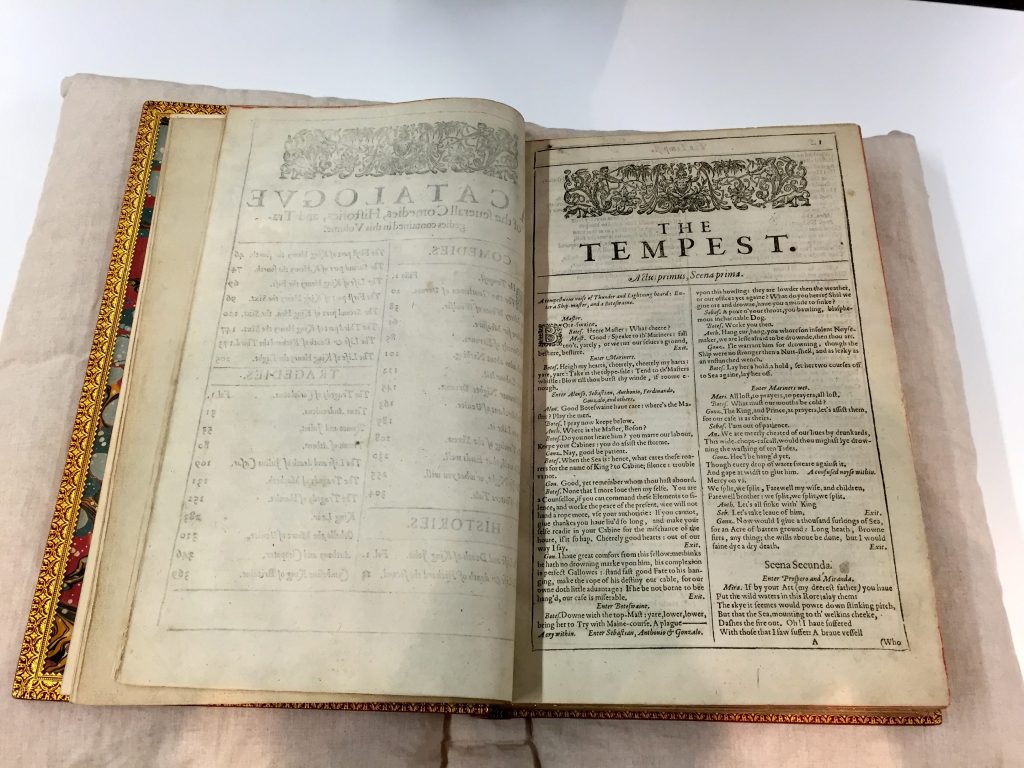

From Shakespeare’s First Folio. [Image by ptwo under a CC BY-NC license]

From Shakespeare’s First Folio. [Image by ptwo under a CC BY-NC license]

A standard Michael Billington review of a play like this will say something like: ‘Watching Gregory Doran’s production, I came to realize how much Shakespeare’s play is about the power of art’. Sure. But my reaction was more literal. Watching this production, I came to realize how much the play is about magic. Dancing spirits of wood and water taking over the action from human beings; spells cast to put people to sleep or paralyse them. This was striking, because I don’t especially associate Shakespeare with the supernatural but with secular reality: merchants, rogues, deals, motives high and low, realpolitik, negotiation, battles, beer – the kind of thing that fills Henry IV. To see a Shakespeare play so magical is to realize how un-magical most of Shakespeare is, with a few important exceptions, even though it derives from a world where more people believed in both angels and alchemy than they do now. I also started to reflect that The Tempest belongs to the literary history of fantasy. Put simply, when Prospero’s dull cloak had stopped reminding me of Ben Kenobi, his staff and books (unseen here, apparently stored on high) reminded me of Gandalf. Not that The Tempest can be a key progenitor of this mode, a role more solidly occupied by Old Norse sagas and Arthurian romance, but perhaps it shares in the same tradition. This in turn made me wonder if Shakespeare could be related to the other major modern genres. Henry V and Anthony Cleopatra are evidently historical fiction, Much Ado About Nothing romantic comedy, Macbeth Gothic or Horror; how about Measure for Measure as crime, The Merchant of Venice partaking of courtroom drama and Othello as erotic thriller? Science fiction is another matter, relying on a post-Shakespearean level of technological development, but there remains an imaginative dialogue between them – most evidently in Forbidden Planet’s remake of The Tempest itself.

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

The one thing I had remembered about The Tempest all these years was less magical and more ‘materialist’: the idea that it dramatizes a colonial situation, exemplified by Caliban’s resentful insistence that he has learned his masters’ language in order to curse in it. Doran’s production seems to take this head on, with a black actor (Joe Dixon) as Caliban – albeit clad in a tight beige suit with swollen belly. It seems a standard view that the play was inspired by attempts to colonize the Americas, yet this is not explicit in the script, whose reference points are from Milan and Naples to Tunisia: the sea in question is apparently the Mediterranean, not Caribbean. I was reminded of how awkwardly Shakespeare’s narrative fits with any well-meaning postcolonial analysis, but that the awkwardness can be part of the point. Thus Caliban’s faith in the drunken sailor Stephano as a new master sees him cry ‘Freedom!’ with a doomed poignancy I can still feel, remembering the scene days later. Shakespeare seems to be playing on a standard carnivalesque trope of inversion, with the clowns deluded that they can get the upper hand. Viewed politically, Caliban’s new subservience to Stephano (peculiarly reminiscent of, and perhaps a direct influence on, Gollum’s to Frodo as they cross the Dead Marshes in The Two Towers) is painfully humiliating. Yet I wonder if it encodes a reality of master-slave relations, in which the oppressed is all too ready to follow a new master as the price of escape from the old. The would-be comic structure might get at something troubling but insistent about colonial psychology.

Gollum, Frodo and Sam cross the Dead Marshes. [Image used under fair dealings provisions]

Gollum, Frodo and Sam cross the Dead Marshes. [Image used under fair dealings provisions]

Caliban’s very last appearance marks a change. Chastised by Prospero to return to his cell, he suddenly rises to full height, looking taller than everyone else on stage. Prospero and the rest step back in trepidation. It is as though, from all the grovelling enslavement, Caliban has become Shelley’s lion after slumber, realizing his potential power over the oppressors – though in this case they are many and the oppressed few. Towering over Prospero, Caliban speaks his lines of deference – ‘I’ll be wise hereafter, / And seek for grace’ – with a new self-belief and scorn, disdainfully snapping logs of wood as he stalks off stage. If anything, the implication is that to be ‘wise’ is to gain a better consciousness of his oppressed condition, and the ‘grace’ he seeks would be authentic liberation. Perhaps the recent adventure with a failed rebellion has transformed his understanding. None of this is specified in the script, but the reinterpretation of the scene echoes the notorious difficulty at the end of The Taming of the Shrew, where Kate’s declaration of subservience to her husband is nowadays often played for irony. At this historical moment, in both cases, it seems necessary to find something in the script to redeem it. The effect of Caliban’s transformation, though abrupt, is powerful.

Yet still more than Caliban, Ariel is the production’s wandering star. His presence is assisted by special effects, but the actor Mark Quartley himself is at the heart of it: constantly on tiptoe, always poised to fly from one location to the next, a creature made of potential movement. I know that all the actors on stage will have learned to adapt their bodies to move in different ways – not least Dixon’s hunchbacked and loping Caliban – but Quartley takes this to another level. He’s like a ballerino, seamlessly conveying a sense of living on another plane from the human beings he floats among. It’s curious that the magic is supposed to be Prospero’s, but so much of it seems reliant on the agency of this dazzling figure: almost as though, like Caliban, he has never realized the true extent of his own powers.