Joanne Winning at the Harry Ransom Center, Texas

Joanne Winning at the Harry Ransom Center, Texas

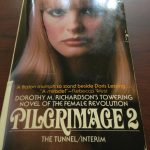

Popular Library 1976 edition of Pilgrimage

This summer I have been on a Research Fellowship at the Harry Ransom Center, at the University of Texas in Austin. The Ransom Center has one of the most extensive collections of modernist papers, manuscripts and artefacts in the world. It is a place where the materiality, and indeed the fragility (more of that in a moment…) of art, literature and photography becomes overwhelmingly obvious.

I have working on the papers belonging to the historically-overlooked female modernist author Dorothy Richardson, contemporary of Virginia Woolf but a minimally-discussed peer by comparison. Together with colleagues from the Universities of Birmingham, Keele and Oxford, I am undertaking to produce a new critical edition of the 13-novel series Pilgrimage (which will be published in 6 volumes by Oxford University Press) and, for the first time, a 3-volume annotated edition of all of Richardson’s correspondence, letters which begin in 1900 and take her through to her last shaky missives in 1952 (if you are interested, our Project website is at http://www.keele.ac.uk/drsep/). It is a huge undertaking but the grain and texture of it will add to our understanding of the cultural contexts of modernism in the first decades of the twentieth century, and of the warp and weft of the networks of cultural production through which modernism comes to be, will be invaluable.

Richardson wrote a great deal: the vast fictional structure of Pilgrimage, its 13 novels fictionalising her own journey from youth to middle-age and the act of writing; short stories, articles and reviews; and letters, by the dozen, to a wide range of correspondents. The letters tug the researcher who must date and annotate them (which is to say, in this instance, me) across a sweeping landscape of experience and cultural references, from high-end French perfume, to art cinema in the 1920s, to the first English translations of Proust, to the name of horses running at Newmarket as racing tips. Interpretative and ethical questions start to spill and multiply as I begin the process of editing. What is the benefit of tracing the detail of a life, and the other lives to which it connects intimately and intellectually, now gone? What do I hope to contribute to our present in reconstructing the lives of writers and artists and the complex relation of their lived experience to their aesthetic objects? What is my ethical relation to the secrets and repudiations embedded in the lives and texts I am researching? Above all else, the archival research I am doing has made me think about fragility. The fragility of the materials I am handling. The letters are sometimes faded, ripped, stained by the rust of paperclips or the mottled brown of age. And the fragility of communication. Did a recipient comprehend the nuances of emotional or intellectual content of a letter’s message, both its overt and its occluded meanings? And then the fragility of my own powers of interpretation, can I hold my own assumptions in check and not be misled by my own frame of reference and experience? An object I came across in my first week of research brings to mind the fragility of the literary object as it continues its life beyond the metaphorical and literal death of the author (Richardson died in 1957). I chose not to carry my 4-volume edition of Pilgrimage across the Atlantic thinking I would pick up the copies available in the University of Texas Library. Pulling the ‘local’ edition off the library shelves I found in my hand the frankly hilarious Popular Library edition of Pilgrimage, printed in New York in 1976 (see attached photograph). Hilarious in the sense that the editorial packaging of the novels – a cover which connotes an altogether different genre (I will leave readers to make their own interpretation of what I mean here) and a description of Richardson’s dense experimental oeuvre as ‘a towering novel of female revolution’, coupled with Rebecca West’s exclamation ‘a miracle!’ – seems rather misguided to say the very least. One wonders what mid-1970s readers, aflame with second wave feminist awareness or other liberationary political understandings, thought they were about to encounter when they brought the book home, probably not the intricacies and challenges of stream-of-consciousness technique which greeted them on the first page and beyond. Richardson’s experimental modernist novels here seem so fragile in their mis-packaged state, so vulnerable to the torsions of advertising and the literary marketplace in a later twentieth-century decade at such a huge cultural remove from the early twentieth-century decades of their making. Pilgrimage undergoing its own pilgrimage after Richardson, and after modernism.

by Joanne Winning, September 2016

Dr Jo Winning