Photograph courtesy of Gilbert Mercier. All Right Reserved.

It’s not really the place of the conference organizer to declare the occasion a success or summarize its shortcomings. Which means I’m probably not the best person to reflect on the gathering of great and diverse minds on November 15 at Tulane University to discuss the ways in which the consequences of Hurricane Katrina are still shaping our understandings of the future of New Orleans – a future that is being called upon as a kind of ‘test case’ for the rest of the United States and the world.

But having now listened back over the rich and varied conversations that went on during that day, I’d like to do a little more than simply make the audios available online and slowly draw the material into my academic writing. In the first session of the conference, Nick Slie suggested that ‘in New Orleans we give you unconditional love first, make you earn it later’, an idea picked up by a number of people throughout the day. This article is a small offering to all of you who responded so positively to the invitation of a stranger and an outsider to give up your time and share your stories and insights.

This conference was for me the culmination of many conversations I’ve had with various people who have generously given their time to talk to me about their work in New Orleans over the last few years. By trade, and when I’m not teaching, I work with texts, not people, but my work on post-Katrina New Orleans has taught me that the life of a city cannot be found in books alone. This piece is offered not in the spirit of academic critique, which can often devolve into an unpleasant process of splitting hairs, but in the spirit of reflection and exchange: a spirit that animated a gathering which encompassed myriad and often conflicting viewpoints that, if not always in dialogue, somehow managed to exist respectfully and often provocatively in the same room. These are the narratives that emerged for me.

Richard Campanella: the failure of the levees

Richard Campanella’s keynote, ‘Disaster as Educator: Responses and Lessons in New Orleans, 1722-2012’, offered a whirlwind tour of 290 years of disaster history in this region. Campanella’s historical narrative told of fires, epidemics and hurricanes that repeatedly threatened to erase the young city from the map in the eighteenth century. It told of a nineteenth century New Orleans that was ‘remarkably resilient to its many disasters’. With the vast majority of the population living on higher ground and in higher density, with a landmass that had not yet sunk below sea level, the many floods and hurricanes that battered the city in this century did not lead to major catastrophe as we saw in 2005.

The collapse of the levees and subsequently all urban systems that occurred following Katrina can partly be blamed on the disastrous ‘levees only’ approach adopted in the early part of the twentieth century and shaped by military-trained engineers who saw the river as an enemy as opposed to something to be managed and even accommodated. Deprived of the ability to deposit the sediment that builds the land, the Mississippi River and its many tributaries, as Campanella explained, then threatened ‘to create a mega-catastrophe every 50 years rather than small disasters every couple of years’.

The lull in hurricane activity that opened up in the 1970s and 80s gave way to ‘an unfurling social disaster’ of white flight and middle class exodus to the suburbs, leaving the inner cities deprived of a tax base and the basic infrastructure necessary for people to prosper. ‘The theme here,’ Campanella explained, ‘is that slow subtle social forces have a greater impact, at least in our case, on the city’s destiny, than epic disasters.’

Kalamu ya Salaam: ‘the levees did not fail’

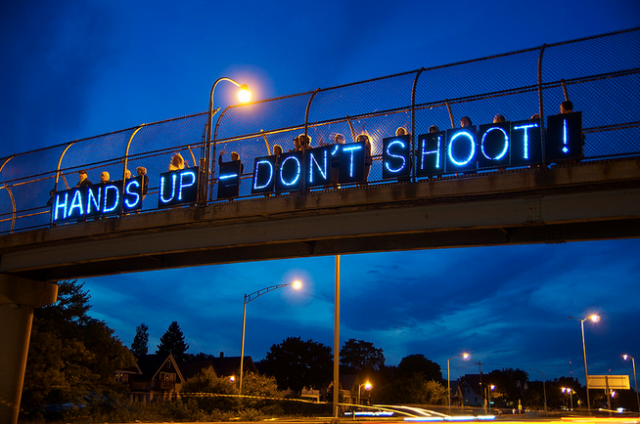

Social disaster was a theme that punctuated Kalamu ya Salaam’s keynote, which addressed not racialized poverty as it developed in the 70s and 80s but rather the grotesque inequalities that have animated the process that has not felt like recovery to many who suffered Katrina. Addressing ‘fellow New Orleanians’, paraphrasing Frederick Douglass and taking the occasion to task, Salaam distanced himself from what he implied was a ‘celebration of a new metropolis rising from the ashes and debris of an old and inundated city’. As the title of his talk powerfully put it: ‘What to us Negroes is your “New” New Orleans?’

Salaam’s talk similarly focused on disastrous environmental decision-making – in particular, the construction of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet – that exposed vast numbers of people to harm’s way. ‘This is a massive failure at all levels of government from city, to parish, to state, to federal government,’ he reflected. ‘Or is it?’ This is where Salaam’s talk decisively departed from Campanella’s themes.

‘Perhaps this is not a failure but instead is the very real intentions. The motherfuckers were trying to kill us.’ This last note led Salaam back to slavery’s middle passage to consider the distance between the origins of black America and the contemporary Lower Ninth Ward. Contemplating the destruction of the natural wilderness in the Lower Ninth as well as the painstakingly slow redevelopment since Katrina, Salaam asked: ‘Is it any wonder I do not celebrate the redevelopment of New Orleans? What do I, a child of Lower Nine, have to celebrate?’

I don’t want to live anywhere where they have

tried to kill us even if it was once a place

I called home—but still and all, my bones

don’t cotton to Boston, I can’t breath

that thinness they call air in Colorado,

a Minnesota snow angel don’t mean shit

to me, and still and all, even with all of that,

all the many complaints that taint my

appreciation of charity, help and shelter,

even though I know there is no turning back

to drier times, still, as still as a fan when

the man done cut the ‘lectric off, still,

regardless of how much I hate the taste

of bland food, still, I may never go back,

not to live, maybe for a used to be

visit, like how every now and then you

go by a graveyard…

As Joel Dinerstein, who was chairing the session, pointed out, the theme here was sacrifice: ‘What is life without a home?’ But this isn’t just any home, as Salaam’s lines imply – a sentiment that was echoed throughout the conference. Salaam’s talk, which ranged across times and spaces, offering a critique of white supremacy and American democracy, was animated by the approximately 100,000 African Americans who have not been able to return home to New Orleans in Katrina’s aftermath; a city that prior to the storm boasted higher numbers of native born residents than almost any other major US city, meaning that it had nurtured some of the most close-knit African American communities in the nation – communities that gave birth to much of the culture for which New Orleans is famous.

The threat posed by Katrina to these communities and thus to New Orleans in general returns us to a theme of Campanella’s talk and the seductive post-Katrina metaphor of the blank slate; as Campanella put it:

This metaphor, the tabula rasa, wiping the slate clean, was erroneously applied after Katrina – completely erroneously – because 300 years of inscribing value into place and space, through the erection of a built environment, through emotional and social and economic ties, Katrina’s floodwaters couldn’t even come close to wiping the slate clean, despite that we use that metaphor over and over.

Nativism versus the newcomers

This metaphor of the blank slate seems particularly fitting and disturbing in the New Orleans context. Aspects of mainstream US mythology have so embraced the idea of the ‘blank slate’ – with its somewhat contradictory connotations of wiping the slate clean of Old World corruption and tyranny, and the fantasy of empty lands to be colonized (with its logic of subjugation which is anything but the repudiation of oppression); hence the mythic level playing field is subverted by hierarchies in the first instance. New Orleans, on the other hand, is often said to have partially resisted the processes of ‘Americanization’ due to its stubborn attachments to Old World connections – European and African – which defy the model provided by the ‘blank slate’. As Linetta Gilbert pointed out in the last session, the maintenance of some of these connections, particularly to outmoded European forms of governance, has meant that the city has often been ruled by a corrupt oligarchy; but some scholars have also suggested that central to ‘Americanization’ is the black/white binary, which clearly deeply marks the New Orleans landscape, but perhaps not deeply enough to disable those cultures of resistance that are arguably best understood as indigenous.

It is this discourse of indigeneity that has fascinated me ever since I arrived in New Orleans in September, and which ran beneath the surface of so many of the conversations at the conference, including Salaam’s keynote and much of Campanella’s scholarship on the city. Hannah Kreiger-Benson was not the only participant keen to acknowledge that her moving to New Orleans in 2007 meant that ‘I speak from that experience, and only that experience’. So many of the day’s introductions involved the telling of ‘Katrina stories’: personal narratives that situated the participants in relation to this now all-important temporal division alongside their spatial coordinates vis-a-vis New Orleans.

Residing in the city prior to Katrina did not necessarily mean native status – according to the 2000 census the city boasted a native born population of 77% and it is notoriously attached to the idea of nativity: long-time residents not born in New Orleans rarely escape being known as a ‘transplant’. But pre-Katrina residency did mean that you were not part of the post-storm influx of newcomers who have come to be associated with the processes of gentrification – an issue first raised by Catherine Michna who was chairing the first session – that have marked the city’s reconstruction.

The post-Katrina success story: success for whom?

As Nick Slie put it in response to Michna’s suggestions, ‘a lot of people are now in New Orleans living ahistorical lives’. Slie illustrated this idea by referring to the ‘progress train’ that he imagined running through the post-storm city, and which in turn gestures to the notion that the change that the storm brought is both positive and, perhaps, I think, all-American: the national narrative of progress is one that has not been fully extended to a city that resides on the margins of the nation’s imaginary. New Orleans’ long cultural memory has historically, it could be argued, subverted the amnesia of a future-bound national culture. But it is precisely this memory that is under threat: ‘You can live with the progress now, and you can just jump right on the progress train and do your art and whatever it is you’re doing, but you don’t have to sit in the deep 100 year history of people’s families, where they came from.’

Slie’s comments come in response to the narrative often spun by the media that the ‘success story’ that the post-Katrina city has become known for is partly due to the influx of young, often highly educated entrepreneurs who have boosted the New Orleans economy. As a number of people suggested, this doesn’t mean much to the 53% of unemployed African American men who live in the city. Neither does it take into account the fact that what so many see as under threat in post-Katrina New Orleans are cultures and values that notably transcend the market.

The paradox of gentrification: New Orleans culture and market values

Brice Miller’s contributions to the last session on post-Katrina futures captured the complicated and thorny nature of a debate that is often over-simplified by the all-encompassing and divisive – though necessary and inevitable – term, ‘gentrification’: ‘I’m a native of New Orleans, born and raised, son of a jazz musician … the indigenous cultures of the city are very relevant to who I am as a person… this culture is being celebrated and attacked by the exact same people.’ Miller elaborated: ‘If it wasn’t for the music and the culture, New Orleans would just be another bland place and nobody would be interested in it. It’s important that we understand the culture is much more than just a profiteering system, that it’s a way of life for people.’ For Miller, the post-Katrina push towards regulation has endangered the musical cultures that draw newcomers who often then become part of the system that threatens these same cultures.

While this makes no sense in economic terms by threatening what is arguably the tourist trade’s most valuable commodity, it is perhaps the logic of economics that needs to be marginalized: as Ron Bechet suggested in the first session, ‘art and culture is a manifestation of the people, and when we try to commodify it is where we run into problems, and I think that’s some of what’s happening here.’ The commodification of art in the city is perhaps the corollary of other public spaces that have, in Katrina’s aftermath, been transformed by the logic of privatization and the market.

‘A crisis is a terrible thing to waste’

The idea that the post-Katrina city has become a kind of laboratory for neoliberal engineering is fairly well-known: Naomi Klein noted these patterns in her 2007 book Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, which documented what Klein saw as the dismantling of the public sphere in post-Katrina New Orleans. The demolition of public housing that occurred in Katrina’s wake was interpreted by many as a cynical move on the part of authorities that had long wanted to remove supposedly ‘blighted’ projects from prime real estate. As Lawrence Powell, Tulane historian who spent the earlier part of his career working in public housing, suggested in the last session, it was clear to him that ‘as soon as the city could figure out a way to get rid of them [public housing residents], they would. Katrina was a classic example of “a crisis is a terrible thing to waste.”’ Powell elaborated: ‘Nobody wants to reconstitute those challenged communities as they were, but it’s a terrible, tragic thing, to push people out of their homes, whose families maybe have been in this city for eight generations.’ A similar story might be told about the closure of Charity Hospital and the sacking of thousands of public school teachers after Katrina to make way for Charter schools.

Noise ordinances are one example of the attempt to drive from the public sphere musical cultures that have long ‘bubbled up’ from the streets in the city. The increasing reliance on non-profits as a way of funding the arts is possibly another. See the discussion here. And yet art also, as many pointed out, should represent and imagine alternatives. The first panel on ‘Art after Katrina’ provided a number of examples of people engaged in projects that have been rejuvenated as a consequence of the storm.

As Carol Bebelle, founder and director of the Ashé Cultural Arts Center, explained, after the storm ‘Ashé’s light became like a beacon when New Orleans’ lights went off’. It became a nerve centre for the community arts scene in Central City, and occasioned the realization of a vision that had not taken off before Katrina. Bebelle summarized Ashé’s central goals: ‘culture and art and equity … and learning from a past that’s not done well by everyone.’ She elaborated: ‘Artists have always been trash to treasure people. You give them nothing and they make something out of it… And so to create a landscape where that’s possible is really what I would say, from the Ashé philosophy, is what we’re reaching for.’ But Slie’s comment on his own work with Mondo Bizarro seemed to apply here too: ‘its an approaching, it’s not an arrival.’

Rebecca Mwase continued this theme. She is one of the many actors and theatre-makers who arrived in New Orleans after Katrina. As Mwase suggested, ‘one thing that I’ve continually reminded myself of since I moved here after Katrina is that I know less than I think I know and I’m always aware and curious about the stories that I don’t know yet.’ For her, the ‘post-Katrina art scene is about: How can I listen more?’

Art and activism: overcoming the distinction?

The concept of community engaged art to which many of the participants are committed in many respects overcomes the distinction between art and activism that the conference structure partially and somewhat arbitrarily maintained – as was pointed out by Helen Regis who chaired the panel on ‘Activism and Organizing after the Storm’. Abram Himelstein’s Neighborhood Story Project, which he describes as ‘collaborative ethnography …an experiment in reclaiming stories’, is one of the clearest illustrations of the ways in which the control of narrative in the post-Katrina city is directly related to power and the ways that the city has been and is still being re-shaped. Luisa Dantas’ Land of Opportunity feature documentary film and larger interactive website is another: as Dantas explained in the last session, her project’s aim has been to listen to and represent the ‘competing visions of what the future of New Orleans should be, and the different agendas that come into play’.Other art projects like The Porch by Bechet and Willie Birch and the numerous theatre projects produced by Mondo and Artspot Productions similarly centralize the importance of storytelling to the life of the community.

Community organizing emphasizes the more directly political aspects of storytelling to citizen participation. Jordan Shannon’s work with Puentes and New Orleans’ Latino community, Darryl Malek-Wiley’s work with the Sierra Club and the Lower Ninth Ward, Kreiger-Benson’s work with MACCNO (Music and Culture Coalition of New Orleans) and New Orleans musicians and Timolynn Sams’ work with the Neighborhoods Partnership Network is all about advocating on behalf of particular communities whose voices have been marginalized or invisible in the decision-making processes that have had such a huge impact on people’s lives after the storm. As Gilbert reflected in the last panel, looking back on her work with public housing, the Ford Foundation, and now Declaration Initiative, ‘policy has to really have meaning for the people who will benefit from it’; and the only way for this to happen is for communities to have a real voice. This is what Sams describes as the Sesame Street methodology: ‘that every person, regardless of what they look like, how they sound, who they represent, is part of the community’s fabric.’

Unfortunately the Sesame Street methodology has not been followed by many of the most influential actors in the city’s reconstruction. As Greer Mendy put it in the first panel, ‘the race and class issue, it slams you, across the face, front and back’. Mendy’s work with the Tekrema Center for Art and Culture located in the Lower Ninth Ward is very aware of the limited funds for community art projects that don’t want to sacrifice their agenda to partner with commercial concerns. ‘Art is a luxury,’ she explained, ‘unless it’s free.’ For her, the agenda has to be about ‘livability’, about survival – an activity that should not be reduced to the dynamics of the marketplace but which has ultimately never been able to disentangle itself from economic imperatives.

The future in a ‘post-survival’ New Orleans

Louisiana’s disappearing wetlands

Linetta Gilbert concluded her contributions to the Post-Katrina Futures panel by stating: ‘I don’t want to believe that you have to be poor and broken to create the blues or create jazz. I want to know that you can play that horn even living in a house that doesn’t leak; that your message is not shaped by your circumstances only … I don’t want the message to go out – that in order to keep the culture of New Orleans that people have to be broken down, disenfranchised and in a bad way to tell their story.’

While so much of the conference was devoted to describing the wrong turns taken by the recovery and reconstruction process, and the various ways in which these turns have been resisted, the last panel in particular addressed the challenge posed by Nghana Lewis, who chaired the session, that New Orleans throughout its history has been absorbing various forms of change; with the implication that the change brought by Katrina should perhaps not be uniformly treated as an ‘unnatural’ distortion of the city’s ‘proper’ evolution. This suggestion also seemed to animate Campanella’s observation that after Katrina people tended to resist change and crave normalcy. Gilbert’s desire to realistically assess pre-Katrina New Orleans, and to discard what she constructed as the romanticization of poverty, proposed one way of coming to terms with aspects of the ‘new’ New Orleans.

The ways in which the reconfigured city has exacerbated often racialized inequalities led Himelstein to state: ‘I don’t experience the rebuild as a total success… I’m not living in the city that I wanted, and I didn’t necessarily fight all the fights I wanted to fight in the last eight years.’ Echoing Salaam’s keynote and some of Himelstein’s disappointment, Malek-Wiley described a Lower Ninth Ward being slowly redeveloped by citizens whose determination, commitment and work is under the government radar and beyond their concern: ‘it’s a jungle down there.’ Willie Birch sounded this note of unease about the future of the city’s culture repeatedly from the audience.

And yet all conceded that there was value in some of the newness, with Malek-Wiley embracing the levels of post-storm volunteerism as ‘amazing’. Recalling the Saul Alinsky model, Himelstein said of the post-Katrina newcomers: ‘its really about whether this relationship is going to be permanent, it’s about whether or not I should invest in being close to you … I don’t have the energy to greet all the people who come with good intentions and tell them my stories … I just want to be here with those people who are going to stay here.’

This sense of the need for continuity and perseverance in the fight for social justice strongly animated Sams’ and Shannon’s contributions. Sams suggested that if communities in New Orleans continued to see their efforts at change-making as atomized ‘campaigns’ as opposed to a larger ‘movement’, ‘we will win some battles but the war will be lost’. Shannon’s theme was similar, when she referred to the Congress of Day Laborers’ recent and unexpected victory against discriminatory immigration policies and suggested: ‘I think we can sell our communities short and go after what we think we can win, instead of what justice looks like, and this was something that actually went after justice and got it.’

The idea that we need to look at the bigger picture and play a long game, one that isn’t just about reactive campaigning in what feels like an emergency situation, seemed to inform Amber Wiley’s suggestion that what we are now dealing with is a ‘post-post-Katrina New Orleans; we’re not in the post-Katrina era anymore.’ Wiley’s own work as an urban historian and teacher of students of architecture – who, she explained, view themselves as the planners of the future – encapsulates the tension between the past and future but also suggests that the need to reflect on and preserve the past must not stand in the future’s way.

Miller’s related suggestion that this new ‘post-post-Katrina’ space might be described as ‘post-survival’ pointed to a new frame for a New Orleans in which Katrina is at least decentred as a reference point. Certainly when I began to organize this conference I heard a lot about ‘Katrina fatigue’, though everywhere there is evidence that the city has yet to move on.

It strikes me that there is much value in thinking of ‘post-survival New Orleans’ in a comparative vein that both acknowledges New Orleans’ distinctiveness and recognizes that the experience of Katrina-like catastrophes is not unique. Dantas’ work, which has begun to compare the Katrina story with that engendered by Hurricane Sandy, provides a necessary reminder that disaster situations only highlight forms of social abandonment that already existed as ‘slow violence’. The comparison is also a reminder that disasters are not social levellers but rather exacerbate inequalities. In this sense the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of Katrina merely provides one vantage point among many to view the city’s evolution; its ‘unfurling social disaster’ and its rich material culture, the one which cries out for amelioration and the other that calls for preservation.

Postscript: New Orleans and the transnational

It also strikes me that another way of envisaging ‘post-survival New Orleans’ is to open it up to comparisons with the rest of the world. The title of a conference is only ever a provocation, and it struck me as very interesting that it was the future of New Orleans, and not transnational perspectives, that took centre stage. A number of people have suggested to me over the last few months that New Orleans is like a magnet that draws you in: the local often proves so compelling that you have to defeat irresistible centripetal forces to gain perspective on the rest of the world. Initially this surprised me: this city had always seemed to me to be so open to its outsides, so clearly marked by the African and European influences that represent its most prominent anterior worlds. But this unexpected suggestion now seems right to me. The deep roots that mark the lives of so many that live here, and which were so violently displaced after Katrina, are about stability and place, values that don’t sit well with the mobility implied by the transnational.

And yet, as Carol Bebelle suggested to me a couple of weeks after the conference, the daily rituals that celebrate the value of this place are deeply marked by African and Caribbean ancestors that live on in the city. Some have argued that New Orleans’ status as America’s most ‘African’ city partially accounts for the appalling treatment of evacuees after the storm.

New Orleans as a Caribbean city?

My own work is currently trying to make sense of some of this by thinking about the connections between post-Katrina New Orleans and post-earthquake Haiti. These connections go beyond the rhetorical violence done to both sets of victims, but arguably this shared suffering is in part constituted by this ‘beyond’: after the Haitian revolution at the turn of the nineteenth century the New Orleans population doubled in size as a consequence of the influx of ‘refugees’ – slave owners, slaves, and free persons of colour – from the former slave colony of Saint Domingue. These newcomers arguably had a profound effect not only on New Orleans culture and its unique racial make-up in the context of the United States, but also on the perception of New Orleans’ distinctiveness and, by some, often negative, accounts, ‘foreignness’.

New Orleans’ status as a ‘Caribbean city’ did not go unmarked at the conference. Jordan Shannon mentioned that while teaching Latin American Studies at Tulane, ‘I would continually stress to students that we can look to Latin America not only as a source of dictatorial government or poverty, but because people have been combatting forms of oppression and postcolonial structures – that are actually very similar to New Orleans – we can look to these places as innovative sources of solutions’ including cooperatives and other social movements. Certainly the celebration of the public sphere that seems so evident in New Orleans has much in common with these kinds of collectives. Hannah Kreiger-Benson agreed that the Latin American model provided ‘a really fascinating commentary on the city and the way it’s situated in America and also in the Caribbean’.

The conference’s title was in part an invitation to reconceptualize New Orleans’ geographical location, as not only part of a larger Gulf South but also a larger Caribbean eco-system and African and European political ecology. New Orleans absolutely is part of the United States, but paradoxically its own – vexed – exceptional status within the nation might be seen as a gateway for thinking beyond the limitations of US exceptionalism; perhaps beyond the logic of national or regional exception in general.

Some final thoughts from Mexico

Mexico City’s wonky angles

I began writing this piece in New Orleans and continued writing as I travelled to Mexico City. I was fascinated to discover another sinking cultural gem that was also the result of an attempt by human beings to triumph over water and this time build on top of the site of a lake. Campanella’s description of the dangers of the ‘levees only’ approach and Malek-Wiley’s reports on conversations about sustainability in the Lower Ninth Ward seemed to apply here in this smog of pollution and water and cultural productivity. Mexico City is hemmed in between mountain ranges which trap the pollution and create a bowl effect reminiscent of that which surrounds New Orleans. Also the result of the colonial imagination, the site of this city seems even more unlikely, when you witness the stunning Spanish architecture subside, at various rates – creating an uneven, jostling effect – across the city and particularly in its historic centre. The dilemmas described by Campanella in Bienville’s Dilemma (2008) haunt this city too, posing contemporary challenges about land and water use and adaptation to inevitable environmental effects that will have a profound impact on the city and its future ‘livability’.

Cultural connections were even more pronounced when I arrived in Merida, the capital of the tropical Yucatan, one of New Orleans’ sister cities and located just off the opposite shore of the Gulf of Mexico. Merida, like Port au Prince, is architecturally reminiscent of New Orleans and, in turn, Havana. It boasts a high percentage of indigenous peoples – some say about 60% – who are proud of their distinctive culture and cuisine, eager to preserve their practices against a seemingly encroaching dominant Mexican culture. The culture here contrasts with that of New Orleans in marked ways, but the city’s embattled status, and the sense of abandonment that stalks some of the beautiful Spanish and French colonial buildings at the city’s core – despite the fact that Merida, unlike New Orleans, is often promoted as a social and economic success story – is a reminder of the fact that so much of what seems to be unique to New Orleans are cultural traditions shared not just with the rest of the US but with its Latin and Caribbean neighbours.

-

This is not to say that New Orleans’ development has not taken these traditions on a unique course, but what the conference seemed to suggest is that the city is a case study of disasters of all kinds – that transcend the Katrina moment – which have miraculously co-existed with astonishing levels of cultural creativity that have much to teach the world. That these two legacies are possibly inextricably intertwined was suggested by Lawrence Powell when he said, ‘New Orleans to me is like a low grade fever, once it gets into the bloodstream it’s really hard to shake it, for all its problems’; and yet there also seemed to be a collective sense that ‘the rhythm of the community and the brilliance of the people’ that so struck Linetta Gilbert after spending some time in the city is currently endangered by ongoing economic, social and environmental disaster that must be averted if New Orleans culture is to thrive.

Thank you

Finally, I would like to thank everybody for coming to join the conversation, and particularly the speakers and panellists: Richard Campanella, Kalamu ya Salaam, Carol Bebelle, Ron Bechet, Luisa Dantas, Joel Dinerstein, Linetta Gilbert, Abram Himelstein, Hannah Kreiger-Benson, Nghana Lewis, Darryl Malek-Wiley, Greer Mendy, Catherine Michna, Brice Miller, Rebecca Mwase, Lawrence Powell, Helen Regis, Timolynn Sams, Jordan Shannon, Nick Slie, Amber Wiley. It was a privilege to work with you all.