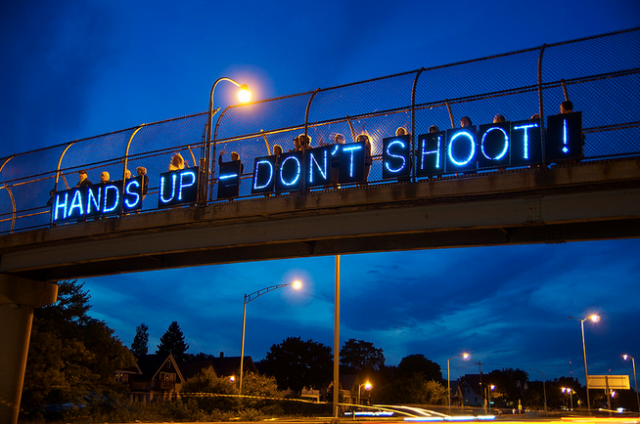

As #BlackLivesMatter continues to trend on twitter in the wake of events in Ferguson and the police shootings of countless unarmed black men across the US, a major experiment in urban education is quietly transforming the nation’s schools. These reforms are occurring in the name of severing the so-called ‘school-to-prison’ pipeline that has made so many young black Americans the target of the criminal justice system. Where events in Ferguson have brutally recalled the unfinished business of the civil rights movement that left the majority of African Americans socially and economically disenfranchised, this new school movement sees itself as heir to that transformative moment in the 1960s, aiming to deliver social mobility to America’s most marginalized populations.

Given the grand ambitions of these schools, the view from inside is unexpectedly oppressive and confining. In what have come to be known as ‘no excuses’ schools, children are frequently asked to walk on demarcated lines in corridors, observe silent lunches, and adhere to a strict disciplinary code. Many employ shaming rituals for so-called misbehaviour, and require students to track teachers with their eyes. The emphasis is strictly on ‘academics’, meaning language and maths, on which students are constantly tested. ‘Teaching to the test’ not only pushes the arts and physical education to the margins of the curriculum, but emphasizes rote learning and discourages dwelling on ambiguity that drives creative and critical thinking. Most strikingly, given the integrationist aspirations of at least the early stages of the 1960s black freedom movement, these schools are overwhelmingly populated by African American kids.

‘No excuses’ is not a formal label but a mantra invoked by these schools to suggest that they have ‘no excuse’ not to close the ‘achievement gap’ between black and white children, ‘no excuse’ not to graduate successful college entrants. The enormous pressure placed on teachers by these schools is reflected back on the students who are subjected to measures that many observers characterize as not just authoritarian but excessive and cruel.

‘No excuses’ has become shorthand for a subset of schools in the charter school movement that has swept the United States since they gained cross-party support in the 1990s. Similar to the euphemistically named ‘free schools’ in the UK, charters are publicly funded schools largely free from ‘government interference’ and are run by non-profit entities or private enterprise. Calls in the 1960s for the decentralization of schools initially came from parents and teachers seeking more local control, and were later hijacked by the language of ‘choice’ and the norms and values of the market.

Officially, the ‘school choice’ that charters claim to offer is encapsulated in a parents’ right to withdraw a child from a school at any moment, supposedly making these schools more ‘accountable’ to parents who can contemplate a marketplace of schools rather than putting up with failing neighbourhood schools. In reality, school choice has constituted widespread selection practices on the part of the schools that aspire to teach privileged sections of the population. In many urban areas, this has led to a two-tier system where some schools are left to educate those unable to meet a string of selection requirements apparently designed to exclude poorer students.

Charter operators like the pioneering Knowledge is Power Program, KIPP, have stepped into this gap in the market with an open-enrolment policy and the ‘no excuses’ brand, designed for survival in a system that closes supposedly ‘failing schools’ as soon as test scores fall below the mark. The ‘no excuses’ ethos fosters a highly controlled environment in which children are force-fed information for tests, the generally favourable results of which, a number of studies suggest, are subject to widespread manipulation. This system of ruthless competition has arguably reintroduced the principle of racially segregated learning via the backdoor.

As Sarah Carr’s work on ‘no excuses’ charter schools in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans shows, the foundations that often partially fund these schools ‘so view their mission as educating poor, minority children that they do not provide philanthropic support for schools with significant white or middle-class populations’, meaning that some charter operators are incentivized to ensure that their schools remain some of the most racially segregated in the nation.

After Katrina, New Orleans became the epicentre of the charter school movement when the Orleans Parish School Board undertook the mass firing of 7,500 public school workers, most of whom were African American. In the meantime, rules for the creation of charter schools were relaxed, leading to the rapid emergence of a string of charter schools largely staffed by Teach for America recruits – non-unionized, predominantly white, ‘fresh faced’ graduates, many of whom, initially at least, come from Ivy League universities. Encouraged to view their students as ‘blank slates’ where ‘data’ might be banked, these inexperienced recruits – who receive about five weeks training – are expected to solve the problems of racialized poverty in these urban education laboratories, while students are asked to leave their poverty, their hunger and their histories outside the classroom. This is a strikingly different approach to the one that still governs teaching practices in predominantly middle class schools – where personal agency and the arts are still deemed important tools for social empowerment.

New Orleans parent advocate Ashana Bigard suggests that the philosophy behind these schools is that ‘poor black traumatized children apparently have different brains, alien brains, that we cannot educate the same as middle class white kids.’ Bigard argues that these schools – that emphasize not independence and assertion but submission to authority – are not educating black children but ‘conditioning them for low-wage jobs.’ Or prison.

I had the privilege of meeting and talking with Ashana Bigard in October 2014. She told me that while working with an organization representing the families of incarcerated children, she was asked to identify at what point most of these kids were entering the criminal justice system. Ashana explained that on examining these figures for New Orleans in 2008, her jaw dropped as she realized that most children were going directly from schools. Against the conventional wisdom that says that keeping poor kids in school and off the streets is the best way of avoiding jail, in fact, as Ashana puts it, ‘your kid who is cutting school is a hell of a lot safer than if he’s in school every day.’ Where the commonplace of, for example, two eight-year-olds getting into a fist fight in the classroom would have formerly received an in-house response, now teachers routinely call the police and involve a criminal judge. ‘The same eight-year-old is going to be handcuffed, put in a police van, gain a record of some kind, and could be expelled.’

The militarization of US schools has gone hand in hand with corporate penetration and the rollback of state welfare that has had such a devastating effect on African American communities, already suffering the results of systemic racism, all over the US. Just as militarized policing has become the norm in neighbourhoods from Ferguson to Detroit, public schools that resemble prisons have proliferated in urban areas across the country.

Ashana tells the story of one six-year old boy put before a criminal judge for bringing into school rolaids, common antacids, under the mistaken belief that they were candy. This child was charged with possession and distribution of drugs and sent to an ‘alternative school’, commonly viewed as a warehouse for prison. It took Ashana and her co-workers five months to get this child back into his regular school, by which time he was too frightened to even take a pen into class.

The first time I visited New Orleans after Katrina was in April 2008. This was two and a half years after Katrina: many neighbourhoods had not yet been cleared of storm debris, while at the same moment the authorities started pulling down the city’s public housing projects. These scenes of demolition jarred sharply with the large homeless encampments that could be seen gathered on the Claiborne neutral ground under the shadow of the 1-10 overpass, and in other parts of the city. At the same time, I was invited into comfortable, air-conditioned offices by various non-profit entities and learned that these scenes of destruction were in fact part of a ‘benevolent’ project to ‘cleanse’ the city of blight. The representatives I spoke to were as convinced by the rightness of their mission as are those who are turning many urban schools into segregated laboratories.

Back in 2008, the slogan ‘housing is a human right’ underscored by large groups of protestors betrayed the fact that the federal government in league with city authorities and non-profits were not in fact doing public housing residents any favours. These residents, who had spent years demanding that their homes be maintained rather than left to suffer ‘benign neglect,’ were vocal about their wish to return to their homes after Katrina. Unlike the thousands of houses that had been utterly destroyed by the storm and subsequent flooding, these structures had weathered Katrina remarkably well. Indeed, the ‘bricks’ – public housing projects – had long been seen as potential refuges during storms. These incongruous scenes of destruction, and the inspiring movement that gathered to oppose them, was my first tangible lesson in neoliberal reform and the ways in which it seeks to cannibalize dissent.

The minefield that is post-Katrina school reform has marked the last trip to New Orleans that I’ll undertake for this project. Against the backdrop of Ferguson, it is hard not to see these new schools as places that establish the idea that poor African American children are always already on the wrong side of the law. How do we square this with the view articulated by so many soon after the storm that the post-Katrina city could be the scene of the next major phase of the civil rights movement? I’ll leave the last word to Ashana:

One of the biggest barriers is public perception. Somewhere along the way the nonviolent resistance movement in the 1960s got told a different way. That Martin Luther King and everyone were being polite and non-violent. That’s not what the hell happened, but it’s what is put in the books. And so if I raise my voice or I’m passionate about it, I’m crazy about it, no one can listen to me. The destruction of my community, my city, and the lives of so many of the children in this city that I am from, I am damn passionate about. And yes I’m angry, I’m hurt, I’m distraught. And how could I not be. This I my city, it’s my daughter’s future. We’re being destroyed – you want me to be polite about that? No I’m not polite. Here’s the thing, I’m that angry black woman. You can’t be perceived as that, because then no one will constructively listen to what you have to say. So you must be calm. The problem with being calm is that you have to act like this is not a crisis.