Parmi les ouvrages en relief conservés dans les collections du Musée Valentin Haüy, il en est un qui mérite une attention particulière.[1] C’est un livre volumineux (34 x 24 x 7 cm) et, malgré son mauvais état actuel, son dos recouvert de précieux vélin prouve la valeur qui lui fut accordée. Quand on l’ouvre, une annotation manuscrite en noir (écriture des voyants) au revers de la couverture indique qu’il s’agit d’une Géographie de la France, écrite en 1832 par Monsieur Hayter en braille abrégé primitif ; le texte est illisible au brailliste d’aujourd’hui. Une ancienne fiche ajoute qu’il existait aussi une Géographie de l’Asie, et que les deux titres furent écrits “avec l’imprimerie mobile de Mr Hayter “.

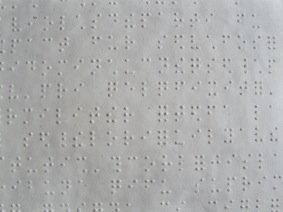

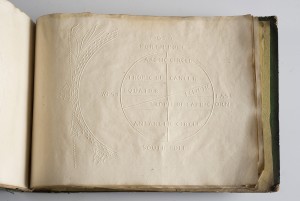

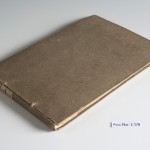

Edgard Guilbeau, fondateur en 1886 et premier conservateur, jusqu’en 1894, du Musée Valentin Haüy, explique que c’est Henry Hayter qui aurait rappelé à Louis Braille l’existence du w, lettre essentielle pour la langue anglaise[2]. Sinon, l’inventeur l’aurait oublié. Pourtant, le w existe en français, au moins depuis Charlemagne, pour écrire les mots d’origine anglo-saxonne. Considéré comme une lettre étrangère, il a longtemps été placé à la fin, comme dans l’alphabet braille originel.

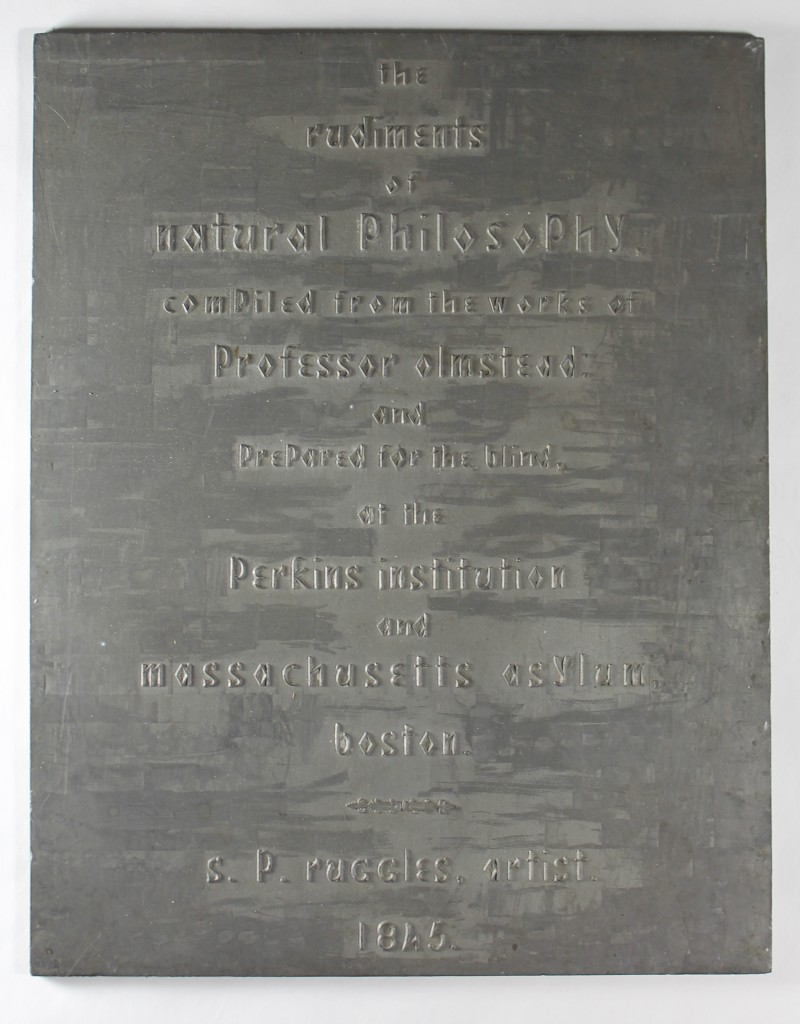

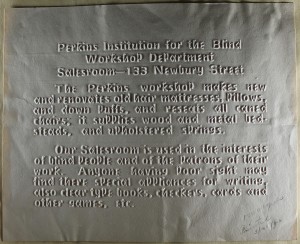

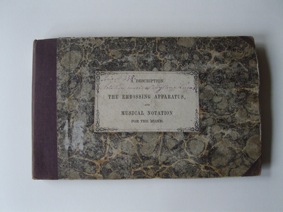

Front cover to ‘A Description of an Apparatus for Enabling the Blind to Emboss in Lucas’s Characters’. Credit: Association Valentin Haüy

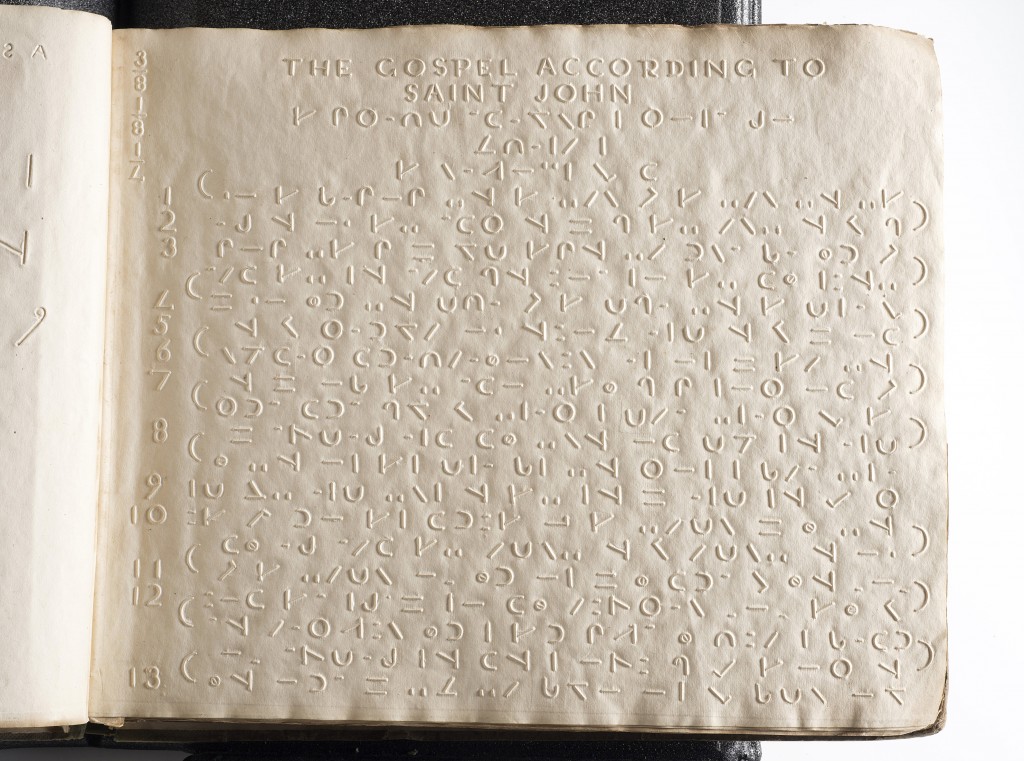

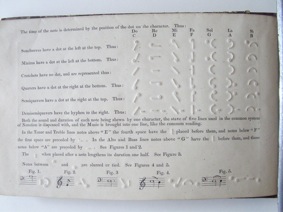

Le nom de Hayter est associé à un autre ouvrage des collections du musée. Il s’agit d’un petit livre (22 x 14 x 2 cm), dévolu à une notation musicale en système Lucas, une sténographie qui utilise des traits, droits ou courbes, des cercles et des traits combinés à des points.

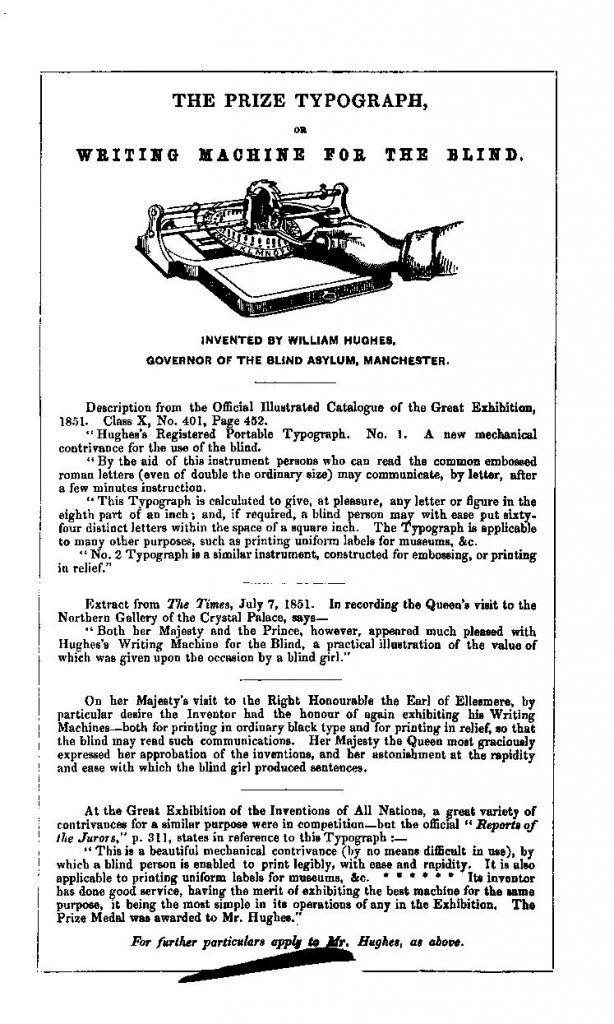

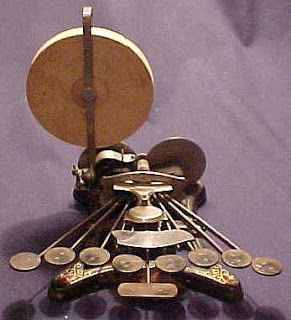

Frontispiece to ‘A Description of an Apparatus for Enabling the Blind to Emboss in Lucas’s Characters’. Credit: Association Valentin Haüy

A page from ‘A Description of an Apparatus for Enabling the Blind to Emboss in Lucas’s Characters’. Credit: Association Valentin Haüy

Au verso de la couverture, quelques lignes manuscrites en noir, qu’occulte partiellement une étiquette en braille ajoutée ultérieurement, nous permettent tout de même de lire le nom du propriétaire, Henry Hayter, l’indication « professeur de musique » et une adresse à Paris, rue de Vaugirard.

Henry Hayter (1814-1893) est le fils de Sir George Hayter, peintre anglais anobli en 1842 par la reine Victoria. Il est le troisième enfant, aveugle, d’un mariage de son père, à pas tout à fait dix-sept ans, avec Sarah Milton, qui en avait vingt-huit. Le couple se sépare deux ans après la naissance d’Henry[3]. Le jeune homme est élevé à l’Institution des jeunes aveugles de Paris.

Henry Hayter est aussi cité à la fin d’une lettre manuscrite en noir, dictée à un secrétaire par John Bird, aveugle, qui a tenu à la signer de sa main et à écrire lui-même le nom de son destinataire (malheureusement indéchiffrable):

[numéro illisible] Duke Street Grosvenor Square W.

Oct 4 h 1874

Dear [nom illisible]

Should you be able when in Paris to reach so far at the School for Blind Children situate I believe Rue de Sèvres, I will thank you to ask for M. Victor, if still alive and there, and should you find him there please to remind him that I visited the School frequently when in Paris 25 years since with John. At the Exhibition of 1851 in England I first learned from M. Foucault of the Quinze-Vingts that the Alphabet of M. Louis Braille was in general use in Paris, but that all mention of it was suppressed through M. Guadet’s influence, who wished that his own [mot illisible] system should have all the credit. I do not wish a large frame for writing Braille’s system, because I have the very one from which Mr Tomlinson had the sketch taken for the Wood cut for his Cyclopædia; but I will thank you to bring me one or two specimens of the smaller size to carry in the pocket, generally about 4 inches long sufficiently thick for strength, and about 1 inch wide, with two Rows of quadrangular holes corresponding to the three grooves below, or rather on the wood or metal below.

If you can also obtain a small specimen of the best kind of paper they have in use as well as 2 or 3 square inches of the “Cuivre jaune” M. Victor uses for making Stereotype-plates. Should you see him remember me kindly to M. Victor and to anyone else who may remember me.

I remain yours very truly

John Bird

PS: enquire if M. Hayter be still connected with the Institution. He is the son of the late Sir George Hayter who painted the Coronation of her Majesty and enquire also of M. Claude Montal and his daughter Clementine.

Front cover to ‘Cyclopaedia of Useful Arts and Manufactures, Mechanical and Chemical, Manufactures, Mining, and Engineering’, (1854), Credit: Association Valentin Haüy

Cette lettre est insérée dans une brochure appartenant au fonds de la bibliothèque patrimoniale Valentin Haüy, Cyclopædia of Useful Arts, celle-là même que cite John Bird. Un chapitre est consacré à l’imprimerie pour les aveugles. On y apprend que John Bird est allé sur le continent visiter différentes écoles spécialisées. Celui qu’il nomme « M. Victor » est Victor Laas d’Aguen. Il fait partie des élèves voyants que l’Institution de Paris intègre pour seconder les aveugles. En 1841, il devient surveillant des études et imagine, vers 1849, d’utiliser la stéréotypie pour l’impression du braille[4]. François Foucault est un ami de Louis Braille avec qui il conçoit en 1842 une machine pour écrire en noir avec des points[5]. Quant à Joseph Guadet, premier instituteur des garçons, puis chef de l’enseignement de l’Institution de Paris, il fonde en 1855 une revue pédagogique spécialisée, L’Instituteur des Aveugles, qui promeut l’usage du braille.

Un autre encart est ajouté dans la brochure à la suite de la lettre. C’est un article découpé dans le London Mirror du 19 février 1870, signé du même John Bird, intitulé « The Battle of the Types for the Blind ».

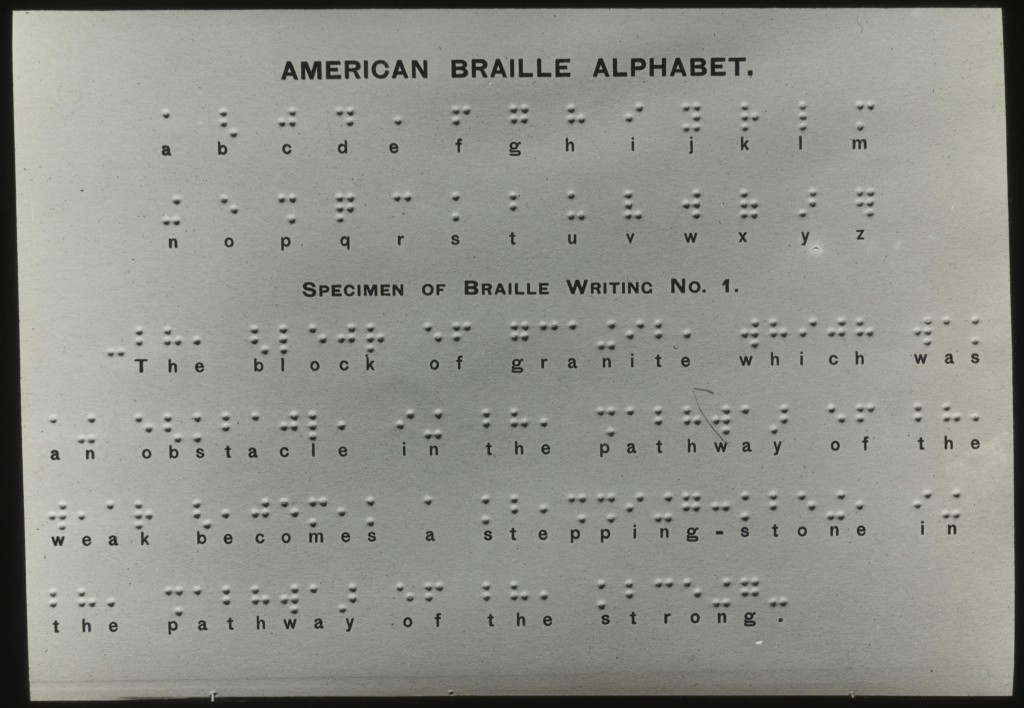

Il est utile de citer Henry Hayter dans cette histoire des systèmes qui se sont concurrencés, avant l’adoption franche et massive du braille, qu’illustre si bien Touching the Book. C’est un Anglais qui a imprimé le premier livre en braille, avec un matériel lui appartenant et très tôt après la publication du code braille. En 1832, Henry Hayter a dix-huit ans. Louis Braille en a vingt-trois, il a publié trois ans auparavant son Procédé pour écrire les paroles, la musique et le plain-chant au moyen de points et disposés pour eux. Cette première édition de 1829 comporte des signes qui combinent, non seulement des points, mais aussi des points et des traits, ainsi qu’un système sténographique. La seconde édition du Procédé, en 1837, propose encore quelques abréviations, mais abandonne les traits, insuffisamment perceptibles au doigt. La Géographie de la France comporte effectivement encore quelques uns de ces signes avec traits.

Ces documents témoignent de la constitution au XIXe siècle d’un réseau entre personnes aveugles qui outrepasse les frontières nationales et favorise la circulation des savoir et des savoir-faire. Ils prouvent surtout la détermination de ces personnes à s’approprier le braille.

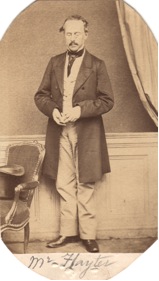

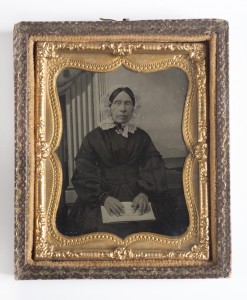

Le fonds iconographique du musée conserve un portrait en pied d’Henry Hayter. La photographie n’est pas datée. Elle a été prise dans un appartement bourgeois, à moins que ce ne soit un décor. Lambris d’appui au mur, tombé d’un grand rideau sur le côté droit, du côté gauche fauteuil cabriolet louis XV, sur l’assise duquel Hayter a posé son chapeau haut de forme. C’est un homme mûr qui a de la prestance. Il se tient droit sans raideur. Son visage est ovale, ses cheveux coiffés en arrière dégagent un front haut, les paupières sont baissées, il porte une fine moustache. Il est vêtu d’une élégante redingote, son pantalon et sa chemise sont clairs, son cou est entouré d’un foulard sombre formant cravate. Il tient dans ses mains à hauteur de ceinture un petit objet impossible à identifier, sur lequel il semble concentré : un poinçon à écrire le braille ?

Noëlle ROY

Conservatrice du musée Valentin Haüy

Responsable de la bibliothèque patrimoniale Valentin Haüy

Association Valentin Haüy

Au service des aveugles et des malvoyants

5 rue Duroc 75343 PARIS CEDEX 07

00 33 (0)1 44 49 27 27

[1] An English translation of this post is available here: Henry Hayter, Early Braillist by Noelle Roy

[2] Edgard Guilbeau, “La question du w dans l’alphabet braille”, Le Valentin Haüy, n°2, janvier-mars 1928, p. 37.

[4] Edgard Guilbeau, Histoire de l’Institution Nationale des Jeunes Aveugles, Paris, Belin Frères, 1907, p. 7.

[5] Zina Weygand, “Un clavier pour les aveugles ou le destin d’un inventeur, Pierre François Victor Foucault (1797-1871)”, Voir Barré (Périodique du Centre de recherche sur les aspects culturels de la vision – Ligue Braille, Bruxelles), n°23, décembre 2001, p.35