Birkbeck alum and Innovation Strategy Consultant Melina Padayachy identifies the essential missing link for successful entrepreneurs.

Finding ideas that markets would love can often seem like a feat that only few people are lucky enough to achieve. Study the stories of Amazon, Google and Starbucks for instance, and you would find that in each case, the innovators almost stumbled upon their ideas by chance.

Indeed, prior to the genesis of Google, Larry Page was a student at Stanford University where he was aspiring to download the internet on his computer and rank web pages based on their popularity. As a result, Google’s proprietary Page Ranking technology was born, making Google the leading search engine in the world.

For Amazon, Jeff Bezos came across an important piece of information about the exponential rise of the internet while researching opportunities for his boss and as a consequence, he created what is now the leading online retailer in the world.

Next, the idea to sell espresso in a coffee bar popped into Howard Shultz’s mind while he was attending a conference in Milan and he saw espresso bars at nearly every road corner. He wanted to import the concept to the United States and today, Starbucks is one of the leading coffee places in the world.

In all three cases, it would seem that the innovators were either in the right place at the right time or they were trying to solve the right problem. As a result, one may be tempted to conclude that innovation is essentially serendipitous and that any attempt to decode it would be futile.

Yet, if you examine how past innovations impacted their markets, you would find certain distinctive patterns that could be emulated. For instance, some innovations capitalised on existing trends while others were caused by growing and changing trends, and still others, created new trends.

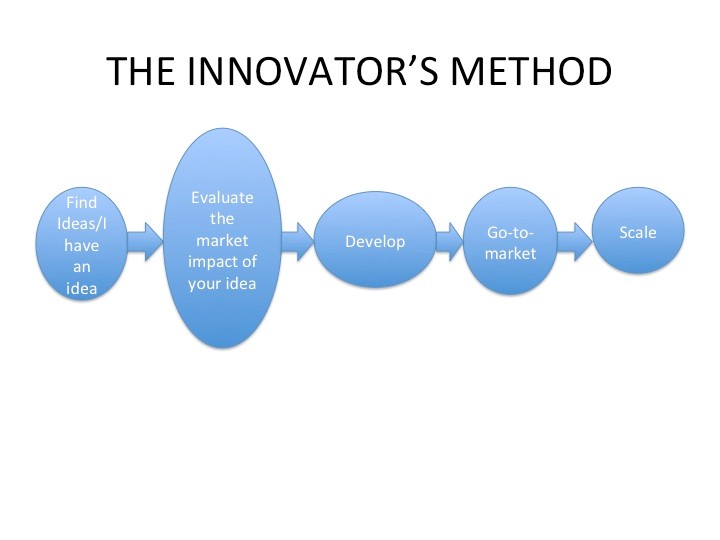

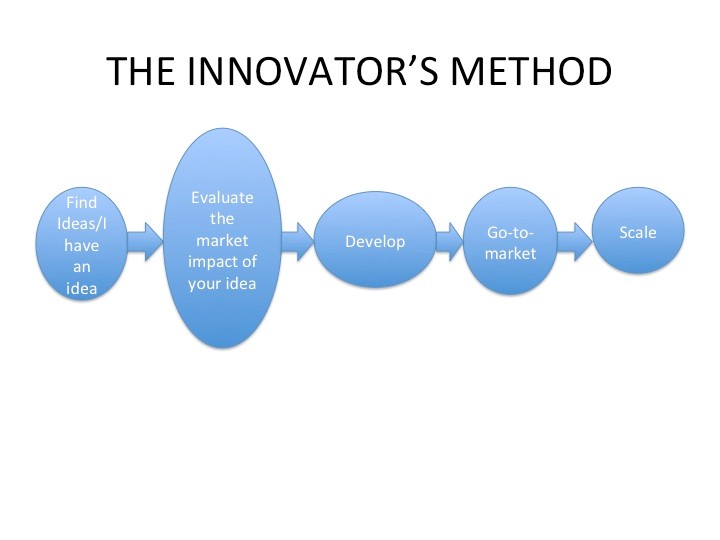

Of even more significance, are the facts that based on their respective market impacts, different ideas would need different development, go-to-market and scaling strategies.

The implications are quite significant because often, new ideas are subsumed under the generic banner of innovation and no distinction is made among their respective market impacts. As a result, some fail to take off. Indeed, scroll through the post-mortems of failed ideas and you would see that often, ideas failed because their market impact was either wrongly framed or overlooked, and as a result, the wrong development and go-to-market strategies were applied.

The Link between the market impact of an idea and its development strategies

Amazon.com

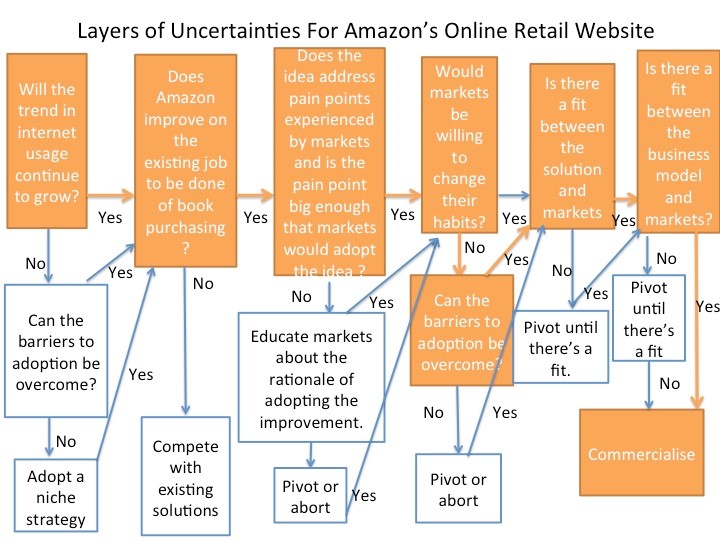

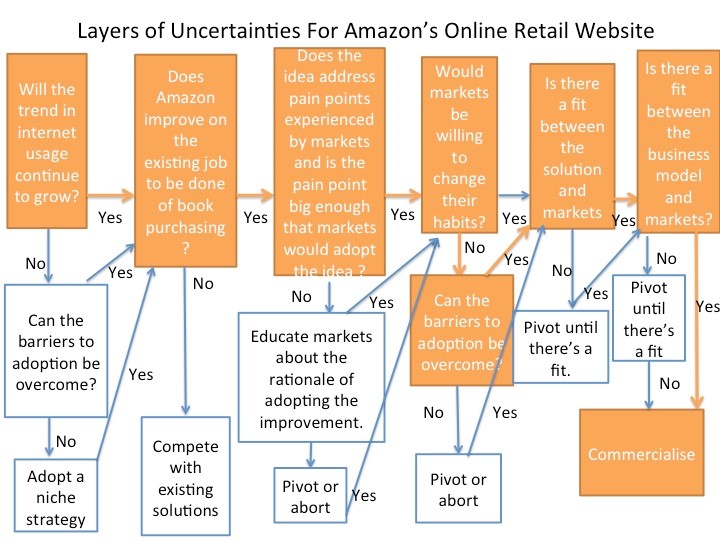

Take a look at Amazon.com for instance. In 1994, Jeff Bezos spotted a growing trend in the use of the internet and he noticed it was starting to change the way that books were bought. Internet technology was new at the time and people had just started buying books online. Already cognizant of the facts that internet usage was growing at the rate of 2300% per year and that books were the most sold items on the internet, Bezos decided to launch an online bookstore. However, the uncertainties facing the company were quite high.

To start with, it wasn’t clear whether book buyers would continue adopting the internet and if so, whether they would change their book purchasing habits. In that respect, Amazon relied on market intelligence to gauge the rate at which internet usage was growing.

Also, by observing markets, Jeff Bezos could find that there were already two online booksellers and that the market was growing.

Then, Amazon’s beta test prior to its launch helped identify the barriers to adoption, namely customers’ concerns about storing their credit card information online. Amazon thus came up with a secure credit card system. Incidentally, the company “finished 1996, its first full year in business with net sales of $ 15.7 million- an attention getting 3000 per cent jump over 1995’s $ 511000.” Clearly, the trend had caught on.

Boo.com

Similarly, Boo.com was an online fashion company that was founded in 1998 by Ernst Malstom, Swedish poetry critic, and Kajsa Leander, former Vogue model. Aspiring to be the “premier online location where the cool and the chic would be able to buy their clothes,” Boo.com launched with 400 employees in eight offices.

However, in as much as only 20% of UK households had access to the internet, the company had few visitors to its sites and not enough sales to sustain itself. Furthermore, the website’s features could not be fully accessed with the dial up connection in UK households. As a result, the company had to close down two years later.

Question is: Could Boo.com have done anything differently?

To start with, Boo.com impacted its market in very much the same way that Amazon.com impacted theirs. Indeed, the company capitalised on a growing trend in the use of the internet, to change the way that an existing job was being done, i.e purchase of fashion.

The uncertainties that Boo.com faced were quite similar to those faced by Amazon.com. Yet, unlike Amazon.com, the company did not understand its market impact and as a result, it did not try to overcome the uncertainties associated with the idea.

For instance, it should first have had market intelligence pertaining to the rate of growth in internet usage in its different markets. Market intelligence would have revealed that only 20% of UK households had access to the internet, and that information would have enabled the founders to adequately gauge the scale of their initial business and potential rate of adoption.

Then, with a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), Boo.com would have identified the barriers to adoption. For instance, it would have discovered sooner that the features on its website were not supported by dial-up connection and it could have perhaps simplified its website or found ways to get around the problem. The MVP would have also allowed the company to test the fit between the service and markets and the fit between the business model and markets.

Instead, the company was focused on scaling and as a result it did not survive.

Thus, by understanding the market impacts of innovations and by understanding their implications for the development, commercialisation and scaling of new ideas, innovators can avoid diving into new ventures armed with only their gut feeling, and can successfully bring their ideas to markets.

Melina Padayachy is an affiliate alumnus of the Birkbeck Centre for Innovation Management Research. This blog is adapted from an excerpt of her new book, The Innovator’s Method: Bringing New Ideas to Markets.

Based on an analysis of past innovations and of start-ups that have failed, The Innovator’s Method identifies a unique link between how an idea would impact the “job to be done” of its market and its ensuing development, go-to-market and scaling strategies.

Further Information: