This post was contributed by Dr Eckard Michels, from the Department of European Cultures and Languages.

The Guillaume affair is one of the most well-known political scandals and Günter Guillaume is certainly the most famous spy in German history. His arrest as an East German Stasi agent in April 1974, after having worked for more than 18 months as a close aide to the first Social Democratic Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt, resulted in the resignation of the latter two weeks later. Guillaume and his wife Christel, who was also a Stasi agent, had moved from East Berlin to West Germany in 1956 with a Stasi brief to infiltrate the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Guillaume made a career as a party functionary in Frankfurt. With Social Democratic take-over in 1969 in Bonn, Guillaume joined the ranks of the Bundeskanzleramt as a desk officer, initially responsible for contact with the trade unions. In 1972, he received a further promotion to become one of Willy Brandt’s three personal assistants.

The Guillaume affair is one of the most well-known political scandals and Günter Guillaume is certainly the most famous spy in German history. His arrest as an East German Stasi agent in April 1974, after having worked for more than 18 months as a close aide to the first Social Democratic Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt, resulted in the resignation of the latter two weeks later. Guillaume and his wife Christel, who was also a Stasi agent, had moved from East Berlin to West Germany in 1956 with a Stasi brief to infiltrate the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Guillaume made a career as a party functionary in Frankfurt. With Social Democratic take-over in 1969 in Bonn, Guillaume joined the ranks of the Bundeskanzleramt as a desk officer, initially responsible for contact with the trade unions. In 1972, he received a further promotion to become one of Willy Brandt’s three personal assistants.

In 1981, after seven years in West German prisons, the couple returned to the GDR in exchange for West Germans who had been held in GDR custody. After 25 years of absence, the two former spies adapted with difficulty to life in the country for which they had spied.

This astonishing story has already inspired the arts in Germany and Britain, not least with Michael Frayn’s highly successful 2003 theatre play Democracy.

However, historians so far have turned a blind eye to this case, not least due to the lack of available primary sources. But more than 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, enough material from the Stasi files has come up to write this story from the East German perspective, in particular Guillaume’s recruitment by the Stasi and his passing of secret information from West Germany to his spy masters in East Berlin. Additionally, the German Freedom of Information Act of 2006 now empowers historians to request the release of secret files from (West) German government institutions, i.e. material which, due to its secret character, has not yet been handed over to the archives. Thus, I was the first historian to have requested and been granted access to the secret files of the Bundeskanzleramt, the German Cabinet Office, for which Guillaume had worked from 1970 to 1974. This enabled me to thoroughly investigate the West German side of the story, in particular how Guillaume was able to join the ranks of the Bundeskanzleramt even though there had already been doubts about his reliability in 1969/70, his work for Willy Brandt and his access or non-access to sensible information about the West German government.

Because this prominent case has generated so much material, archival sources, autobiographical accounts of the protagonists and very dense contemporary media coverage, it is perfectly suited to explore the personal dimension of Cold War espionage between the two Germanys.

In my forthcoming book, I have investigated patterns of recruitment for the Stasi and the original motivation of the Guillaume couple to work as spies for the Communist GDR. I have also assessed to what extent the environment in the West, changing personal circumstances and pure “Eigensinn” (Alf Luedkte) affected the intelligence performance of Günter and Christel Guillaume in the eyes of the East German spy masters. I question the alleged superiority of the Stasi and other Communist intelligence services in “human intelligence” over its Western adversaries, in particular the West German Bundesnachrichtendienst (Federal Intelligence Service). My biographical study, spanning from the early 1950s to the early 1990s, looks at how individuals experienced espionage and tried to make sense of their intelligence activities, be it as active Stasi spies, convicts in West German prisons, celebrated heroes in the GDR after their release or impoverished Stasi pensioners after German unification in 1990. Thus the book is at the same time an inter-German migration and mentality study at a micro level which reaches beyond the confines of mere intelligence history at “grass roots”.

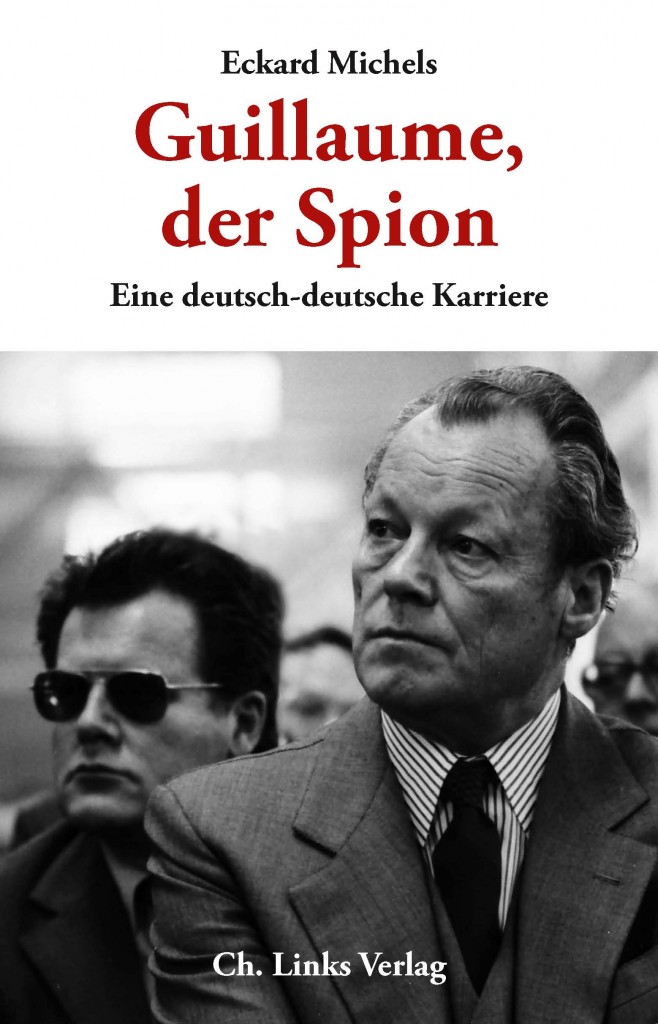

Guillaume, der Spion: Eine deutsch-deutsche Karriere (Guillaume, the spy: A Career between the two Germanys), by Eckard Michels, will be published in February 2013 by the Christoph Links publishing house, Berlin. There will be a book launch on 8 March 2013 from 6pm to 8 pm in the Keynes Library at 43 Gordon Square, London.