Some 34 million people globally are living with HIV. Since 1981, when the first cases of what we came to know as AIDS were diagnosed in the United States, more than 60 million people have been infected and more than 30 million have died from AIDS-related causes. The most recent data indicate that more than two million people a year are newly infected worldwide, the vast majority of these in the resource poor countries of the South, especially those of sub-Saharan Africa. In Western and Central Europe there are some one million people living with HIV, of which approximately 100,000 are in the UK (with a quarter of these unaware of their HIV positive status).

It is a tragic indication of the impact that HIV and AIDS have had on our planet in the past thirty years that these morbidity, mortality and new infection figures represent something of an improvement. The rate of new infections has fallen by almost a fifth since 1999 and appears to be levelling out; one-third of the 15 million people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries have access to treatment. Consequently, the number of deaths is falling, and the number of people living with HIV is stabilising. To this extent the global AIDS response has been a success, and for this we should acknowledge not only the financial resources countries and individuals have made available, but the invaluable contribution of scientists, healthcare workers, academics, civil society organisations, international bodies such as UNAIDS and the World Health Organization and – most importantly of all – people living with, and affected by, HIV. Without the concerted effort and dedication of all these actors and activists the individual, social and economic impact of the virus would be even more catastrophic than it has been.

Central to the success of these efforts has been the recognition that our response to HIV and AIDS must be informed by human rights principles, including the fundamental right to non-discrimination and the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. HIV impacts disproportionately on those who are stigmatised, marginalised or who lack economic or social capital (men who have sex with men, women and girls, sex workers, migrants and displaced people, injecting drug users). Prevention efforts, and access to treatment and care, will only be successful if those most at risk of infection, or already living with HIV, are given – and experience – the respect and support to which they are entitled as of right, without judgement.

Central to the success of these efforts has been the recognition that our response to HIV and AIDS must be informed by human rights principles, including the fundamental right to non-discrimination and the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. HIV impacts disproportionately on those who are stigmatised, marginalised or who lack economic or social capital (men who have sex with men, women and girls, sex workers, migrants and displaced people, injecting drug users). Prevention efforts, and access to treatment and care, will only be successful if those most at risk of infection, or already living with HIV, are given – and experience – the respect and support to which they are entitled as of right, without judgement.

Despite this, governments across the world persist in introducing, implementing and enforcing punitive and coercive laws which reinforce stigma and popular misconceptions. One of the most egregious examples of this in recent years was the introduction by Greece’s Minister of Health of a law which resulted in the detention and forcible HIV testing of hundreds of women in Athens alleged to have been sex workers. Those who tested HIV positive were charged with a range of serious offences (most of which were subsequently dropped or reduced), detained in inhumane conditions and had their photographs published in the national media. The law that permitted this was unnecessary, disproportionate. and resulted in a gross violation of the right to respect for private life. Introduced immediately before the hotly contested and contentious Greek elections of May 2012, many commentators suggested that the measure was a cynical gesture that played to populist sentiment in times of austerity. It was condemned by national groups and activists, and by international organisations and health experts and was repealed in May 2013. In July, however, it was reinstated – with the support of the Greek Centre for Disease Control, and to the dismay of those who thought reason had triumphed over prejudice. The President of the International AIDS Society, Françoise Barré-Sinoussi (a co-discoverer of HIV), speaking at the Society’s conference in Kuala Lumpur this summer expressed her clear disappointment:

“As President of the IAS I strongly condemn this move and urge the Greek Government to rethink its position. HIV infections are already increasing in Greece due to the economic crisis and a mandatory policy of detainment and testing will only fuel the epidemic there.”

As yet, however, there seems to be no rethinking, and new infections in Greece increase at a rate significantly higher than elsewhere in the EU.

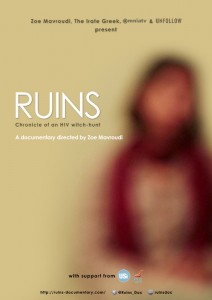

Ruins, a documentary by Zoe Mavroudi about the Greek law and its impact on the women who were rounded up in 2012, had its UK première at Birkbeck on Friday 18th October, supported by the Birkbeck Gender & Sexuality (BiGS). In it, Mavroudi shows the way in which economic austerity, fear and ignorance combined to produce a toxic cocktail which not only blighted the lives of individuals but has done serious harm to HIV prevention work in her country. It is an important and timely reminder of the work that still needs to be done in combating HIV-related prejudice, and of the profoundly negative impact that punitive laws can have in the field of public health.

Ruins, a documentary by Zoe Mavroudi about the Greek law and its impact on the women who were rounded up in 2012, had its UK première at Birkbeck on Friday 18th October, supported by the Birkbeck Gender & Sexuality (BiGS). In it, Mavroudi shows the way in which economic austerity, fear and ignorance combined to produce a toxic cocktail which not only blighted the lives of individuals but has done serious harm to HIV prevention work in her country. It is an important and timely reminder of the work that still needs to be done in combating HIV-related prejudice, and of the profoundly negative impact that punitive laws can have in the field of public health.

Matthew Weait is Professor of Law and Policy at Birkbeck and Pro-Vice-Master (Academic Partnerships). He has been a consultant to UNAIDS and the WHO and was a member of the Technical Advisory Group of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law (UNDP). He co-founded the River House Law Clinic, which provides free legal advice to people living with HIV, and which is supported by student volunteers from the School of Law. An article on this theme, “Unsafe law: Health, rights and the legal response to HIV”, based on his inaugural lecture, will be published in the International Journal of Law in Context in December 2013.

Some years ago, I read an article in Brighton Argus about a gay man being prosecuted for infecting his partner with HIV infection. The case was based on the defendant and his partner sharing the same species of HIV virus. I wrote to the DPP to tell them they hadn’t got a leg to stand on because they had not proved which one infected the other. They may both have been infected by common partner. And who in his right mind would have unprotected sex with a man whose sexual history he did not know? I was told rather shirtily that my comments were noted. Later on after having provoked a lot of opposition from health staff dealing with HIV positive patients, the DPP opened their policy on prosecutions for passing on STIs and HIV to public consultation, so I replied along the same lines. What really stopped them was the case of a man being thus prosecuted where he and the men he was alleged to have infected shared what the Police claimed was a virus unique to them: The defense barrister brought a leading HIV virologist as a witness: this virologist told the Court that the defendant and the man he was alleged to have infected could not be claimed to have a unique virus without HIV testing the blood of all the people with HIV infection in the local HIV transmission network: it might be found that everyone else in this transmission network had the same species of virus or it might be found they didn’t. Additionally this virologist stated that sharing the same or even unique viral species was not evidence which one had infected the other. So the Judge direct the jury to dismiss the case because it had not been proven. Any country which criminalizes HIV transmission will make similar mistakes and ought to be challenged especially over the discouragement that criminal sanctions make to the public acceptance of HIV testing.

Some years ago, I read an article in Brighton Argus about a gay man being prosecuted for infecting his partner with HIV infection. The case was based on the defendant and his partner sharing the same species of HIV virus. I wrote to the DPP to tell them they hadn’t got a leg to stand on because they had not proved which one infected the other. They may both have been infected by common partner. And who in his right mind would have unprotected sex with a man whose sexual history he did not know? I was told rather shirtily that my comments were noted. Later on after having provoked a lot of opposition from health staff dealing with HIV positive patients, the DPP opened their policy on prosecutions for passing on STIs and HIV to public consultation, so I replied along the same lines. What really stopped them was the case of a man being thus prosecuted where he and the man he was alleged to have infected shared what the Police claimed was a virus unique to them: The defense barrister brought a leading HIV virologist as a witness: this virologist told the Court that the defendant and the man he was alleged to have infected could not be claimed to have a unique virus without HIV testing the blood of all the people with HIV infection in the local HIV transmission network: it might be found that everyone else in this transmission network had the same species of virus or it might be found they didn’t. Additionally this virologist stated that sharing the same or even unique viral species was not evidence which one had infected the other. So the Judge directed the jury to dismiss the case because it had not been proven. Any country which criminalizes HIV transmission will make similar mistakes and ought to be challenged especially over the discouragement that criminal sanctions make to the public acceptance of HIV testing.