This post was contributed by Professor Nick Keep, Executive Dean of the School of Science. Professor Keep attended the Birkbeck Science Week 2016 film screening of “Life Story: The Race for the Double Helix” on Monday April 11 at the Birkbeck Cinema.

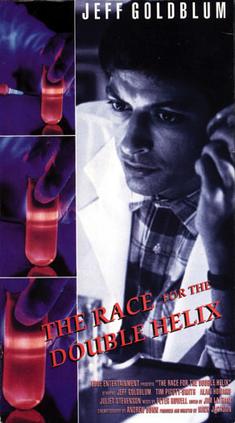

“Life Story: the race for the Double Helix”is a 1987 BAFTA award winning film length TV dramatisation of the story of the discovery of the structure of DNA. The film screening was co-introduced by Dr Richard Hamblyn from the Dept of English and Humanities, who works at the interface of science and literature, and Dr Tracey Barrett from the Dept Biological Sciences, a female protein crystallographer in a Birkbeck tradition that goes back to Rosalind Franklin.

Richard described the film as having two classic odd couples; Crick and Watson in a glossy tourist Cambridge, and Wilkins and Franklin in a rainy London, contrasting with Franklin’s former sunny life in Paris and the easy going relationship with her previous collaborator Vittorio Luzzati, the inventor of the Luzzati plot.

The search for truth in science

Tracey outlined the importance of the science and the changes for women in Science. There are no longer men-only common rooms, such as Franklin encountered at Kings, but there are still problems. They also discussed the interplay between the search for truth in science and competition to be first and famous. Birkbeck is mentioned in the film as the place of refuge Franklin can relocate to escape the oppressive atmosphere at Kings. Richard quoted Rosalind Franklin as writing that she “will be moving from a palace” (Kings) “to a slum” (Birkbeck)” but I’m sure I will find Birkbeck pleasanter all the same”.

The film itself was excellent with Juliet Stevenson as Franklin, Alan Howard as Wilkins, Tim Piggot-Smith as Crick and Jeff Goldblum as the ambitious Watson. I found Clive Panto very convincing (if a little overweight) as Max Perutz, the only character that I knew in person, albeit later in his life. The widespread smoking was an authentic period touch that stood out for me. Whether a 2017 production would do that I am not sure.

Discussing the injustice

After the showing, the audience discussed the injustice of Rosalind Franklin not winning the Nobel Prize. Firstly the prize is never awarded to more than three people so a decision had to be made and by this time Rosalind Franklin had tragically died. Interestingly, checking afterwards, the ban on posthumous prizes was only formalised in 1974, well after the 1962 award for DNA (See section on Posthumous Nobel Prizes), although observed in practice for Science awards until it was discovered that one of the 2011 winners for Physiology and Medicine had died three days before the announcement, but this was not known to the Swedish Academy when they released the names.

The 1961 Peace prize, just a year before the Medicine and Physiology award to Crick, Watson and Wilkins, was knowingly awarded to the UN Secretary General, Dag Hammarskjöld, who had recently died in an air crash, as was the 1931 Literature Prize to a Swedish Poet. Whether Rosalind Franklin is better known now for not having been awarded the Nobel Prize, than she would have been if she had received it is a matter for debate. Birkbeck, where she worked at the end of her life, remembers her via the Rosalind Franklin Laboratory built in 1996 and, from this year, the annual Rosalind Franklin lecture by a leading woman scientist in a field Birkbeck researches in.

Find out more

The search for life in the universe ranging from simple organisms to intelligent beings was the subject for

The search for life in the universe ranging from simple organisms to intelligent beings was the subject for