Mauro Pirarba BSc, a first year Planetary Sciences Graduate Certificate student and Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society discusses Professor Ian Crawford’s talk, given during Science Week, on astrobiology and the search for life in the universe.

How common is life in the universe?

Sadly, we don’t have an answer to this basic question. All we can say is that life arose at least on one planet: the Earth. Fossils in very ancient rocks tell us that there were unicellular organisms around 3.5 – 3.8 billion years ago and it is probable that the first life forms were even older, i.e. life appeared on Earth “easily”, as soon as conditions were not too harsh.

If that is the case, we would expect microbial life to have arisen independently in other places in the solar system where conditions were similar to the early Earth a thick atmosphere that protected the surface from radiation, mitigated temperature variations and allowed the presence of liquid water on the surface.

Although water was once abundant on Mars, things changed dramatically billions of years ago, making the surface of the planet a very inhospitable place for life. Our only chance to find extant or past life on Mars is to look under the surface, something that the current NASA rovers cannot do. This will be within the grasp of ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover, landing on Mars in 2021. Still, the search will only be skin-deep. Future robotic missions, the collection of samples to be returned to the Earth for sophisticated analyses and possibly the start of the human exploration of the red planet will one day give us a definite answer about the possibility that life arose on Mars.

However, the search for life in the solar system does not end at Mars and Professor Crawford’s audience got particularly excited about a moon, Europa. This is heated by tidal forces while orbiting Jupiter, resulting in the formation of an ocean under its thick icy crust. Water, energy and a rich chemistry could provide all the ingredients for life to have arisen on Europa, perhaps in a similar way to what may have happened along mid-ocean ridges on Earth.

We can also extend our search for habitable worlds beyond our solar system. Over the last 20 years thousands of planets orbiting other stars have been discovered. Trying to image these specks of light in the glare of their stars is still a formidable challenge, but large telescopes or sets of instruments flown into space will make it possible. Such instruments will be able to “analyse” the atmosphere of these worlds and look for hints about their potential habitability.

The Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI), offers a different and “targeted” approach to the search for life in the universe, in the sense that it is restricted to technological civilizations interested in communicating with other intelligent beings that have been able to build radio telescopes. The search was started by Frank Drake in the 1960s and has so far not found a single artificial radio signal.

Can we conclude that we are the only intelligent species who built radio telescopes in the galaxy?

No, we can’t, or at least not yet, according to Professor Crawford.

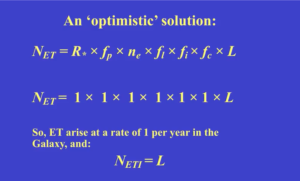

Drake came up with an equation to try and estimate the number of technological civilisations in our galaxy. Most of the terms in the equation were unknown in the 60s, but astronomers have since constrained a number of them. In the most optimistic scenario (giving the highest possible value to each term) and assuming that the average technological civilsiation lasts for 1000 years, at present there should be 1000 of them. The vastness of our galaxy justifies our failure in detecting them so far.

On the other hand, considering that it took over three billion years for life on Earth to “invent” multicellular organisms and out of the many millions of species that inhabited the planet only one has evolved to become a technological civilization, we could conclude that we may be alone in the (observable) present universe.

The reality, as Professor Crawford concluded, could be anywhere between those extremes and our inability to constrain them is a measure of our ignorance.

The closing slide of the presentation could have not been more appropriate:

“The discussions in which we are engaged belong to the very boundary regions of science, to the frontier where knowledge… ends and ignorance begins.” William Whewell (1853)

In spite of all the progress made by our species over the last century and a half, those words still hold true.

Does anyone want to join the search?

Interesting, amusing and very ironic reflections!!!