As the centenary year of women’s suffrage draws to a close, The Centre for the Study of British Politics and Public Life has been examining how and why we celebrate centenaries.

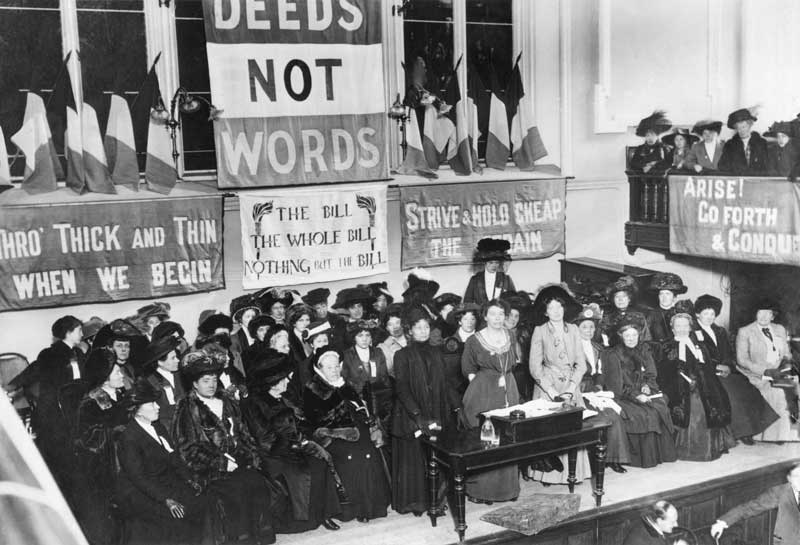

What springs to mind when you hear the words ‘women’s suffrage’? The purple, green and white banners of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), Emily Wilding Davison losing her life in protest at Epsom Derby, or perhaps the lively rendition of ‘Votes for Women’ given by Mrs Banks in Mary Poppins? All this and more was acknowledged at a fascinating event from The Centre for the Study of British Politics and Public Life at Birkbeck on Tuesday 13 November, as the centenary year of women’s suffrage draws to a close.

Chaired by Professor Sarah Childs of Birkbeck’s Department of Politics, Celebrating, Commemorating, Centenaries of Suffrage aimed to address the centenary of women’s suffrage by exploring how and why we celebrate centenaries.

The first part of the evening saw Dr Mari Takayanagi, a Senior Archivist at the Parliamentary Archives, deliver her paper Celebrating Suffrage Centenaries. She began by explaining how one of the most important anniversaries in the UK’s democratic history is in many respects problematic. As the UK celebrates the centenary of the Representation of the People Act 1918, it’s worth remembering that the Pitcairn Islands in the Pacific have already commemorated their 175 anniversary of women’s suffrage, while the more local Isle of Man has had equal suffrage since 1881. Suffrage has rarely been awarded, at least at first, without being linked to age, race, marital status, class and even relation to men in the armed forces, and British women would wait another ten years for the Equal Franchise Act of 1928 to grant them the same voting rights as men.

Still, this first legislative step towards equal suffrage should be recognised and the impact of this year of national commemoration has been both powerful and wide-ranging. Centenaries act as a catalyst for reflection, prompting greater public awareness and accelerating academic research. During this period, government grants were awarded to projects addressing discrimination and improving female work progression and numerous exhibitions were curated to capitalise on the renewed interest in women’s suffrage. Institutions that boasted some of the biggest collections on this subject, such as the Museum of London and the Manchester People’s Museum, used the opportunity to draw public attention to their permanent exhibits.

Dr Takayanagi argued that centenaries hold a unique emotive power, asking whose memory should be drawn on in their commemoration, and whose memory should be honoured? Unsurprisingly, memorable protagonists of the suffrage movement took centre stage in the celebrations. Emily Wilding Davison alone was remembered through documentary, commemorative services, a play, a plaque, a tree, not to mention #Emilymatters and an appearance at the 2012 Olympic opening ceremony. Indeed, the marking of the centenary of suffrage has in many ways been dominated by the militant side of women’s suffrage, the WSPU. The striking purple, white and green banner now seems synonymous with the entire women’s suffrage movement, leaving the red of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the gold of the Women’s Freedom League to jostle for shelter underneath it.

Undoubtedly, said Dr Takayanagi, the WSPU knew a thing or two about marketing, but could the success of their particular brand of militant feminism ring truer with today’s audience and the swelling anger of the #Metoo campaign than their non-violent counterparts? Thirst for feisty feminist heroines can be quenched more easily with an Emmeline Pankhurst than a Millicent Fawcett. Either way, Dr Takayanagi hopes that the huge public interest roused in 2018 will continue as the ten year countdown to the centenary of universal suffrage begins.

This insightful talk was followed by a roundtable discussion with Mary Branson, Parliament Artist in Residence 2016, and Dr Red Chidgey, lecturer in Gender and Media at Kings College London. The thread running through a broad and lively discussion and Q&A session seemed to be the desire for the uncovering of an inclusive, collective memory of the fight for universal suffrage. Branson discussed how her discovery of a staggeringly wide range of arrested female protestors through the parliamentary archives led her to create an art installation, New Dawn, that would celebrate the ordinary women of the suffrage movement. Dr Chidgey drew on the example of modern feminist movements, such as Sisters Uncut, who sport the colours of the WSPU, to ask if the ‘beloved national feminist memory’ of women’s suffrage could become a tool of protest, rather than its result.

The evening was aptly concluded by Sian Norris, Ben Pimlott Writer in Residence 2018 in the Department of Politics, who read two monologues from the pamphlet And in the end, we won: Three stories of women’s protest, written as part of her residency at Birkbeck. As her words led us from the mind of a silenced woman of pre-1918 Britain to one who feels she has no voice in the era of the Trump administration, we appeared to need the memory of the suffrage movement more than ever before.

Further information: