This article was written by Jack Watling, a Hobsbawm scholar studying for his PhD at Birkbeck

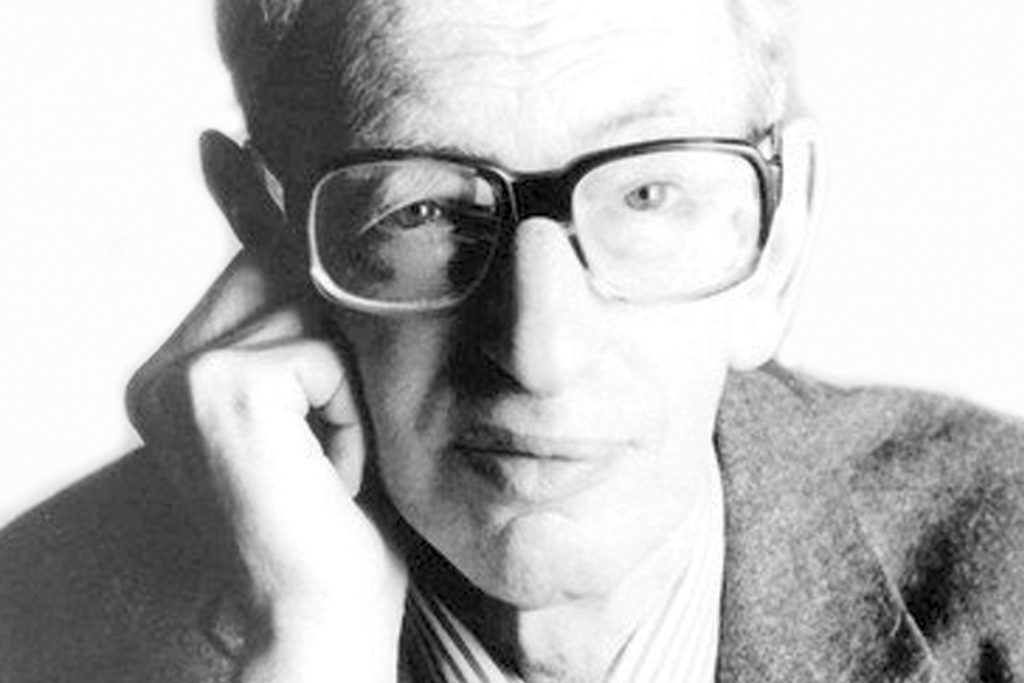

Professor Eric Hobsbawm

What is the duty of the historian to society? That was the question taken up by Catherine Merridale in her Eric Hobsbawm Memorial Lecture, held at Senate House, on Monday 22 May.

In answer Merridale reached into her own past, as a pioneering oral historian of the Soviet Union, its collapse, and the emergence of the new Russia. “This evening,” she said, “I appear before you in the guise of a witness.”

Merridale arrived in Russia in 1982, and entered an exciting and vibrant world in which she was unmistakably an outsider. Amidst the archives and late night arguments over art, literature, and politics, Merridale described the USSR as “red and brown.” Red pervaded public space, the ever-present colour of communist ideology; “brown was the stuff that leaked out when the snow thawed.”

Eventually the brown, oozing through the cracks of failing industries, the rot in the Moscow food warehouses, the bodies bearing testament to past atrocities, would see the whole edifice crumble, and fall away. In the heady days of the 1990s liberation was not conducive to reflection. “Everyone went shopping.” Merridale recalled a friend demanding to know “Ideology! What good is that? We are sick of it. We want a society like yours without an ideology.”

The idea that British society lacked ideology was not just wrong, but dangerous, Merridale argued, the assuredness of western economists who flooded into Russia in the 1990s was misplaced. They believed they had an answer to a country whose problems they barely attempted to understand. “Their intervention was a disaster.” What were they but ideological, working from assumptions? To be blind to one’s biases is invariably to fall victim to them.

It was a highly suitable subject for a lecture commemorating the late Eric Hobsbawm, described by Birkbeck’s Professor Joanna Bourke as one of “the most exciting and influential historians of the Twentieth Century.” Hobsbawm’s magisterial historical quartet, running from the French Revolution to the Cold War, set a benchmark for the integration of cultural, economic, and political history. Yet Hobsbawm’s work was also an internal struggle between ideology and intellectual rigor. Hobsbawm was a dedicated Communist, and remained so long after it was fashionable. He was a true believer.

There can be no doubt that his political outlook shaped his work, and in a few cases confounded Hobsbawm’s commitment to the historical method. But Hobsbawm was both aware, and consciously challenged himself to confront his own assumptions. I saw this personally as an undergraduate when I was given his copy of Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, a book banned in the Soviet Union, in which the renowned Soviet journalist contended that there was really very little to distinguish Communism from Fascism.

Merridale contends that today society is “drowning in the twittering present,” our communications rarely archived, our historical memory diminishing. We live in a society “that does not force us to confront ideas we find uncomfortable.” The historian then, who always stands as an outsider, peering into the past, ought similarly to force society to confront its own assumptions; to be aware of its ideological tendencies, and to struggle with them. History ought to make society self-conscious.

It was a compelling mission statement, which Merridale entrusted to the new generation of historians that the Hobsbawm Memorial Lecture aims to inspire. Associated with the lecture is the Hobsbawm Memorial Fund, which provides scholarships to support both Masters and PhD students.

Speaking for myself, such funds are transformative. When I finished my degree I was not in a financial position to fund a Master’s, and yet an MA was a prerequisite for a PhD. There is little government support for Master’s students. The Hobsbawm scholarship was therefore pivotal in my entering the academy. I am now two years into my PhD.

And I am not alone. “Honestly, it’s the only way,” said Sean, an aspiring early modernist who attended the lecture, and is hoping to apply to the Hobsbawm Memorial Fund to support a Master’s.

With Brexit on the horizon it is vital that Britain remains historically conscious. Russia, Merridale explained, has resurrected the Romanov’s, retreating into costume dramas to avoid confronting the contradictions that remain unresolved in Russia’s past. “They failed their own society at its crucial turning point.”

But far from suggesting a complacent superiority Merridale noted that “we Russians and Brits were trapped under the landslide of our victories” in the wake of the Second World War, and here in Britain there is also the tendency to seek comfort in a romantic fantasy of Kings and Queens, that never challenge us to ask who we are, or who we ought to be.

“It is the job of the outsider to be shocked,” Merridale said, as they explore, and like Socrates’ horsefly, to shock others.