Mark Blacklock on What I Think I Believe

Mark Blacklock on J.G. Ballard’s ‘What I Believe’ (1984)

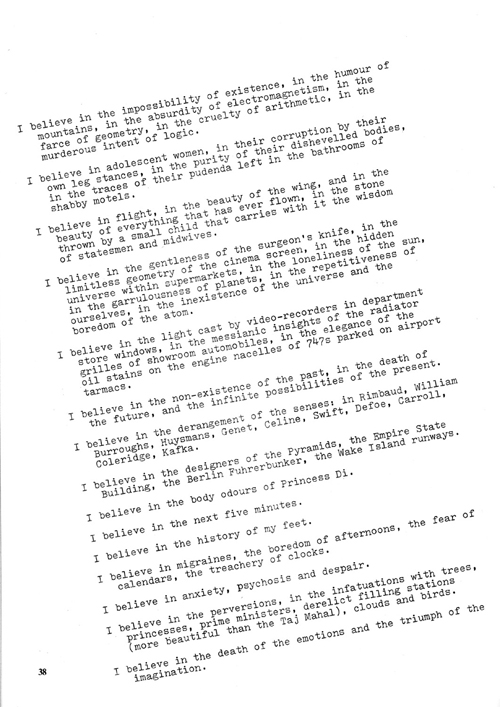

Researching the non-fiction of J.G. Ballard I return again and again to ‘What I Believe’, first published in the inaugural issue of the French Magazine Science Fiction in 1984, a response to the editor Daniel Riche’s invitation to describe “Ce que je crois.” Republished later that year in Interzone, it was given the personal touch of being presented in typescript with title and byline in Ballard’s handwriting.

Simon Sellars, the editor of the website Ballardian and co-editor of Extreme Metaphors, a vivid and stimulating collection of Ballard’s interviews published in 2012, offers a useful precis of the themes of the piece:

There, we find an index of his obsessions, including the ‘power of the imagination’; motorways; birds (indeed, flight of all kinds, powered and unpowered); the ‘confidences of madmen’; ‘the beauty of the car crash’; abandoned hotels; forgotten runways; Pacific Islands; ‘all women’; supermarkets; the ‘genital organs of great men and women’; the death of the space age; Ernst, Delvaux, Dali and Chirico; and all the invisible artists within the psychiatric institutions of the planet’.

‘In fact’ comments Sellars, ‘that small list could be a mini-index to this present volume, in which all its elements are present and correct, and which in turn function as launchpads for other explorations, other themes: psychological, ontological, metaphysical, sociological, political, satirical, comical.’ (xix)

‘What I Believe’ certainly does act as both index and launchpad. It is also, by definition, a credo, close in tone to prayer and reliant on the same incantatory repetitions. This is Ballard playing up to the role of prophet in which he has been cast, the “seer of Shepperton” of literary legend. He’s delivering it straight but only the unwary will read it that way. If Ballard is assuming the role of preacher, we should suspect him of knowingly borrowing the robes. His work is persistently interested in figures who frame themselves as messianic but they’re mostly cousins of Colonel Kurtz.

In the broader context of that work, ‘What I Believe’ extends an engagement in the detournement of mass media modes and formal experiments that was a continuous strain from Ballard’s 1950s billboard-piece Project for an Unfinished Novel, through a series of ‘advertiser’s announcements’ published in Ambit in the 1960s and onto 1985’s ‘Answers to a Questionnaire’, which frames the autobiographical answers without providing the questions, inviting the reader to complete the other half of the questionnaire in her imagination. When Ballard responded to Riche’s stock question for a repeat column with something as rich as ‘What I Believe’, he was taking the opportunity to experiment with a format rarely questioned by magazine readers.

J.G. Ballard, ‘What I Believe’ (1984)

Dig deeper and I think we uncover another layer of formal influence. ‘What I Believe’ surely owes a significant debt to the manifesto form, a favoured form not just of Ballard’s beloved Surrealists but of avant-gardes of all hues. Mary Ann Caws, editor of Manifesto: a Century of Isms, offers an analysis of the poetics of this strident but ambivalent mode. Caws writes:

The manifesto was from the beginning, and has remained, a deliberate manipulation of the public view. Setting out the terms of the faith toward which the listening public is to be swayed, it is a document of an ideology.

J.G. Ballard, ‘What I Believe’ (1984)

Clearly, ‘What I Believe’ is a setting out of a faith. It is certainly a manipulative document – a form of advert for a particular imaginary? – but if it has any ideology it is aesthetic rather than political, psychological rather than social.

In times in which so many seem so certain in their beliefs, I find my own troublingly unstable and abstract: I don’t have sufficient purchase on the “identity” that seems to be required. I think I believe that all experience is available for cultural re-use. In that spirit, and in oblique tribute to Ballard’s faith, I borrow the below beliefs from the firebrands in Caws’s anthology.

What I Believe: a Compound Credo

I believe that this action will originate in the mind of the beholder and will arouse in his imagination any number of fantasies whose meaning will be broad or limited according to his sensitivity and imaginative aptitude to enlarge or diminish.

I believe that this is the origin of my true inventions.[1]

I believe I still have the force to return among men.[2]

I believe that here in America, some of us, free from the weight of European culture, are finding the answer, by completely denying that art has any concern with the problem of beauty and where to find it.[3]

I believe that lyricism, born in the subconscious, purified into a clear or confused thought, creates phrases which are entire verses, without the necessity of counting so many syllables with predetermined accentuation.[4]

I believe that plastic beauty in general is totally independent of sentimental, descriptive, or imitative values.[5]

I believe in the theoretical aspects of painting because I believe it produces better painting, and I think I can say I have been a fair exponent of the imaginative idea.[6]

I believe in

you my soul, the other I am must not abase itself to you, And you must not be

abased to the other.[7]

[1] ODILON REDON, ‘Suggestive Art’ (1922)

[2] BLAISE CENDRARS, ‘On Projection Powder’ (1917)

[3] BARNETT NEWMAN, ‘The Sublime Is Now’ (1948)

[4] MARIO DE ANDRADE, ‘Extremely Interesting Preface’ (1922)

[5] FERNAND LEGER, ‘The Aesthetic of the Machine’ (1924)

[6] MARSDEN HARTLEY, ‘Art and the Personal Life’ (1928)

[7] WALT WHITMAN, ‘Song of Myself’ (1855)