by Billy Stanton

On Friday 15th June the ‘Tragedy and Sexuality’ series at Birkbeck cinema, organised by James Brown and on this occasion introduced by Carmen Mangion, concluded its current program of screenings with the classic Black Narcissus, one of the jewels in the crown not just of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger but of the wider British cinema.

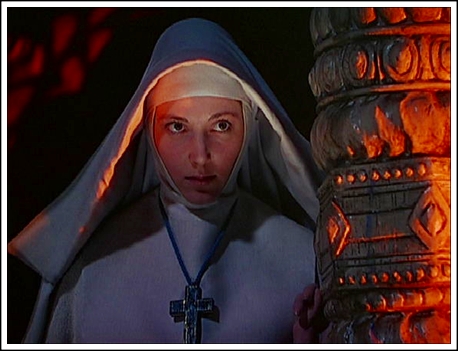

The film itself glows on the big screen, even without the benefit of a 35mm print; Jack Cardiff’s cinematography, his exquisite balancing of bright and misty blues and overheated, fire-and-brimstone reds, is a marvel of design, deliberation and deep understanding of the ways colour can signal, underline and mutate the emotional or psychological content of any scene and any narrative. Seen today Black Narcissus seems like an unlikely predecessor and partner to the early work of Australian film-maker Peter Weir, particularly his two masterpieces Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave, which placed in simultaneously stark and mystical comparison the mores of the Western colonialists and settlers and the ancient meanings of the aborigine landscape and culture (meanings often ignored, attacked or unintelligible to the Westerner). In particular there is much to be said for the way the echoes of encroaching madness arising out of the repression of the nuns of Black Narcissus resonate through the disappearance of the schoolgirls in Weir’s …Hanging Rock and the subsequent adriftness and vitriol felt by those left behind (and there is a lot of Cardiff visible in that scene in which the now rejected and red-dressed schoolgirl is set upon by her monochromatic classmates in Weir’s film).

What this seems to suggest is a development in Powell’s treatment of the landscape and the people and outsiders who come to occupy it. As discussed in the post-film Q and A session, A Canterbury Tale presented a view of Anglo-American communality fostered by romantic obsession with, and hypnotism caused by, the age-old cries and whispers of the English countryside, a film which ends with a beautiful restoration-of-the-spirit in the deeply Christian space of Canterbury Cathedral (and it’s arguable as to whether a cathedral has ever been better filmed in cinematic history, let alone the British countryside). Meanwhile, the following year’s I Know Where I’m Going!, similarly dwelling in myth and neo-romanticism, presented an outsider first testing herself against the traditions and dangerous realities of life in the remote outer reaches of Scotland, and then submitting to its charms, the film’s idealised version of a life perched between the experience and understanding of peril and great warmth and rootedness. Black Narcissus, in contrast and in keeping with the previously-mentioned Weir films, presents outsiders unable to cope with the landscape and history of the colonised India, and finding no such ability to come to terms with any of it: instead the nuns are driven out of their faith, into violent and erotic obsession, into tragedy and eventually out of their new-found ‘home’ and back to the security they once knew. As such, Black Narcissus is a more sophisticated and more troubling film than most of those that could be seen as constituting a ‘colonial cinema’, for all the dated aspects of cross-racial casting and the (disproven) condescension of some of the white characters.

Following the screening, the panel discussed the use of landscape in Powell and Pressburger’s work, the differences between the film and the original Ruth Gooden novel from which it was adapted (and taken somewhat out of realism and in to something approaching a mystical and elemental abstraction), the realities of life for nuns in remote and more ‘comfortable’ covenants, and the stereotypical and anti-stereotypical presentations of nunhood on-screen (particularly in relation to such themes as the dedication to Christ being driven by earlier failed relationships and the awakenings and stirrings of repressed sexuality, both seen in Black Narcissus).