This article was contributed by Eric Kaufmann, Professor of Politics at Birkbeck’s Department of Politics.

This article was contributed by Eric Kaufmann, Professor of Politics at Birkbeck’s Department of Politics.

National attention focused on the Clacton and Heywood and Middleton byelections because UKIP support rose substantially in both contests over its level in 2010. The media and some commentators have spun the story as a tale of dispossessed voters from forgotten constituencies striking a blow against the political elite. On this view, both the main parties will suffer at the hands of the Faragists.

Yet the data does not support the contention that the economically and politically disadvantaged of all political stripes are in revolt. Instead, the by-elections, and the rise of UKIP more broadly, reflects cultural anxieties and status resentments which loom largest among middle income people who lack degrees. UKIP damages the Conservatives more than other parties and is set to tilt the electoral terrain in Labour’s favour in 2015 and beyond. This means we need to entertain the possibility the Tories may enter the political wilderness, much as the Canadian Tories did between 1993 and 2006 when the populist Reform Party split the right-wing vote.

In Clacton, Douglas Carswell, a high-profile defector from the Tories, carried the seat easily, winning 60% of the vote in a constituency UKIP did not contest in 2010. Popular in Clacton, Carswell carried wide support across a range of social and voter groups. In Heywood and Middleton, UKIP candidate John Bickley won 39%, increasing UKIP’s share by a whopping 36 points over 2010. It was an impressive UKIP tally, but the seat was held by Labour, winning 41% of the poll. Here we have two strong UKIP performances, resulting in a Tory loss in one instance, and a Labour win, albeit narrow, in the other. The constituencies are not typical of the country, but the results are indicative of what may happen in 2015. Why?

First, consider that in both by-elections, Ashcroft polls show the Tories lost a larger share of their vote to UKIP than Labour. These results are corroborated in the admittedly small sample of some 70 British Election Study (BES) internet panel respondents from these seats interviewed in early and mid-2014 about their 2015 voting intentions.

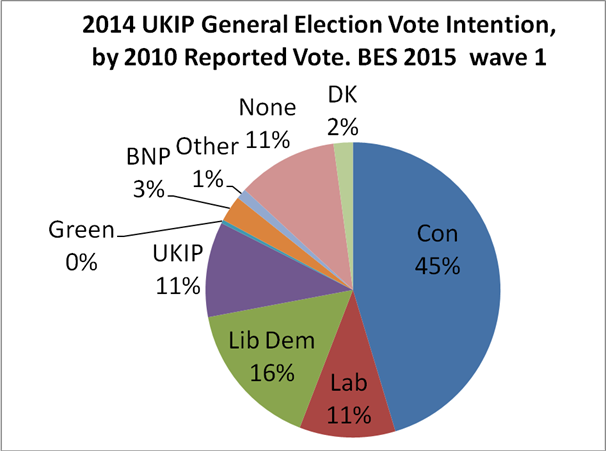

The British Election Study provides data on over 34,000 people, interviewed in both early and mid 2014. Looking at the second wave reveals a stunning pattern: 47 percent of those who voted UKIP in the 2014 European elections said they voted Tory in 2010 compared to just 13 percent from Labour. When it comes to intended vote in the General Election, it’s much the same story: 44 percent of those intending to support UKIP are ex-Tories while just 10 percent said they voted in Labour in 2010.

In terms of current party identification, while 38 percent of those intending to vote UKIP in 2015 identify their party as UKIP, 24 percent say they identify as Conservative, compared to just 10 percent of UKIP vote intenders who currently identify with the Labour party. These data rely on respondents reported retrospective vote. However, the Understanding Society longitudinal survey just compares what people said in the previous wave with what they say in the current wave. These actual results, between 2009 and 2012, confirm the self-reported results from the BES: between 2 and 5 times as many people switched allegiance from Conservative to UKIP as moved from Labour to UKIP.

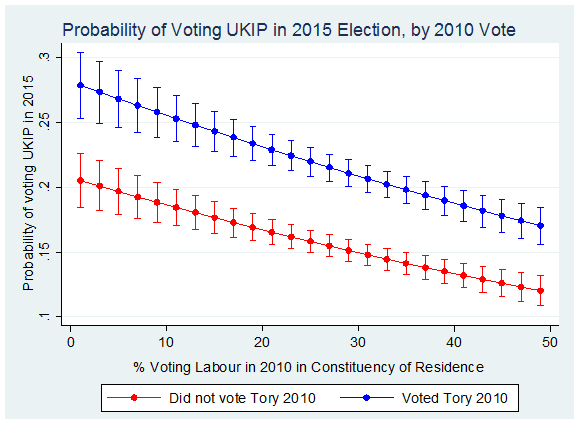

Some suggest Tory defections are in safe Conservative constituencies where they are unlikely to affect the Cameron-Miliband contest. Unfortunately for the Prime Minister, there is no evidence for this. The figure below shows the predicted probability that an individual in the BES will vote UKIP in 2015, on the vertical axis, against the Labour share of the vote in his or her constituency in 2010, on the horizontal. The blue line represents those who voted Tory in 2010, the red line those who voted for parties other than the Conservatives in 2010. This is a multivariate model where we also control for a host of other predictors of UKIP voting, such as age, education, ethnicity and so forth. The cross-hatch lines represent confidence intervals, which are longer at the extremes of Labour share because sample sizes are smaller there.

Two things jump out of this chart. First, UKIP will hit the Tories harder than other parties by 6-8 points across all types of constituency. There is no reluctance among 2010 Tory voters to desert the party for UKIP in marginal seats. Nor are UKIP defectors concentrated among Tory voters in Labour strongholds. Where votes averaged 30% Labour in 2010, often indicating a tight contest, a 2010 Conservative voter has a 21 percent chance of voting UKIP, which falls to just 15 percent among their Labour counterparts. UKIP support is holding steady in the polls, and if this continues, UKIP will pose a threat to Cameron.

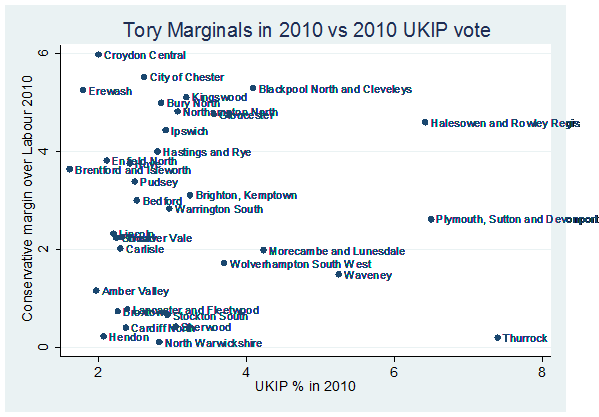

Instead of fixating on the Clactons and Heywoods where UKIP is strong, pundits should focus on marginals where even a small shift to UKIP could tilt things Miliband’s way. We could see upsets not only in UKIP strongholds like Thurrock, but in middle class spots such as Cambridge or Hendon, often in the South of England, where Miliband may pull off an upset. The plot below shows seats the Tories won in 2010 with less than a six percent margin over Labour. These, and more, may be vulnerable.

If UKIP hands victory to Labour, this raises a whole series of important questions. Can the Conservatives strike a deal with UKIP, as with the ‘unite the right’ initiative between the populist Reform party and more elite Progressive Conservatives in Canada? Should Labour rejoice, or should they look to the reinvigorated Canadian Conservatives as a warning that the rise of the populist right can shift a nation’s political culture against them in the long run? Matthew Goodwin and Rob Ford’s excellent book on UKIP warns that the party, with its working-class support base, threatens Labour as well as the Tories. My work suggests working-class Tories rather than Labour traditionalists are most likely to defect to UKIP, but their overall point holds: this is not a movement Labour can afford to ignore.