Dr Isabel Turnadge,née Soar was a Birkbeck alumni who championed women’s right to vote and work after marriage in the 1920s. As part of the College’s 200th-anniversary celebrations Ciarán O’Donohue, PhD candidate in the Department of History, Classics and Archaeology recalls the origins and trajectory of Dr Turnadge’s activism.

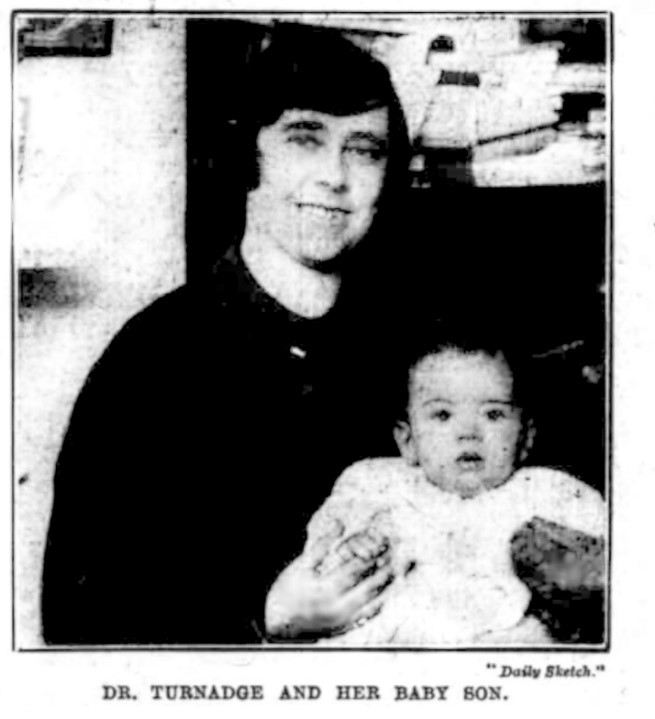

Dr. Isabel Turnadge, née Soar, with her son, Peter James. Becoming a parent will be a turning point for anyone, but perhaps for none more so than Isabel.

Only five PhDs in the sciences were awarded by the University of London in 1921. These were the first people ever to hold the distinction. Among them was botanist Isabel Soar, who had toiled tirelessly every weekday evening after work for five years at Birkbeck College.

Soar was in many ways the archetypal Birkbeckian, engaged as she was in full-time work and part-time study. The daughter of a stationer and a book-seller, Soar was a bright child: a ‘keen student of science, and particularly fond of botany’. After her own schooling, she pursued a career in teaching, taking up her first post as a science teacher in Ipswich in 1907.

Within six short years, she found herself in the daunting position of lecturing to trainee teachers in London at Stockwell Training College: an impressive achievement for one so young. Yet, Soar was not satisfied. Perhaps inspired by the experience of teaching others, Soar was determined to deepen her own knowledge. So, working full-time in the week, Soar began evening classes in botany at Birkbeck.

All her work was crammed into long weekdays. She made ‘it a point never to study on Saturdays, Sundays or other holidays’ and was a fervent believer that there was ‘a time for work and a time for play.’ In 1916, after three years of intense study, dedication and sacrifice, Soar achieved her Bachelor of Science in Botany, with first-class honours. The Middlesex County Times highlighted Soar as ‘an outstanding example of the rewards which await industry and determination.’

Still, Soar’s thirst for knowledge remained unquenched. Immediately after the completion of her bachelor’s she began to pursue original botanical research. Her trademark abundance of determination and its seemingly inexhaustible wellspring ensured she persevered for five long years. In June 1921, Soar’s Ph.D. thesis was approved, and she became the second Birkbeck student to achieve the title of Doctor. Bearing the title, The Structure and Function of the Endodermis in the Leaves of the Abietineae, it was of substantial interest to contemporary botanists. Before the end of 1922, an abridgement was published in The New Phytologist and she was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society.

Meanwhile, her professional life was also reaching new heights. In this same year, she was appointed headmistress of Twickenham County School for Girls by Middlesex County Council. For her work, she was to be awarded an extremely generous commencing salary of £600 per annum. And her run of good fortune was not over yet.

On Saturday 4 August 1923, Soar married Charles James Turnadge. Turnadge was a member of the Aristotelian Society, and was sometime editor of South Place Magazine, the organ of the South Place Ethical Society. Soar took her husband’s name, and they soon departed on their ‘ostentatious’ honeymoon: a six-week motor tour of Devon, Cornwall, Somerset, and Wales.

Life seemed to be going well for Isabel Soar: academically, professionally, and personally. Unfortunately, it was not to last. In November 1926, in what should have been a happy time in her life, Soar, now Dr. Turnadge, was in the newspapers again.

In May 1926, she gave birth to Peter James Turnadge. As a result, she was fired. The Twickenham Higher Education Committee beseeched the Middlesex Education Committee to terminate her employment. They argued that ‘the responsibilities of motherhood are incompatible with her school duties.’

The Chair, and Twickenham’s Mayor, Dr. J. Leeson, defended his actions to the press: ‘with characteristic male impertinence,’ according to the feminist weekly Vote. He asserted that he had warned her, spluttering that it ‘was against my advice that Dr. Turnadge, holding the position she did, ever married… We pay her a good salary, and we want her undivided interests.’

Turnadge’s argument that her being a mother would be an asset to her work was given short shrift. In an interview with the Middlesex County Times, she explained that she was ‘even bold enough to hold the view that, as a mother, I might be better qualified to teach. May not maternal sympathy… be something of a help in training the young?’ She even later argued that ‘single women are not normal, they are emotionally starved.’ Accordingly, large numbers of single women teachers posed ‘a grave menace to the pupils.’ She made the further point that it was ‘absurd to pretend that it would be impossible for me to make adequate arrangements for Peter’ during the day, given her salary. This, similarly, did nothing to move the Committee from its position either.

Her arguments fell on deaf ears. Charles’s birth was the pretence they had been searching for since the wedding. Middlesex Education Committee had a policy that the marriage of an elementary school teacher would void their contract and terminate their employment. At the time of Soar’s wedding, however, this did not cover the marriage of secondary school teachers. The loophole was promptly closed afterwards, and although they could not act retrospectively, Soar became an exception in a fragile position, with a hostile employer.

Turnadge’s case added fuel to a debate which was already raging about the state’s employment of married women. Clearly, not everyone was in favour. Upon hearing of Turnadge’s dismissal, author James Money Kyrle Lupton sent his opinions into the West London Observer. ‘This position ought to be held in all cases by a single woman, who can devote all their time to the position,’ Lupton opined, continuing that besides a ‘married woman with any family cannot do her duty to the school and her home at the same time – this is self-evident.’

Others were appalled by the decision. Bernard Shaw quipped that ‘Twickenham is not very far from the river, and the sooner the people of Twickenham put their Higher Education Committee in the river, the better.’ Vote declared the incident ‘sufficient indication of the necessity for further vindication of the important principle of the freedom of the married woman.’

As for Dr. Turnadge herself, the bar imposed on married women teachers became the next target of her fiery determination and indefatigable work ethic. On 7 February 1927, Turnadge delivered a lecture entitled “Marriage or Career?” to the Six Point Group, a feminist organisation founded by Lady Rhondda in 1921. In Turnadge’s lecture, she decried the ‘present position of women’ as ‘most unsatisfactory, because we are not chattels, yet we are not regarded as responsible individuals who should be allowed to choose our own paths in life.’ For her, this was an issue of state interference in private life, and along undeniably unequal lines. Some women wanted ‘to continue their work after marriage, and I do not see why anyone should interfere with them,’ she asserted. It was not the work of education authorities to regulate household economies. If they were economically minded, she stressed, they would realise the folly of expending public money on teaching scholarships, only then to dismiss married women outright.

By March, she was honoured at Vote’s annual spring sale, by giving the opening address whilst rubbing shoulders with veteran campaigners such as the president, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. Her focus had crystallised on equal suffrage, for both married and single women.

Her points were direct, brimming with a scientist’s rationality. A woman and her life must no more be interfered with than a man. Anything less than equality would rob the nation of talent. Women should be given the same rights of individual determination. Her conviction was that possessing the vote at 21 was of the highest importance. This is when women were entering their professions, she determined, and so most needed the power to influence policy. Evidently, her experiences had left their mark on her, and she was determined no other woman should suffer the same fate.

When the Equal Franchise Act was passed a few months later in July 1928, the achievement of policy change through the exercise of the vote was in sight. For many women, their objectives had been achieved, their battles over. Lady Rhondda, a suffragette and life-long feminist, recalled some years later ‘that when, in 1928, the vote came on equal terms, one felt free to drop the business.’ For her at least, it ‘was a blessed relief to feel that one had not got to trouble with things of that sort anymore.’

As indomitable as ever, Turnadge’s years of campaigning were only just beginning. As the international organiser for the Six Point Group, we last catch a glimpse of her busy organising a conference in Geneva to lobby for an Equal Rights Treaty. With the confidence equality was well on the way in Britain, her sights were set on the League of Nations.

Today, Birkbeck awards over 100 PhDs a year; quite the difference to a century ago. Yet, it seems that Birkbeck’s students retain the same qualities. Isabel worked consistently, with perseverance and dedication, to follow her passion. She took her fate into her own hands, sacrificing her evenings to better her prospects. And although she faced it in spades, adversity never triumphed over her. She cannot help but remind us of our peers and colleagues in these current days of difficulty, and thankfully Isabel’s virtues seem set to live on in Birkbeckians for another hundred years.

Wonderful and inspiring to read (I am a former graduate of Birkbeck).

Amazing woman. Affects us all. Both my mother and mother-in-law had to cease their teaching careers upon marriage.