This post was contributed by Professor Penelope Gardner-Chloros, Department of Applied Linguistics and Communication

Bilingualism is one of those funny phenomena where those who experience it cannot understand why it is in any way remarkable, while those who do not find it incomprehensible and amazing. A few decades ago it was thought that being bilingual was a definite mental and educational disadvantage. The pendulum has now swung the other way and many advantages of being bilingual are recognized. These advantages, it seems, go beyond the obvious ones, such as being able to understand and relate to other cultures more easily. For example, there is evidence that bilingual children are more creative in specific tasks than their monolingual peers.

You may also have read an article in the press last week about how people who speak several languages recover better from strokes then monolinguals. A year or so ago, there were other articles saying that bilinguals suffering from Alzheimer’s showed symptoms on average 4 to 5 years later than people who only spoke one language. These hidden brain benefits are a relatively new discovery. So at this early stage, what should we make of this research? Academic research very rarely ‘proves’ things beyond the shadow of a doubt, and this area is no exception. The experimental conditions are notoriously difficult to control: ideally, you would need to find sets of monolinguals and bilinguals who learned or use their languages in different ways, but who later suffer the same brain problems and can therefore be compared.

Research on the effects of bilingualism on the brain is ongoing, and there is no clear agreement yet as to what causes the observed effects. If being bilingual does indeed strengthen certain brain functions, then how bilingual do you have to be to gain these benefits? Do you have to be bilingual from birth? Do you have to live in a bilingual society, or are the effects the same if you learn a second language at school, or as a student? What if, like many people around the world, you spoke another language in your childhood but no longer use it as an adult or in later life? Will the benefits still continue to operate? Perhaps the hardest question of all is: what is it exactly about being bilingual which causes the positive effects which are reported?

Some recent research suggests that it is possibly not the fact of knowing two languages which has these benefits, but rather the fact of switching between the two which amounts to a kind of mental workout. This finding was music to my ears: my own research is about code switching, the practice of alternating between two or more languages which characterises the speech of many – probably most – bilinguals. Code-switching arises because people interact with speakers who use different languages, for example when they are at home and when they are at work. But many bilinguals also switch languages within the same conversations, with the same interlocutors. You might hear a sentence in a bilingual family such as:

‘And there’s an airport in every country y claro, in America no tienen airports to(do) lo(s) states.’

(And there’s an airport in every country and obviously, in America not all the states have airports.)

(Data collected by Daniel Weston in Gibraltar)

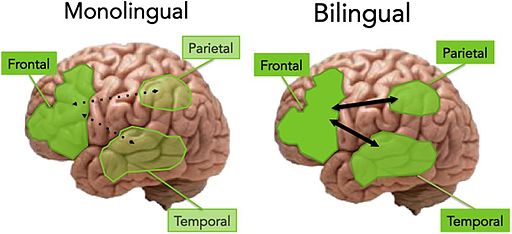

In such conversations, speakers are making rapid choices and decisions between the words in the two languages, and it may be this rapid firing up of different pathways in the brain which constitutes the mental workout. So the actual practice of switching may build strategies for coping with strokes and dementia in later life. Others have pointed out that even when using a single language, bilinguals have to make constant choices; brain scans reveal that both languages are active in the brain even when only one is being spoken. Similar benefits have been reported from playing music or chess, doing crossword puzzles or Sudoku; but apart from professional musicians, these activities are unlikely to be practiced as intensively as talking, so bilinguals in general – and especially habitual code-switchers – probably get the most intensive exposure to this mental workout.

So we cannot say for certain yet what it is about being bilingual that builds the mental muscle, but it is fairly clear that there are benefits attached. You can gain these benefits by learning a new language now. As the saying goes, what’s not to like?

Find out more

It seems that the evidence for faster recovering in bilinguals will continue to amount. I have recently read “Bilingualism and the severity of poststroke aphasia” by A.Paplikar et al., and it seems to be that bilinguals may recover up to two times faster in certain occasions.

I still wish there would be more similar studies of people with non-born multiple-language proficiency, though.